EMIR IN GREECE AND CYPRUS

Political 04.06.24

Interview by ALEXIA TASOULI

DIPLOMATIC CORRESPONDENT

POLITICAL.GR NEWSPAPER

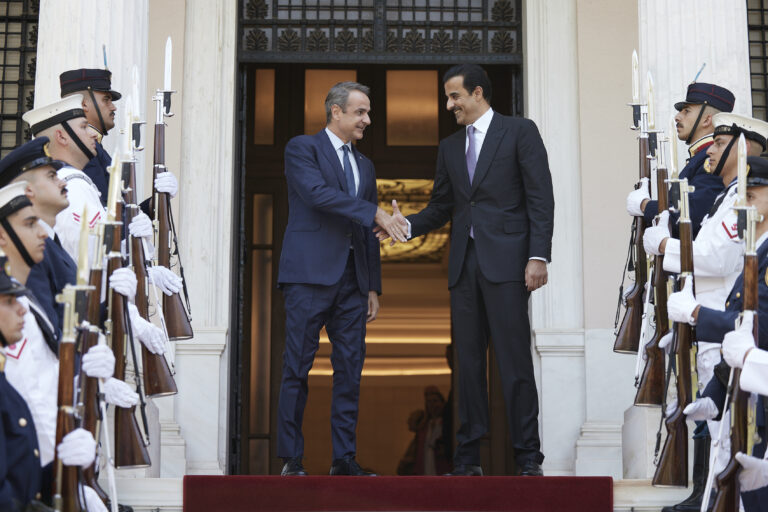

Athens, Friday 31st of May 2024: Qatar’s Emir Sheikh Tamim Bin Hamad AlThani paid official visits to Cyprus and Greece this week, meeting with senior officials from both countries as part of efforts to expand cooperation. International energy expert Roudi Baroudi, CEO of Dohabased independent consultancy Energy and Environment Holding, sat down to answer a few questions about the outcome and significance of the emir’s mission.

Question: Overall, how successful were HH the emir’s visits to Greece and Cyprus?

Answer: Both visits appear to have been very fruitful. HH the emir and his delegation held constructive talks with their counterparts in both countries, and all sides came away with clearer understandings of where the already strong relationships should go next, and how they can get there. Several important first steps were taken toward identifying likely areas for further cooperation, and now both sides have the information they need to come up with proposals for the next steps on several fronts.

Q: From your perspective, what are the main takeaways from HH the emir’s trip?

A: There are several elements at play here, multiple processes unfolding according to their own timelines, but all interrelated in some ways. The first thing to consider is that both visits constitute reaffirmations of Qatar’s traditional diplomatic strategy, much of which revolves around having stable and friendly relations with as many counterparts as possible. That might sound a little basic, but it’s really not: many governments “pick sides” in various international disputes, which often amounts to letting other countries decide your foreign policy for you. By contrast, the Qatari model seeks instead to be on good terms with all sides in most disputes, and the value of that approach has been on display for years: Doha has successfully used its good offices as a mediator in the past, and more recently it has done the same for ceasefire talks and other negotiations between Israel and Hamas.

This same philosophy also informs Qatar’s stances in the Mediterranean, where it looks for the warmest possible relations with Greece and Cyprus while simultaneously maintaining close ties with Türkiye, with which both Athens and Nicosia have been at odds for decades. I should mention, too, that Cyprus follows a similar path, maintaining friendly relations with both Israel and Lebanon, for example.

Both Cyprus and Greece also would like to play central roles in the development and buildout of facilities aimed at carrying energy to the European mainland. This is a core part of their respective plans to grow and develop their respective economies, and the necessary investment and expertise will require strong partnerships.

Q: So how do these priorities tie in with the emir’s visit?

A: In several ways, really. First, HH the emir’s goodwill visit is a reconnection: the COVID pandemic threw a lot of international issues into hibernation as governments everywhere spent a lot of time looking inward for several years. By visiting now, he’s demonstrating in general that he values Qatar’s relationships with both Cyprus and Greece. The reengagement also bodes well for particulars, and there are several opportunities for cooperation because the parties can help one another. Both Greece and Cyprus want to be part of plans to open new channels for natural gas into Europe, whether it’s Eastern Mediterranean gas or from further afield. For this they could find no better partner than Qatar, which, in addition to its own worldleading LNG industry, has also been acquiring stakes in energy assets around the world. But both countries also want investment in other sectors, too, and once again, both the Qatar Investment Authority, the country’s sovereign fund, and various private investors are on the hunt for moneymaking ventures.

Q: What does the emir’s trip mean for Greece, in particular?

A: To me the time looks ripe for more cooperation. The period since 20072008 has been very difficult, but the current government under Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis has done wonders, not just to stabilize the Greek economy and restore hope to the population, but also to help Greece regain its rightful place at the European table. The country is now looking to build on this foundation by fully embracing cuttingedge sectors like digital connectivity and cleantech, but also by reinvigorating its traditional shipping expertise by becoming a major logistics center and by getting more out if its hospitality sector, too. The long recession is over, and some asset classes look very attractive to Qatari investors – and others, as well – especially given the stronger, cleaner governance and leadership on which Mitsotakis has built his reputation.

Q: What about Cyprus?

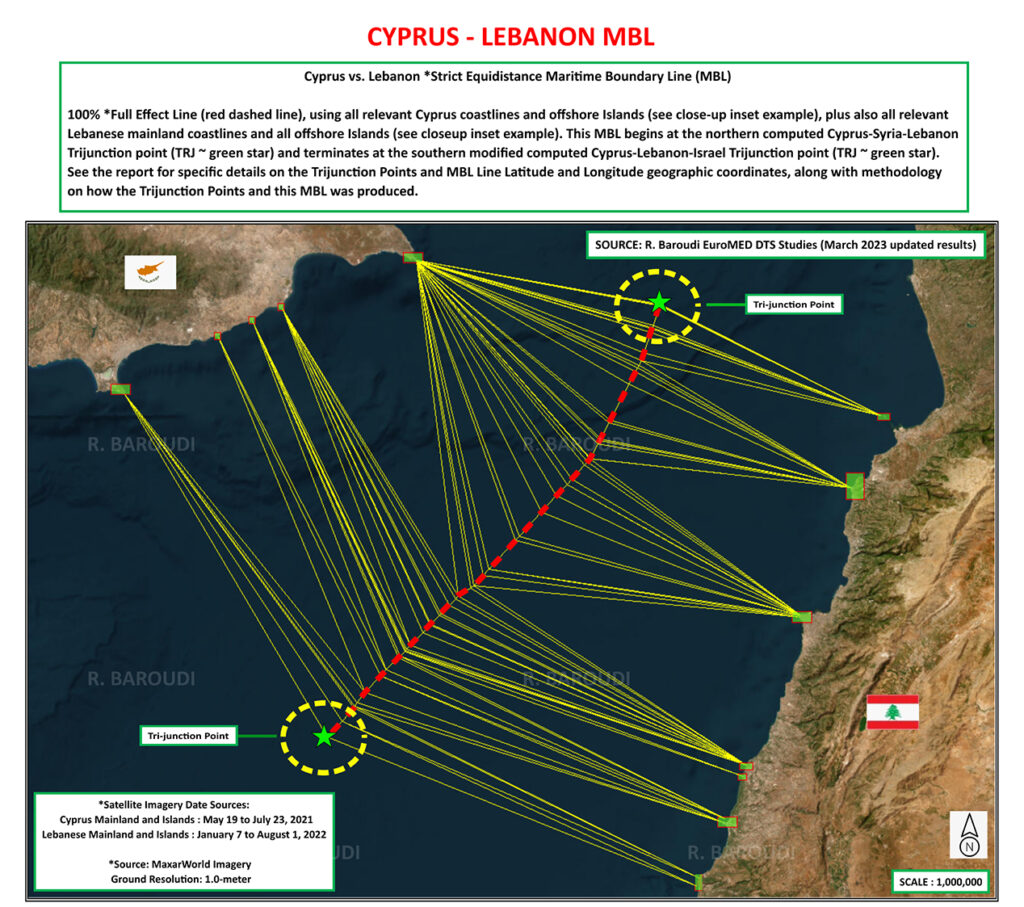

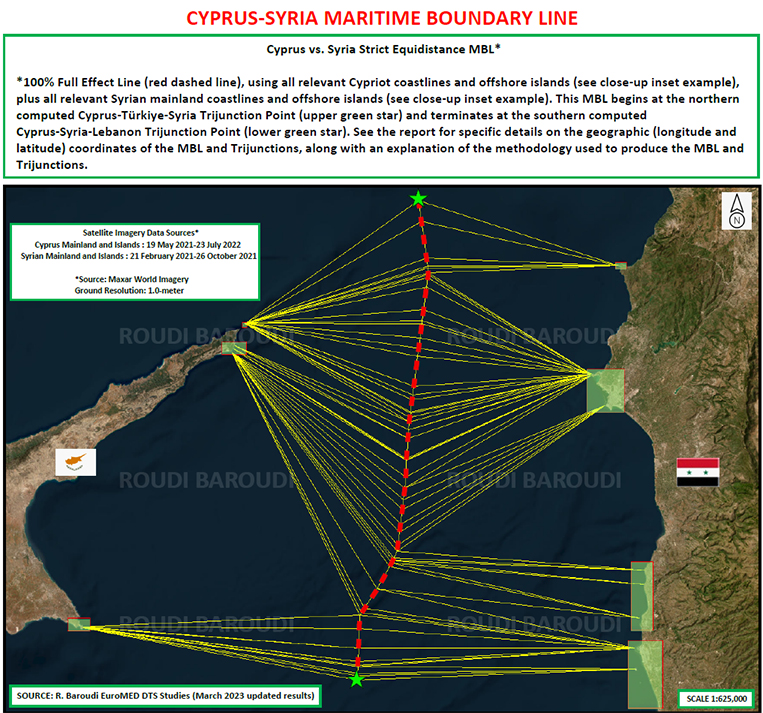

A: Another European land of opportunity. All other things being equal, if the world operated according to logic instead of politics, Cyprus would already be a major energy hub. Its location makes it the ideal base for the Eastern Med’s burgeoning offshore gas industry, which also includes strategic ports, telecoms, and other support services. Many analysts see real potential in several sectors, including ports, banking, and a host of technologies. The increased economic activity will also introduce more people to the beaches and other attractions that make the island’s tourism industry so popular. Another ingredient is leadership: President Nikos Christodoulides has been in office for less than a year, but the former diplomat and foreign minister has already shown himself to be both a highly competent Head of State and a stern defender of his country’s economic development & interests.

And all this is not to mention the shipping of the gas itself, for Cyprus is not just part of the European Union: it is also very much an East Mediterranean country, so it stands to reason that it should become a gateway through which some of the world’s newest gas producers can sell their wares into the world’s largest gas market. Whether it’s a pipeline to Greece, an LNG plant to supply customers in Asia and East Africa, or both, it’s a nobrainer that Cyprus is the place to start the journey. To me, this is Cyprus’ destiny, and if it’s further Qatari investment that makes it happen, so much the better. Remember, too, that QatarEnergy is already involved in Cyprus’ gas industry, partnering with ExxonMobil to explore two offshore blocks. The Qataris know the LNG business like no one else, and their robust & steady reliability as partners is unchallenged: in 20172021, despite an illegal blockade imposed by some of their neighbors, they continued to process and ship at the highest rates to keep supplying LNG to all of their customers around the world, helping to calm world markets during a very vulnerable period.

“Baroudi, left, with Mitsotakis at the 2019 EUArab World Summit in Athens, before the latter became Greece’s prime minister. According to Baroudi, Mitsotakis has done much to speed his country’s recovery.”

Finally, the role played by Qatar and its leaders has captured the attention of the international community due to the wise policies of the Ruler of the Gulf state. His efforts have been lauded and appreciated by East and West alike, ranging from visits of goodwill by the Emir to regional countries, to forging relations based on mutual respect and cooperation. It also has been noted that visits by the Emir tend to manifest high levels of support in mediation, bringing peace, providing materials or otherwise, as and when needed.

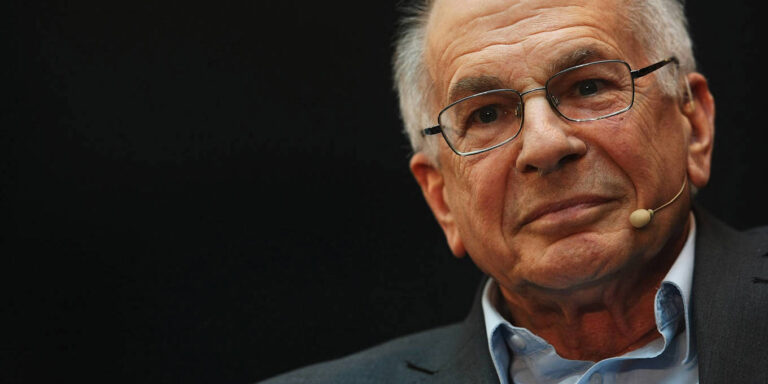

CAMBRIDGE – The recent passing of psychologist and Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman is an apt moment to reflect on his invaluable contribution to the field of behavioral economics. While Alexander Pope’s famous assertion that “to err is human” dates back to 1711, it was the pioneering work of Kahneman and his late co-author and friend Amos Tversky in the 1970s and early 1980s that finally persuaded economists to recognize that people often make mistakes.

When I received a fellowship at Stanford University’s Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences (CASBS) four years ago, it was this fundamental breakthrough that motivated me to choose the office – or “study” (to use CASBS terminology) – that Kahneman occupied during his year at the Center in 1977-78. It seemed like the ideal setting to explore Kahneman’s three major economic contributions, which challenged economic theory’s apocryphal “rational actor” by introducing an element of psychological realism into the discipline.

Kahneman’s first major contribution was his and Tversky’s groundbreaking 1974 study on judgment and uncertainty, which introduced the idea that “biases” and “heuristics,” or rules of thumb, influence our decision-making. Instead of thoroughly analyzing each decision, they found, people tend to rely on mental shortcuts. For example, we may rely on stereotypes (known as the “representativeness heuristic”), be overly influenced by recent experiences (the “availability heuristic”), or use the first piece of information we receive as a reference point (the “anchor effect”).

Second, Kahneman and Tversky’s work on “prospect theory,” which they published in 1979, critiqued expected utility theory as a model of decision-making under risk. Drawing on the “certainty effect,” Kahneman and Tversky argued that humans are psychologically more affected by losses than gains. The perceived loss from misplacing a $20 note, for example, would outweigh the perceived gain from finding a $20 note on the sidewalk, leading to “loss aversion.”

This insight is also at the core of the “framing effect.” The theory, developed while Kahneman was a fellow at CASBS and Tversky was a visiting professor at Stanford, posits that the way information is presented – whether as a loss or a gain – significantly influences the decision-making process, even when what is framed as a loss or gain has the same value.

Lastly, there is Kahneman’s popular masterpiece, the bestselling Thinking, Fast and Slow. Published in 2011 and offering a lifetime’s worth of insights, the book introduced the general public to two stylized modes of human decision-making: the “quick,” instinctive, emotional mode that Kahneman called System 1, and the “slower,” deliberative, or logical mode, which he called System 2. Humans, he showed, are prone to abandoning logic in favor of emotional impulses.

Kahneman received the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2002, despite, as he jokingly remarked, having never taken a single economics course. Nevertheless, his scholarship laid the groundwork for an entirely new field of economic research – and it had all begun in Study 6.

In particular, Kahneman’s work had a profound impact on University of Chicago economist Richard Thaler, who went on to become a Nobel laureate himself. As an assistant professor, Thaler managed to “finagle” a visiting appointment at the National Bureau of Economic Research, whose offices were located down the hill from CASBS, enabling him to connect with Kahneman and Tversky.

In 1998, Thaler co-authored a seminal paper with Cass Sunstein and Christine Jolls, introducing the concept of “bounds” on reason, willpower, and self-interest, and highlighting human limitations that rational-actor models had overlooked. By the time he received the Nobel Prize in 2017, Thaler had systematically documented “anomalies” in human behavior that conventional economics struggled to explain and conducted highly influential research (with Sunstein) on “choice architectures,” popularizing the idea that subtle design changes (“nudges”) can influence human behavior.

But as I gazed at the sweeping views of Palo Alto and the San Francisco Peninsula from the office window at CASBS, the birthplace of behavioral economics, I could not help but wonder whether Kahneman, despite his famously gentle nature, had perhaps been too critical of human decision-making. Are all deviations from “pure” economic logic necessarily “irrational”? Is our inability to align with the idealized model of economic analysis, coupled with our inevitable – albeit predictable – irrationality, really an inherent weakness? And is our tendency to rely on emotions rather than reason a fatal flaw, and if so, could our susceptibility to instinct ultimately lead to our downfall?

I wish I could ask Kahneman these questions. During my time there in 2020-21, Kahneman, affectionately known as “Danny” to all, was not just what CASBS called a “ghost” of the “study” – a former occupant who had been a major influence on my work – but also, happily, a vibrant, living legend who had enthusiastically invited me to discuss these very issues in person. Looking back, I regret my “planning fallacy” in not taking him up on his offer to deepen our conversation sooner – a sentiment shared by both my System 1 and System 2 modes. If “to err is human,” Danny taught me a poignant final lesson in human error.