Road Map Can Help Coastal Countries Tap Offshore Resources

WASHINGTON, D.C.: A new book by energy expert Roudi Baroudi highlights often overlooked mechanisms that could defuse tensions and help unlock billions of dollars’ worth of oil and gas.

“Maritime Disputes in the Eastern Mediterranean: the Way Forward” – distributed by Brookings Institution Press – outlines the extensive legal and diplomatic framework available to countries looking to resolve contested borders at sea. In it, Baroudi reviews the emergence and (growing) influence of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), whose rules and standards have become the basis for virtually all maritime negotiations and agreements. He also explains how recent advances in science and technology, in particular precision mapping, have expanded the impact of UNCLOS guidelines by taking the guesswork out of any dispute-resolution process based on them.

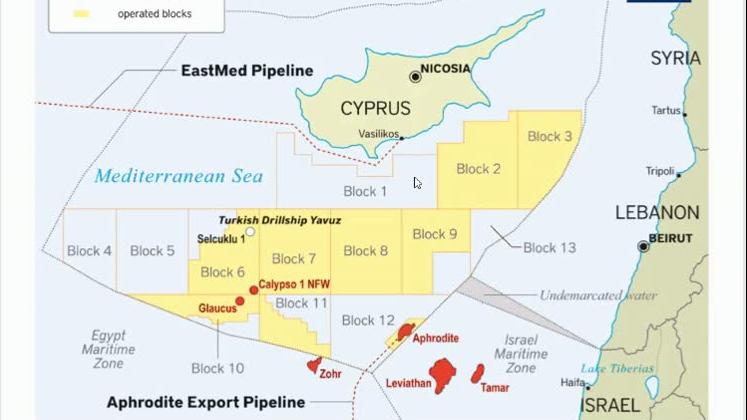

As the title suggests, much of the study centers on the Eastern Mediterranean, where recent oil and gas discoveries have underlined the fact that most of the region’s maritime boundaries remain unresolved. The resulting uncertainty not only slows development of the resources in question (and reinvestment of the proceeds to address poverty and other societal challenges), but also increases the risk of one or more shooting wars. Baroudi notes, however, that just as such problems and their consequences exist around the globe, so might their fair and equitable resolution in one region work to restore faith in multilateralism for peoples and their leaders in all regions.

Were the countries of the Eastern Mediterranean to agree under UNCLOS rules to settle their differences fairly and equitably, he writes, “it would give a chance to demonstrate that the post-World War II architecture of collective security remains not merely a viable approach but also a vital one … It would show the entire world that no obstacles are so great, no enmity so ingrained, and no memories so bitter that they cannot be overcome by following the basic rules to which all UN member states have subscribed by joining it: the responsibility to settle disputes without violence or the threat thereof.”

Baroudi’s work offers both general and specific reminders that levers exist which can level the diplomatic playing field, a useful contribution at a time when the entire concept of multilateralism is under assault from some of the very capitals that once championed its creation. In addition, it is written in an engaging style that makes several disciplines – from history and geography to law and cartography – accessible and interesting to everyone from academics and policymakers to engineers and the general public.

Baroudi’s background consists of more than four decades in the energy sector, during which time he has helped design policy for companies, governments, and multilateral institutions, including the United Nations, the European Commission, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Bank. His areas of expertise range from oil and gas, petrochemicals, power, energy security, and energy-sector reform to environmental impacts and protections, carbon trading, privatization, and infrastructure. He currently serves as CEO of Energy and Environment Holding, an independent consultancy based in Doha, Qatar.

The book has been distilled from years of Baroudi’s personal research, analysis, and advocacy, with editing by Debra L. Cagan (Distinguished Energy Fellow, Transatlantic Leadership Network) and Sasha Toperich (Senior Executive Vice President, Transatlantic Leadership Network).

“Maritime Disputes in the Eastern Mediterranean: the Way Forward” is published by the Transatlantic Leadership Network (TLN), an international association of practitioners, private sector leaders, and policy analysts working to ensure that US-EU relations keep pace with a rapidly globalizing world. Distribution has been entrusted to Brookings Institution Press, founded in 1916 as an outlet for research by scholars associated with the Brookings Institution, widely regarded as the most respected think-tank in the United States.

The TLN hosted a webinar on Thursday to launch the e-book version, with guests and participants joining via Zoom from cities around the world. Following introductory remarks by Cagan and former US Ambassador John B. Craig, a lively discussion took place with a panel featuring Baroudi and two very relevant representatives from the US State Department – Jonathan Moore (Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary, Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs), Kurt Donnelly (Deputy Assistant Secretary for Energy Diplomacy, Bureau of Energy Resources) and Dr. Charles Ellinas (Senior Fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Global Energy Center)

Prior to the launch event, the book had garnered advance praise from key observers, including:

Douglas Hengel, Professional Lecturer in Energy, Resources and Environment Program, Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies, Senior Fellow at German Marshall Fund of the United States, and former State Department official: “In this thoughtful and well-argued book, Roudi Baroudi provides a framework … guiding us down a path to an equitable and peaceful resolution … The countries of the region, as well as the United States and the European Union, should embrace Baroudi’s approach …”

Andrew Novo, Associate Professor of Strategic Studies, National Defense University: “… A balanced, innovative and positive message that can provide progress for a series of apparently insoluble problems. Using international law, highly detailed geo-data, and compelling economic logic, Baroudi makes a powerful case for compromise … if only the opposing sides will listen.”