World’s fourth-biggest oil producer can’t keep the lights on

Bloomberg/Dubai

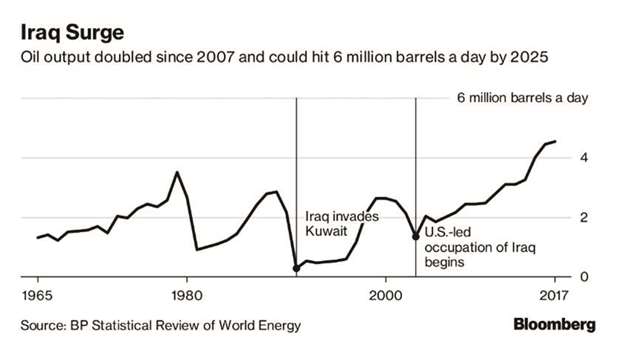

Iraq is fast becoming a global oil powerhouse, gaining stature in Opec after it surpassed Canada this year as the world’s fourth-biggest producer.

But the war-ravaged country has little to show for its feat.

While crude markets are preoccupied with Saudi Arabia’s ability to boost output as impending US sanctions curb Iranian exports, Iraq has quietly increased shipments to Asia, Europe and the Mediterranean region to offset Iran’s missing barrels.

Iraq is producing a record 4.78mn barrels of oil a day, the country’s Oil Minister Jabbar al-Luaibi said on Saturday. Output will rise to 5mn barrels a day in 2019 and 7.5mn in 2024, he said.

Consultant Wood Mackenzie forecasts Iraq could pump 6mn barrels a day by 2025 and that its output is set to grow faster than for all countries but the US over the next six years.

For all its petro-wealth, Iraq lacks steady electricity supplies and has trouble keeping the lights on – and attracting the kinds of investment needed to create jobs and spur local businesses.

“An increase in production is good news, but Iraq still fails to provide basic services like clean water and power to its citizens, including in Basra where most of the oil is extracted,” said Ziad Daoud, Bloomberg’s chief economist in the Middle East.

Most indicators in Iraq beyond oil show little promise. Political tensions continue to simmer due to Baghdad’s stalemate with the country’s semi-autonomous Kurds.

Oil prices have doubled since 2016, bolstering Iraq’s finances, yet the country’s stock index is down 30% over the same period. More than $32bn of foreign direct investment has flowed out of the country over the past five years, according to UN data.

Fifteen years after the US led a military coalition to oust Saddam Hussein’s regime, “people are frustrated that they don’t have 24-hour electricity, that the infrastructure and healthcare are poor,” said Ali al-Mawlawi, head of research at Baghdad-based think tank Al-Bayan Center. “Wealth isn’t trickling down in a fair and equitable way.”

Security improvements and efforts to form a new government are cause for some optimism, al-Mawlawi said in a phone interview. Yet persistent corruption and a cumbersome bureaucracy make “foreign companies apprehensive about investing,” he said.

None of this seems to matter for the oil industry in Iraq, the second-biggest member of the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries after Saudi Arabia.

Oil majors like Exxon Mobil Corp, Total SA, Lukoil PJSC and Gazprom PJSC sat out the latest auction for Iraq’s oil and gas blocks in April, but smaller companies from the United Arab Emirates and China succeeded in securing contracts.

International oil companies are responsible for two-thirds of Iraq’s current production, and their capital and technology are crucial to maintaining and raising output, said Ian Thom, Wood Mackenzie’s principal analyst for Middle East upstream.

As long as the government keeps paying foreign oil companies in full and on time, producers can extract reasonable returns from Iraq’s low-cost fields, even if crude drops to $30 a barrel, Thom said. Brent crude, the global benchmark, has traded at an average of more than $73 this year.

“Iraq will not struggle to find foreign investors to grow its oil sector,” Daoud said. “The challenge is to attract capital and expertise to benefit the broader economy.”