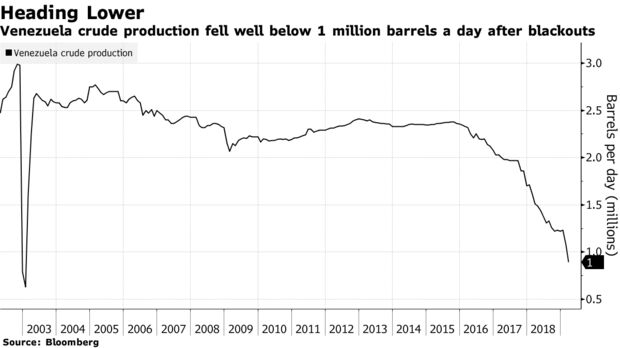

Venezuela Blackouts Cut Oil Output by Half During March

Power failures that plunged Venezuela into darkness for much of March also briefly slashed the country’s crude production by half, according to people familiar with the situation.

Rolling blackouts across much of the country that started on March 7 paralyzed most of the country’s oil wells and rigs, which have slowly come back online. Oil output averaged less than 600,000 barrels a day during the blackouts, the people said, who asked not to be identified because the information isn’t public. For the full month, daily production was 890,000 barrels, according to a Bloomberg survey of officials, analysts and ship-tracking data.

The loss of production due to the blackouts deals another blow to Venezuela’s already-crippled oil industry, already reeling from years of mismanagement and U.S. sanctions that removed its biggest customer. The nation’s crude output, one of the few sources of cash for Nicolas Maduro’s regime, has tumbled by two-thirds since before PDVSA workers went on strike in December 2002.

Near the Orinoco basin in the East, where four out of every five barrels is pumped, heavy tar-like oil has begun to clog pipelines and tanks after the heating system lost power, according to Wills Rangel, a former PDVSA board director and president of the United Workers Federation of Oil, Gas and Related Derivatives of Venezuela. Cleaning or removing the pipes could take months, he said.

“Damage caused by the blackouts at the Orinoco Belt oil fields is substantial,” Rangel said in an interview.

Production Drop

Because of the blow to Orinoco Belt production, a huge drop will be reflected in the March numbers Venezuela will report to OPEC, Rangel said. During the blackouts, production was down to a level similar to Venezuela’s January 2003 reported production to OPEC, which plunged after the PDVSA strike against then-president Hugo Chavez.

The Orinoco Belt area hasn’t recovered fully from the electricity blow and is currently producing about 300,000 barrels a day, he said.

While pumping oil from fields in the Orinoco Belt requires some electricity, the bigger power demand comes from the upgraders — facilities that convert the extra-heavy oil to more commercial blends — located some 300 kilometers away in the north near the coast. The country’s four upgraders are still working to restart.

“If PDVSA restores power at full to all its four upgraders, jointly owned by Chevron, Total, Equinor and Rosneft, it can have an impact on the national grid,” Rangel said.

Upgraders will only have total power once the state run utility allows it, Rangel said. The flow of electricity from the national grid needs to be stabilized before it can bring power back to other high-demand services such Caracas’s subway and water pumping systems. In the fields, oil wells and pumps are expected to be connected under a government-ordered power rationing plan that’s in effect.

— With assistance by Lucia Kassai