Thus far attempts to resolve the dispute have been unsuccessful, but while the challenge is clearly a difficult one, the situation is far from irretrievable if the parties practice restraint and resolve to settle their differences via diplomacy and dialogue.

BEIRUT: Tensions between Lebanon and Israel are flaring once again, this time over the demarcation of their maritime border and, therefore, the rightful ownership of offshore oil and gas deposits.

Thus far attempts to resolve the dispute have been unsuccessful, but while the challenge is clearly a difficult one, the situation is far from irretrievable if the parties practice restraint and resolve to settle their differences via diplomacy and dialogue, however indirect.

Diplomatic efforts are complicated by several factors which block many of the usual avenues of dispute resolution. Awareness of these factors and the conditions they impose is a must, especially from the perspective of Lebanon, which will need to walk a virtual tightrope if it is to protect its rights while avoiding both further escalation of the conflict and any erosion of its refusal to recognize Israel.

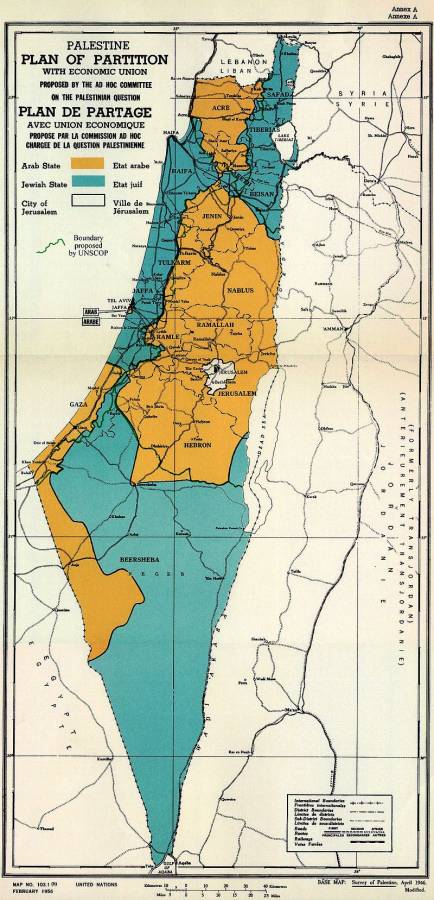

First and foremost, Lebanon and Israel have no diplomatic relations, having remained in a legal state of war since 1948. Lebanon does not recognize Israel, armed non-stated groups have periodically used its territory as a staging area for attempts to liberate Palestine from Israeli occupation, and Israel has attacked, invaded, and/or occupied Lebanon numerous times, the most recent large-scale conflict having taken place in 2006.

The plain fact is that the absence of diplomatic relations is highly problematic for disputes over offshore resources. Most maritime demarcations are set out in treaties between the countries in question, which then serve as legal bases for any necessary adjudication of disputes. Israel and Lebanon have no such treaty, and there is no prospect in the foreseeable future of any kind of reconciliation that would allow them to so much as discuss one.

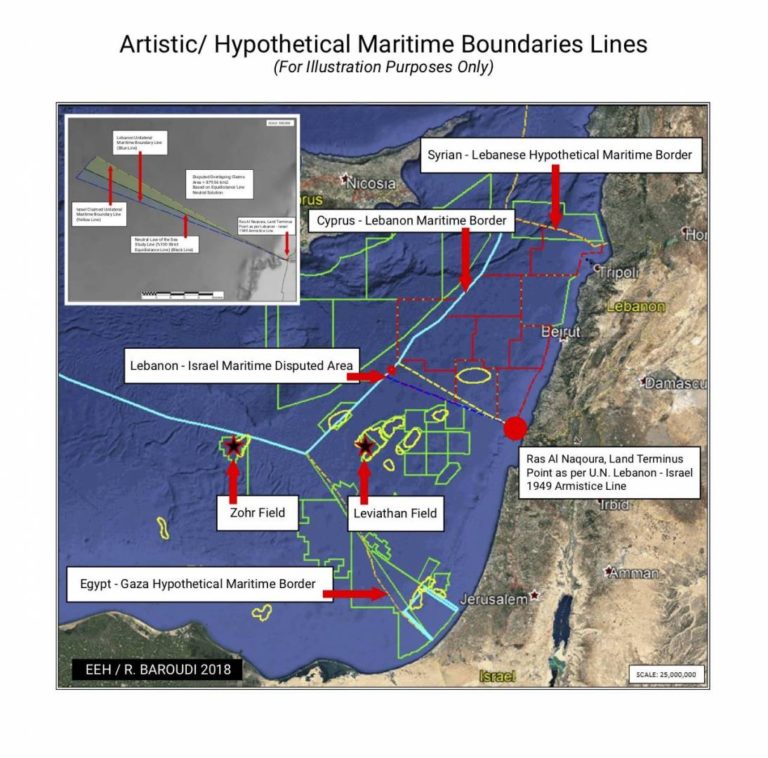

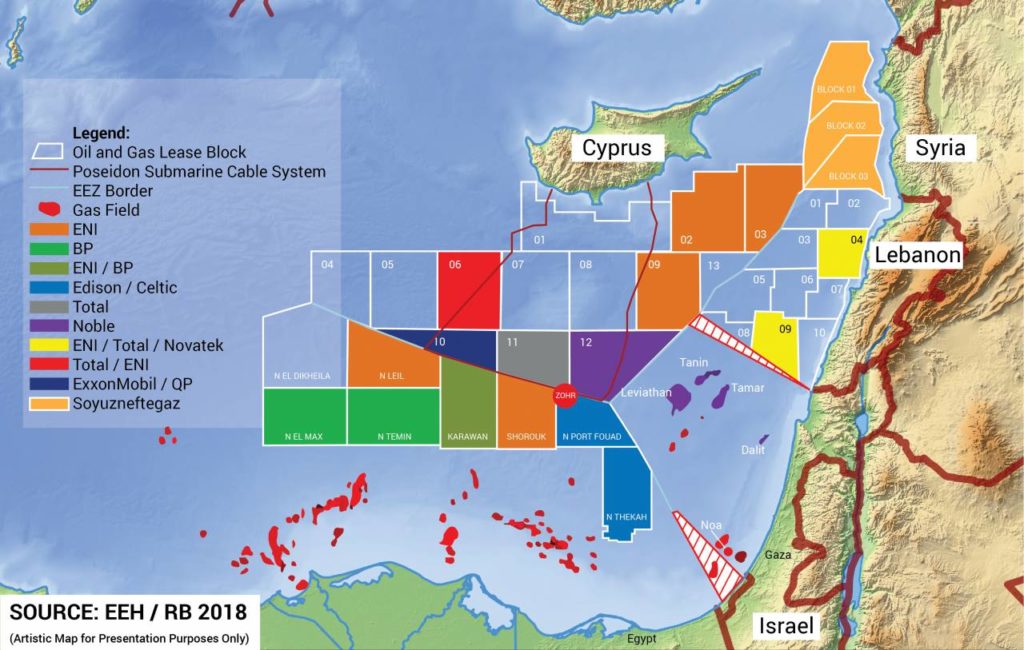

In addition, the two parties appear to disagree not just on the angle at which the southern boundary of Lebanon’s EEZ should extend from the border along the coast, but also on where, precisely, that coastal border lies. Obviously, then, a purely bilateral process is out of the question. And as we shall see below, the absence of relations also throws up obstacles for the conventional use of international institutions.

Second, while Lebanon has signed and ratified the primary international agreement on maritime border demarcation, the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), Israel has not. Accordingly, there is no binding mechanism under which either state can refer the maritime border dispute for resolution without the express agreement of the other. However, since Israel has signed an Exclusive Economic Zone agreement with Cyprus, Lebanon does have options on this level.

One could lodge some form of protest against Cyprus on the basis that its EEZ pact with Israel prejudges Lebanon’s borders, but that seems unlikely and even more inadvisable as it would jeopardize Beirut’s strong relations with Nicosia. Alternatively, Lebanon could invite Cyprus to join it in seeking conciliation under Article 284 of UNCLOS in order to resolve the dispute caused by the Israel-Cyprus EEZ agreement with Israel. Cyprus would have the right to reject such an approach, but it is certainly worth investigating what the Cypriot stance would be. If Cyprus has no objections, this kind of proceeding would demonstrate Lebanon’s commitment to its obligation, under the UN Charter, to seek the peaceful resolution of disputes.

Third, while states regularly refer maritime border disputes for resolution to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) this is typically done by way of a special agreement between the states. This is because, as is, in fact, the case for Lebanon and Israel, very few states have signed up to the compulsory jurisdiction of the ICJ. Unless a state has accepted the compulsory jurisdiction of the ICJ, claims cannot be brought against it before the ICJ without its express agreement in relation to a specific claim.

It is unlikely that either Lebanon or Israel would consider submitting the maritime border dispute to the ICJ for fear that this might set a legal and/or politico-diplomatic precedent. Israel has only ever invoked the ICJ’s jurisdiction once, in 1953, while Lebanon has been involved in two cases before the ICJ, most recently in 1959. Since the ICJ’s 2004 advisory opinion reprimanded Israel for the construction of its wall around the Occupied West Bank, it is unlikely that Israel would consider referring any dispute, let alone one with Lebanon, to the ICJ. Lebanon’s reservations with regard to appointing the ICJ or any third party to resolve the maritime border dispute are two-fold.

First, it has concerns that Israel would seek to condition any agreement to refer the maritime dispute to the ICJ or any other international tribunal provided that Lebanon agrees to subject all border issues for resolution by such body. Second, it worries that any direct agreement with Israel to seek third-party involvement to resolve the dispute may be considered as de facto and de jure recognition of the state of Israel.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, even if the Lebanese-Israeli dispute were to be heard by ITLOS, the ICJ, or some other legal forum (e.g. ad hoc arbitration), the process would have to root its decision(s) in a body of law that would necessarily include what is referred to as “Customary International Law” (CIL) – which neither Israel nor Lebanon accepts in its entirety.

Israel’s policy has long been to stay out of multilateral agreements that presume its acceptance of any international law – customary or otherwise – that might expose its occupation and settlement policies, inter alia, to independent scrutiny and/or sanction. In other words, when Israel “rejects” “accusations” that it’s settling of occupied land violates international law, it does not deny that it commits the acts in question: it simply states its refusal to be bound by a law it does not recognize.

In practice, CIL allows for countries to remain largely outside its reach, but only if they consistently reject its applicability; governments cannot “cherry-pick” which laws to obey based on how they are affected in a particular case. Once you accept CIL in any way, shape, or form, you risk coming under its jurisdiction – a fate that Israel has worked hard to avoid for more than 70 years.

Beirut’s approach is subtly different. Basically, it is happy to enter into multilateral agreements that commit it to meet certain standards, but only provided that doing so neither implies any recognition of Israel nor subjects all of Lebanon’s borders to the judgment of the ICJ, whose verdicts are final and cannot be appealed. That leaves room – not a lot, but some – for the Lebanese state to achieve satisfaction on the offshore issue without sacrificing its general positions vis-à-vis Israel and borders.

In addition, while there are particular elements that make the Lebanon-Israel dispute unique in some ways, the general conditions, in this case, are not unusual. Every coastal state on the planet, for instance, has at least one maritime zone that overlaps with that of another state, and many of these disputes remain unresolved. In the Eastern Mediterranean alone, several pairs of countries have yet to sign bilateral agreements on the boundaries between their respective EEZs, including Cyprus and Turkey, Cyprus and Syria, Greece and Turkey, and Israel and Palestine. Moreover, many of the bilateral maritime treaties that have been reached are opposed by neighboring countries with overlapping zones – as is the case with Lebanon’s opposition to the Israel-Cyprus deal.

What these cases demonstrate is that even when there is plenty of bad blood but no delineation agreement between two states, there is no need to go to war. Quite the contrary, states with sharply opposed interests can and do coexist despite the absence of an agreed maritime boundary. All they have to do is show restraint and practice a modicum of common sense – which is what all states are supposed to do in any event, under their UN Charter obligations.

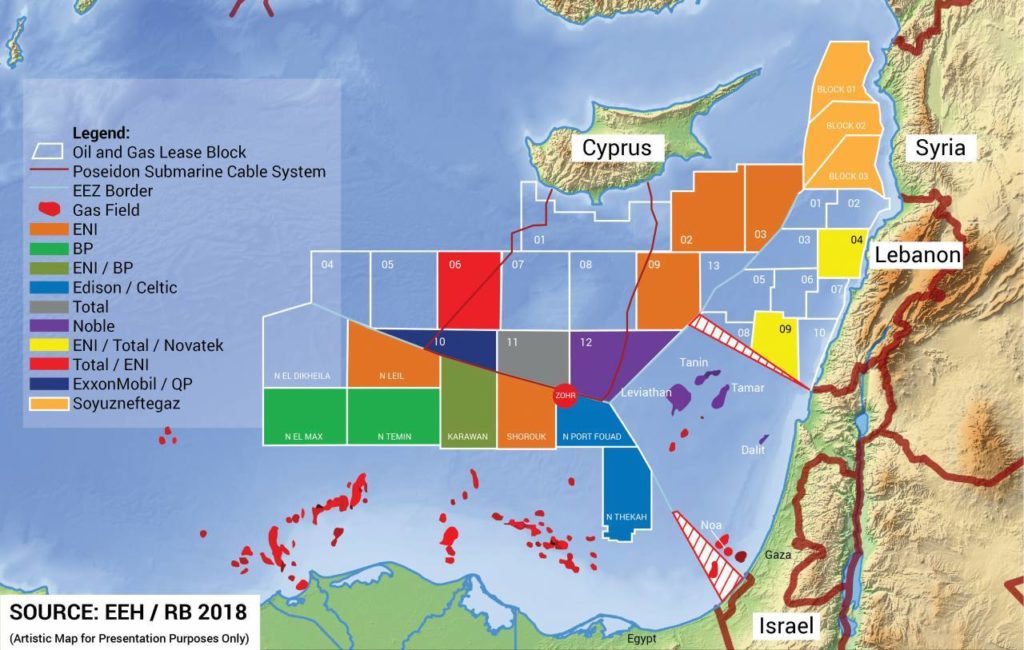

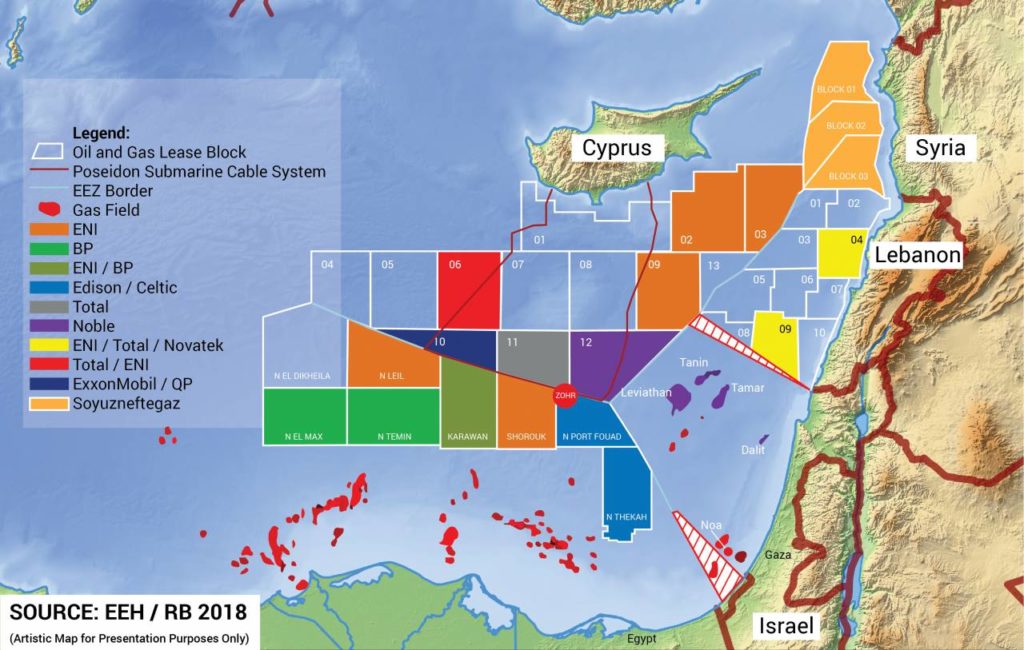

Restraint and (indirect) dialogue should be especially attractive in this case, not least because there is likely to be significant outside support for some kind of solution. In addition to the UN and US efforts, the involvement of France’s TOTAL, Italy’s ENI, and Russia’s Novatek in the region means that each of their respective governments, plus the European Union as a whole, has a vested interest in using their own good offices to mediate an understanding that would, at the very least, open up Lebanon’s Block 9 – thus far its most promising acreage – for exploration.

The real difference between this dispute and others is in the urgency, and that works both ways. It is true, for instance, that the threshold for conflict between Lebanon and Israel is lower than those between other neighbors: threats and even the actual use of force are habitual features of Israeli foreign policy, memories of shooting wars are fresher in Israel and Lebanon than most other places, and the value of the resources means there is plenty to fight over.

On the other hand, those same memories should serve as useful reminders that war is an inherently expensive business, and that any future conflict will extract a heavy cost – human, financial, reputational, etc. – from all concerned. The same goes for the stakes: with so much to gain from drilling and so much to lose from fighting, both countries have a clear interest in removing obstacles so that their respective oil and gas sectors can be developed as quickly as possible.

The important thing for Lebanon is to keep showing good faith and demonstrating commitment to its obligations to uphold peace and security as a signatory to the UN Charter, and thus far it has lived up to this responsibility. While remaining consistent in its refusal to even tacitly acknowledge Israel as a state, Beirut has engaged with two consecutive US envoys who have used a form of shuttle diplomacy to mediate the dispute. It also has made repeated appeals to the UN to help settle the matter. Whatever happens in the future, it is crucial that Lebanon retains this cooperative stance, for it not only protects its legal rights but also helps contain tensions that might otherwise cause Israel to act unilaterally.

One of the levers Lebanon can use to keep demonstrating a constructive position is in UN Security Council Resolution 1701, which ended the 2006 war.

Paragraph 10 of that document gives Lebanon (and Israel) the option to request that the UN Secretary-General proposes the delimitation of the Lebanese-Israeli border. Beirut has indeed asked for the Secretary General’s intervention, but it can help its cause by remaining focused on the issue, particularly the application of UNSCR 1701(10). Again, even if this effort falls short, it cannot but help to have a positive influence on tensions and to further burnish Lebanon’s stature as a responsible state seeking peaceful resolution of a dispute with another party.

Apart from being meticulous about its commitment to peace and security, Lebanon’s leadership also needs to be open and transparent with the general public, whose expectations for the oil and gas sector should be based on facts, not wishes. Educating public opinion will serve not only to address concerns that oil and gas revenues will be squandered by domestic mismanagement, but also reduce fears that Lebanese officials will sacrifice the national interest for the sake of their own personal gain.

The average Lebanese needs to understand that diplomacy often requires give-and-take, and that when it comes to energy especially, there are few zero-sum games: both sides often gain by accepting something less than their maximalist positions – or at least by allowing the time for due process to play out. In this instance, much has been made of the fact that Israel could end up sharing the revenues from any oil- or gasfield that straddles the eventual boundary between the two parties’ respective EEZs. That is certainly possible, but it is also not especially relevant: the same rules of international law apply to straddling fields the world over, including some shared by mutually hostile nations. The same fact also cuts both ways because any agreement requiring Lebanon to share straddling fields first identified on its side of the line would likewise require Israel to do the same. While Lebanon might indeed have to share the potential revenues of fields that have yet to produce (or even be explored), therefore, the same international law principle could well require Israel to share in those of fields that already are producing, possibly including some highly lucrative ones.

Of course, simply convincing Lebanese citizens that a fair settlement can be reached is not the same as promising that one will be reached. Nonetheless, it must be acknowledged that a) the Lebanese case is a strong one; and that b) Israel might well be convinced to accept an arrangement that falls well short of its stated demands.

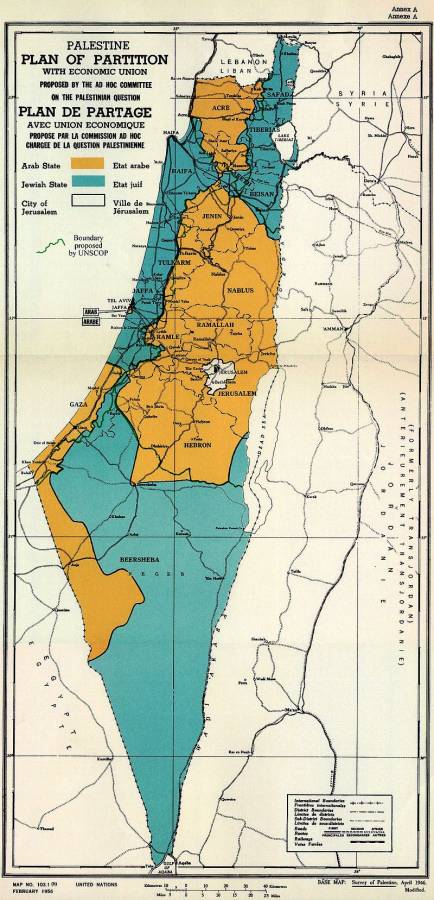

The strength of Lebanon’s position goes all the way back to the 1923 Paulet-Newcomb Agreement, which sets the border between what were then French Mandate Lebanon and British Mandate Palestine, and the 1949 Armistice Agreement, which ended hostilities in the 1948 war between an independent Lebanon and the recently established “state” of Israel. In the words of Israel’s own Ministry of Foreign Affairs (website), the 1949 document “ratified the international border between former Palestine and Lebanon as the armistice line”. This is important, not only because the Paulet-Newcomb pact sets Lebanon’s southern border at Ras Naqoura, an advantageous point (for Lebanon) from which to delimit the two sides’ EEZs, but also because in the absence of bilateral relations and therefore of a substantial record of cross-border trade, diplomacy, or other non-military interaction regarding the border, documents like these carry even more weight than might otherwise be the case.

Other factors also bode well for Lebanon’s short- and long-term legal prospects, including the fact that the part of Block 9 in which TOTAL, ENI, and Novatek are most interested clearly lies well within Lebanon waters – even if one were to accept Israel’s maximalist claims. That leaves plenty of room for at least a short-term compromise that would allow exploration in areas not subject to dispute while leaving more difficult questions for a later time.

The quality of the information Lebanon has submitted to the UN and other interested parties also gives significant weight to its position, and in more than one way. The Lebanese side has used original British Admiralty Hydrographic Charts – widely recognized as the most accurate and authoritative available – as the starting point for the southern boundary of its EEZ, which lends even more credibility to its contentions. And by fortunate coincidence, the Israelis have relied on that very same source for their EEZ agreement with Cyprus (as have the Cypriots for their deal with Egypt).

Even on the issue of accepting CIL, there are signs that Israel may have relaxed its objections. In a March 2017 submission to the UN, the Israeli government said the dispute should be resolved “in accordance with principles of international law”. The missing “the” before “principles” indicates that Israel may well be trying to cherry-pick which elements of CIL it wants to recognize, but the language offers hope that it is ready to be more flexible. Given that there may now be agreement between the parties on certain principles of CIL regarding border delimitation, this could be an opening for a Lebanese submission to the UN Secretary-General to ask that he put forward a proposal.

Even before the 2017 submission, there were already indications of possible Israeli movement. In the December 2010 EEZ agreement between Israel and Cyprus, the preamble refers to both provisions of UNCLOS and principles of international law of the sea applicable to EEZs, even though Israel has never recognized either UNCLOS or international law itself. The same document also allows for review and modification if this is necessary in order to facilitate a future EEZ agreement acceptable to “the three states concerned”, which cannot be interpreted to mean anything but the signatories and Lebanon.

This is not to pretend that the case is cut and dry. On one issue in particular, Israel can be expected to stress that its EEZ Agreement with Cyprus is based on the same maritime starting point that Lebanon used in its own EEZ agreement with Cyprus, which was reached in 2007 but has not been ratified by Parliament. This, however, is basically the only gap in Lebanon’s legal armor in this case, and Beirut has several strong arguments with which to close it: Lebanon could counter a) that in line with the Article 18 of the Vienna Law of the Treaties, which forms part of CIL, the 2007 EEZ agreement is not valid and binding as it was never been ratified by the Lebanese Parliament; b) that point 1 was chosen as the starting point for demarcation of the Cyprus/Lebanese EEZ in order to avoid either implicitly recognizing Israel or giving it a pretext for unilateral action; and c) that the line was never intended to be a permanent one, just an interim solution until a triple point is defined among itself, Cyprus, and Israel.

In short, the average Lebanese needs to know that a well-negotiated deal through third-party mediation or arbitration would mean a far bigger victory for Lebanon than for Israel. The latter, one should keep in mind, is already producing gas from offshore fields, so opening up new ones represents only an incremental gain, making delay less meaningful. Lebanon, by contrast, has yet to start reaping such rewards at all, so the impact of an early start means an instantly massive improvement on the status quo; the sooner it can do so without fear of Israeli aggression, therefore, the better.

There is always the possibility that Israel could seek to short-circuit any diplomatic process in which it feels unable to dictate the outcome. It might not even have to use military force to achieve its ends, only to keep tensions high enough so that no drilling can even take place.

Even a spoiling strategy could cost Israel dearly, however, by further eroding its standing in the international community, alienating key allies, and discouraging investment in its own energy sector. A shooting war would be even worse for Israel, especially since its vulnerable offshore gas facilities would figure to be the highest-value targets of any conflict and would be almost impossible to defend. It is difficult to imagine how any combination of Israeli political and military objectives in Lebanon could justify losing these facilities, which constitute one of the Israeli government’s most productive cash cows.

Once again, there are signs that Israeli officials have performed similar calculations. Most conspicuous has been the absence of Israeli drilling activity in the disputed areas: no licenses have been issued for any of the Israeli blocks that extend into waters claimed by Lebanon. At least for now, and notwithstanding some of the more strident voices, most of Israel’s leadership appears willing to take a wait-and-see approach.

To keep expectations in line with realities, then, Lebanese leaders need to be mindful of what they say in public. While being as transparent as they can for domestic purposes, they also must be politically astute to avoid compromising Beirut’s negotiation position, sending mixed signals, and/or closing diplomatic doors. Measured rhetoric is not a common feature of the Lebanese political arena, but the country does have a first-rate diplomatic service, so perhaps some resources could be invested in a program of regular briefings seminars – for the president, prime minister, speaker, all Cabinet ministers and MPs, and relevant senior civil servants – on how to avoid such missteps, whether at a press conference or a gala dinner.

Apart from maintaining a united front and keeping the public informed, the other priority must be to leave no stone unturned in the search for a peaceful solution. This means that in addition to the US and UN avenues, Beirut would do well to enlist other participants as well, starting with the home countries (France, Italy, and Russia) of the companies forming the consortium that won the rights to Block 9. Then there is the European Commission, which knows full well that all of its member-states stand to benefit from the development of an East Mediterranean gas industry, which would diversify the sources of energy imports, improve the security of supply, and even put downward pressure on prices, adding higher living standards and greater economic competitiveness for good measure.

All of these players could potentially help mediate a formula that works for all concerned, but nothing is more important than reanimating and extending the US mediation role. Whatever one thinks of Washington’s credibility as an honest broker in the Middle East, no other actor has its capacity to influence Israeli decision-making – and so to create sufficient time and space for diplomatic efforts to mature.

Roudi Baroudi is the CEO of Energy and Environment Holding, an independent consultancy based in Doha, and a veteran of more than three decades in the energy business.