UN ENVOYÉ très spécial

UN ENVOYÉ très spécial

Dans la poudrière du Golfe où la guerre couve entre le Qatar et l’Arabie saoudite, Emmanuel Macron s’est trouvé un guide atypique : un diplomate arabophone, pieux et royaliste. SOPHIE DES DÉSERTS a rencontré cet oiseau rare, dont les confidences éclairent quarante ans de relations très particulières.

ILLUSTRATION LAURÉNE IPSUM

SABLES MOUVANTS Mohammed Ben Salman, prince héritier d’Arabie saoudite, et Tamim Al-Thani, émir du Qatar, deux jeunes souverains dont le conflit menace la stabilité du Golfe. En arrière-plan, le regard de Bertrand Besancenot, conseiller diplomatique du gouvernement français.

C’est une curiosité, presque une antiquité en Macronie. Il vient de l’ancien monde, ambassadeur à cravate soyeuse et chevalière, pieux catholique, de droite, engagé pour François Fillon durant la campagne présidentielle. Son patronyme, le même que le facteur gauchiste du NPA, a toujours fait sourire au Quai d’Orsay. Besancenot, Bertrand de son prénom, n’a rien d’un révolutionnaire ; tout juste s’il ne souhaite pas le retour de la monarchie. Le genre de spécimen dont, a priori, ne raffole pas Jupiter.

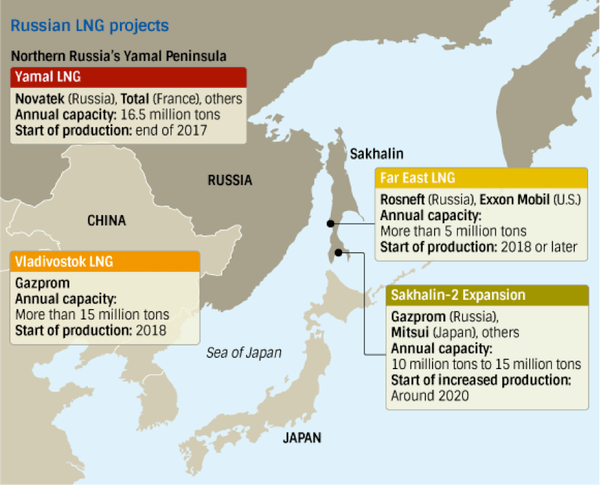

Le diplomate se préparait ainsi à une fin de carrière paisible, au bout d’un couloir poussiéreux du ministère des affaires étrangères. Adieu les postes exaltants au Qatar et en Arabie saoudite où il est resté plus de neuf ans, du jamais vu dans les annales. Il fait un peu gris en France, mais un matin d’août 2017, le téléphone sonne. L’Élysée demande à le voir. À peine élu, Emmanuel Macron a tenté de nouer des liens avec les dirigeants du Golfe qui s’affrontent dans une crise sans précédent. Mohammed Ben Salman, dit « MBS », le nouvel homme fort du royaume saoudien, a 32 ans ; l’émir du Qatar, Tamim Al-Thani, 37. Quelques affinités, au moins générationnelles, pouvaient naître… Le président les a appelés, ainsi que leurs voisins. Mais au Moyen-Orient, tout se tisse lentement. « Time consuming, sans résultat », a déploré Macron devant ses équipes. Il veut au plus vite un envoyé spécial dans la poudrière, quelqu’un susceptible d’éteindre le feu entre l’Arabie saoudite et le Qatar, deux partenaires stratégiques pour la France, grands acheteurs de matériel militaire. On lui souffle qu’il n’y en a qu’un pour cette mission délicate, un diplomate arabophone intimement lié à la famille royale qatarie et tout aussi connecté au cœur du pouvoir saoudien. Il connaît mieux que personne l’histoire et la psyché de ces riches bédouins wahhabites, ce qui les unit, les divise, ce qu’ils pensent secrètement de la France et de ses dirigeants. Besancenot, voilà l’homme qu’il lui faut. « Macron a été droit au but, confie le diplomate. Il avait lu mes notes sur la situation dans le Golfe, la nouvelle donne en Arabie saoudite depuis l’arrivée au pouvoir du roi Salman et de son fils MBS, leur volonté d’isoler le Qatar. C’est un homme politique intelligent, pragmatique, soucieux d’aller vite. » En un quart d’heure, la décision était prise, Besancenot, nommé conseiller diplomatique du gouvernement. Il serait le guide du président dans les sables mouvants du Golfe.

Ne négliger aucun levier, jamais. « La diplomatie Whatsapp fonctionne aussi », observe-t-il, l’œil joueur pointé sur la coupole dorée des Invalides, comme pour faire oublier la modestie de son petit bureau du Quai d’Orsay. Complet gris clair, poignets tenus par des boutons de manchette, Bertrand Besancenot saisit son téléphone et déroule les derniers messages de MBS, le trentenaire enfiévré qui secoue la péninsule arabique. Il l’a connu à 20 ans, beau garçon, courtois, dans l’ombre de son père, Salman, alors gouverneur de Riyad. Une fois intronisé en 2015, à l’âge de 79 ans, le souverain a propulsé son fils ministre de la défense, chef de la maison royale et, enfin, prince héritier. « MBS a toujours été le préféré du roi, souligne Besancenot. Le moins américanisé de ses nombreux enfants, celui qui n’a pas fait d’études aux États-Unis, mais une licence de droit à la King Saud University. » Personne n’avait prédit une telle ascension. MBS est en phase avec la jeunesse d’un pays où deux tiers de la population a moins de 30 ans ; il a compris la soif de changements, devenue impérieuse après la chute des cours du brut. Les déficits se creusent, l’oisiveté subventionnée n’est plus tenable. L’héritier s’est imposé d’une main de fer, réformant à tout-va, l’économie (son plan « Vision 2030 » prévoit des privatisations, des projets futuristes sur la Mer rouge…), le sort des femmes (qui ont désormais le droit de conduire et d’aller au cinéma), sans oublier d’éliminer ses opposants, au prix d’une vague d’arrestations sans précédent, dite « anticorruption », jusque dans sa famille. Même démonstration de force à l’égard des voisins : l’Iran chiite, l’ennemi suprême, menace pour son hégémonie régionale, le Yémen où il poursuit une guerre sanglante et, plus récemment, le Qatar.

Le petit-cousin, jadis docile, s’est pris pour un grand avec sa diplomatie agressive, portée par sa chaîne Al-Jazeera et son soutien aux Frères musulmans, honnis de l’Arabie saoudite. MBS veut le mettre à terre. Le sage prince est devenu guerrier. Besancenot suit de près sa métamorphose. Il a gardé le fil, échange avec lui des textos, dont il ne dévoile que des bribes, à condition de les tenir secrètes. Le devoir de réserve l’oblige. MBS écrit sans manière, direct, cash. Il ne tolère aucune leçon, d’autant qu’il peut compter sur son nouvel ami, Donald Trump, et sur ses voisins, les Émirats arabes unis, le sultanat d’Oman et le Koweït, alignés sur ses positions au sein du conseil de coopération du Golfe (CCG). « La voie est étroite, concède Bertrand Besancenot. Mais il faut répéter ad nauseam que la prolongation de la crise est délétère pour tous, que le monde des affaires déteste plus que tout l’incertitude. »

Pour l’instant, MBS continue sa politique de pression sur Doha, qu’il accuse de tous les maux, et d’abord de soutenir des organisations terroristes, comme Daech. La guerre de l’information s’embrase dans chaque camp, à coups de « fake news », d’e-mails piratés. Le blocus terrestre, maritime, aérien imposé au Qatar par le CCG est maintenu. L’émirat enrage, l’inflation grimpe, des produits manquent, des vaches ont même été importées d’Australie pour éviter une pénurie de lait. Le Qatar cherche de nouveaux appuis en Turquie, en Iran, renforçant encore les foudres de MBS. Besancenot a plaidé pour que Macron le rencontre, en novembre 2017, auretour de l’inauguration du Louvre d’Abou Dhabi. Il fallait au plus vite faire connaissance, engager le dialogue et négocier la libération du premier ministre libanais, Saad Hariri, alors détenu à Riyad. Le président français a effectué un arrêt dans la capitale saoudienne, court mais prometteur. De son côté, le diplomate a entamé une discrète tournée dans le Golfe. « Je leur ai dit à tous : “Faites attention, cette crise profite surtout à l’Iran, avec un risque d’emballement généralisé.” »

MISSI DOMINICI Bertrand Besancenot à Riyad, lors de la signature en 2008 d’un accord entre Veolia et la compagnie saoudienne de distribution d’eau.

« Je visite la suite, il y avait des fleurs de lys peintes dans la cuvette des toilettes. Un Qatari murmure fièrement : “On nous a dit que votre président descendait de Louis XV !” »

BERTRAND BESANCENOT (CONSEILLER DIPLOMATIQUE DU GOUVERNEMENT)

Ventes d’armes et chasses aux faucons

Baptême du feu : Doha, 1978, parce que le nom lui plaisait bien. « Je l’avais entendu à la radio dans une réclame pour la Middle East Airlines, se souvient Besancenot. Doha, c’était doux, exotique. » Il a senti un parfum d’orient, celui de son enfance libanaise dans les années 1960.Le père dirigeait une compagnie d’assurances à Beyrouth. La belle vie, l’école jésuite avec Hervé, son frère jumeau, une bonne adorable qui leur apprit l’arabe et les délices du Chouf ;inoubliables balades dans les montagnes à dos d’âne et ces après-midi de plage où des diplomates en lin devisaient, whisky en main, jusqu’au coucher du soleil. « C’est cette image qui m’a donné envie d’être ambassadeur, songe Besancenot. Si j’avais su… » Il n’a pas pris la voie royale, viré de Sciences Po Paris, comme son jumeau, en raison de leurs chemises à fleurs de lys et de leurs dissertations royalistes, baroques au lendemain de mai 1968. Les deux frères, diplômés de droit, étudièrent aux Langues O’, avant de décrocher le concours du Quai d’Orsay.

À 26 ans, Bertrand atterrit au Qatar, ce confetti d’État récemment libéré du joug anglais. Le voici numéro deux d’une minuscule ambassade. Doha est alors un village de pêcheurs, un seul hôtel, un vieux souk, pas de boutiques de luxe, quelques bateaux tanguent dans la baie où Ieoh Ming Pei, le célèbre architecte, érigera plus tard un somptueux musée d’art islamique. L’émirat somnole encore. Aux commandes, « un notaire de province », le cheikh Khalifa Al-Thani, père de l’ancien émir, Hamad, et grand-père de l’actuel, Tamim. Dans le Golfe, à Riyad notamment, les Al-Thani sont considérés comme des nouveaux riches. Ils ont beau descendre des mêmes tribus bédouines, on les méprise un peu. Le cheikh Khalifa, soucieux de se détacher des Britanniques, se rapproche de la France. Les premiers accords militaires datent de cette époque, les ventes d’armes décollent. Bertrand Besancenot fait la connaissance de Hamad Al-Thani, alors jeune ministre de la défense. Il fréquente les pontes de Lagardère et Dassault qui, plus tard, tenteront de l’embaucher. Initiation aux négociations stratégiques qui demandent tant de politesses, de chasses aux faucons, de pourparlers sans fin, l’apprentissage d’une part essentielle du métier dans la région. En 1980, Besancenot prépare la visite de Valéry Giscard d’Estaing à Doha. « L’émir avait fait refaire pour l’occasion le palais des hôtes de façon grandiose, se souvient-il. On m’a introduit dans la suite présidentielle, la salle de bains en marbre. Il y avait des fleurs de lys azur peintes dans la cuvette des toilettes. » Un Qatari murmure fièrement : « On nous a dit que votre président descendait de Louis XV ! » Giscard salue Besancenot, ébahi de le retrouver alors qu’il jure l’avoir quitté quelques heures plus tôt à Bahreïn… Il s’agissait de son jumeau, Hervé, attaché d’ambassade dans le sultanat voisin. Les inséparables se suivront toute leur carrière, ravis de perpétuer la longue tradition des frères du Quai d’Orsay. Pas à pas, Bertrand Besancenot apprend les us et coutumes des Qataris, les chausse-trappes qu’il faut éviter. Un jour, le cheikh Khalifa le convie sur son trône, entouré de gardes à longs sabres, d’eunuques à plumes, d’oiseaux majestueux. « Vous m’avez rendu service, choisissez ce que vous voulez », dit-il en ordonnant qu’on ouvre sa caverne étincelante de bijoux, de bibelots, de dorures. Le jeune diplomate murmure qu’il ne peut rien accepter. « Mais vous êtes un orientaliste, insiste le souverain. Vous savez que, chez nous, on ne refuse pas un cadeau. Allez prenez ce qu’il y a de plus petit ! » Va pour une montre Omega, seul présent de valeur accepté à ce jour, note Besancenot.

Les Qataris expérimentent déjà la diplomatie du carnet de chèques, offrant à tout-va des valises de cravates, de montres, et même du cash. « Avec tous ces cadeaux, on va être noyé sous les visites de parlementaires », s’inquiète-t-on alors à l’ambassade. Le jeune attaché, lui, observe la moisson des affidés. Il garde ses distances, tout en tissant ses réseaux au bras de son épouse, Maud, une infirmière fine et énergique, fille d’un sénateur gaulliste. Chez les Besancenot, la diplomatie se vit en couple. Ils baptisent leur premier enfant Marie-Doha, joli souvenir du Qatar, avant de s’envoler vers d’autres postes : New York, Bruxelles, puis Genève, à la conférence du désarmement de l’ONU.

DE MÈRE EN FILS La cheikha Moza, récemment reçue à l’Élysée par Brigitte Macron. Son fils, l’émir du Qatar Tamim Al-Thani (page de droite), a eu droit aux honneurs d’Emmanuel Macron.

« Vous êtes un orientaliste. Vous savez que, chez nous, on ne refuse pas un cadeau. Allez, prenez ce qu’il y a de plus petit ! »

KHALIFA AL-THANI À BERTRAND BESANCENOT

« Sept couches de tapis rouge »

Retour dans l’émirat en avril 1998, au poste d’ambassadeur cette fois. Besancenot est reçu à l’Élysée avant son départ. « J’ai un certain nombre de choses à vous dire, s’avance Jacques Chirac. Nous avons le quasi-monopole sur les armes et de gros intérêts à développer dans le secteur gazier. Mais le Qatar est fâché. » La brouille remonte au changement de pouvoir : en 1995, Hamad Al-Thani a profité d’un séjour de son père en Suisse pour le destituer. Il le jugeait frileux, rétrograde, inapte à faire rayonner le Qatar. Il lui en voulait aussi d’avoir toujours préféré son frère, un play-boy, habitué du bar du Fouquet’s, et d’avoir voulu empêcher son mariage avec Moza, cette splendeur, fille d’un opposant. Le vieil émir a tenté de récupérer son trône.Une nuit de février 1996, soutenu par les Saoudiens, il a rassemblé une petite armée au cœur de Doha. Hamad Al-Thani a alors appelé l’ambassadeur de France ; il cherchait de l’aide. Mais personne n’a bougé tandis que les Anglais, eux, dépêchaient discrètement des agents secrets autour du palais et que les Américains mobilisaient leurs troupes. L’émir ne l’a jamais pardonné aux Français. « Chirac m’a dit : “Faites ce qu’il faut, se souvient Bertrand Besancenot. Déroulez sept couches de tapis rouge si ça leur fait plaisir.” Ce petit pays a besoin de beaucoup de considération et d’affection. »

Doha a bien changé, les chantiers pullulent, les immeubles poussent comme des champignons. L’ambassadeur porte ses lettres de créances à Hamad Al-Thani, qui lui parle de la coupe du monde de football et prévient : «La relation franco-qatarie a été détruite par votre prédécesseur.» Peu à peu, les liens se réchauffent. Besancenot découvre « un intellectuel drôle, iconoclaste, ayant horreur du conformisme des dirigeants du Golfe ». Le nouvel émir entend révolutionner son pays. Il s’endette pour exploiter, avec l’aide de Total, l’immense champ gazier partagé avec l’Iran, North Field. Il déploie la chaîne Al-Jazeera pour « donner la parole à la rue arabe », prône un « wahhabisme éclairé », à rebours de la dynastie Saoud qui donne, à ses yeux, une mauvaise image de l’islam. Ça n’empêchera pas le Qatar de soutenir des prêcheurs radicaux, de financer des groupuscules terroristes en Syrie, comme Al-Nosra, une émanation d’Al-Qaida. Double discours, double jeu dont Besancenot n’a jamais été dupe. Il mettra cartes sur table. « Nous avons eu des discussions franches sur le sujet, confie le diplomate. Les Qataris ont le sens des opportunités sans toujours le recul.

Hamad disait : “Il faut se débarrasser du tyran Assad. La bourgeoisie locale prendra le pouvoir.” Je lui répondais : “Regardez ce qu’il s’est passé en France avec l’avènement de la Terreur : chaque révolution porte aussi ses monstres. Vous jouez avec le feu.” » Dans le même temps, l’émir ouvre grand sa porte aux Américains qui s’installent au sud de Doha, dans leur centre de commandement d’Al-Oudeid, à l’endroit même proposé à la France en 1991 pour implanter une base militaire. Besancenot se rend sur l’immense site américain, l’occasion, quelque temps plus tard, d’un autre dialogue avec le souverain.

«Ne pensez-vous pas que vous êtes en train d’installer un ogre dans la région ?

– Rassurez-vous, nous avons le moyen de tout contrôler.

– Permettez-moi d’en douter, votre altesse. Finalement, pourquoi tenez-vous encore à une coopération militaire avec la France ?

« Le Qatar est, avec l’Arabie saoudite, le seul pays à ne pas respecter la liberté de culte. C’est très mauvais pour votre image, et très mauvais pour les affaires. »

BERTRAND BESANCENOT

– Les Américains n’agissent qu’en fonction de leurs intérêts. Ils ont besoin de notre pétrole. Le jour où on ne leur sera plus utiles, ils partiront. Avec vous les Français, c’est différent ; je vois la manière dont vous vous comportez en Afrique… »

L’émir et le diplomate discutent fréquemment, à Doha, au palais ou sur la terrasse de sa villa, au nord de la capitale. Parfois, ils se retrouvent aussi à Paris, comme ce jour de mars 2003, lors de l’enterrement du magnat Jean-Luc Lagardère. Sa veuve, Betty, les a réunis avec leurs femmes, la cheikha Moza et Maud Besancenot. « Vous nous parlez tout le temps de l’amitié franco-qatarie, ose l’ambassadeur. Je vous croirai tout à fait le jour où vous donnerez un fils à Saint-Cyr. » Hamad Al-Thani, qui a envoyé ses premiers garçons à Sandhurst, la célèbre académie militaire anglaise où il a lui même étudié, est surpris. Puis l’idée surgit : pourquoi ne pas confier à la France son fils Joaan, « ce cheval échappé qui ne respecte rien ». « L’armée lui apprendra peut-être la discipline… », souffle-t-il. Les parents qataris insistent : pas de privilège s’il enfreint les règles. Un jour, la cheikha Moza appelle Besancenot : elle veut savoir si l’Aïd est une fête nationale en France. Non, alors pourquoi son fils bulle-t-il à Doha depuis quinze jours ? « Faites-le rapatrier immédiatement », ordonne son altesse. C’est elle le cerveau, la poigne, la femme d’affaires qui pilote aussi l’éducation au Qatar, avec un tropisme pour les universités américaines, au grand dam de l’ambassadeur qui peine à pousser les écoles françaises. Quelques mois plus tard, le prince rebelle est arrêté sur l’autoroute, à 210 km/h, sans permis, au volant de sa Ferrari. Il est loin de Saint-Cyr, au commissariat de Blois. « Alors Joaan, on est en taule ? » le taquine l’ambassadeur. Heureusement, sa sœur, Mayassa, est plus sage. Francophone comme tous les enfants Al-Thani, elle vient en stage à Paris, chez Lagardère, hébergée par les Villepin, et passe des vacances en Vendée, dans la propriété des Besancenot.

La diplomatie devient une affaire de famille. Les Al-Thani reçoivent l’ambassadeur de France et son épouse au mariage de leur fils, Tamim, et aussi sur leur yacht, le Constellation, au large de Cannes, ou dans les terres, sur la terrasse de leur domaine de Mouans-Sartoux. Marie-Doha fête ses 20 ans au palais royal du Qatar. « Bertrand Besancenot a su créer des liens uniques », reconnaît, intrigué, un haut fonctionnaire du Quai d’Orsay. Tout plaît aux souverains du Golfe : son professionnalisme, sa maîtrise de l’arabe, son humour, ses convictions de monarchiste, « attaché à la démocratie », précise-t-il toujours avec malice. Et sa foi catholique ne pose aucun problème, bien au contraire. En terre wahhabite, rien n’est plus inacceptable qu’un homme qui ne croit en rien. « Hamad et moi discutions beaucoup de religion, confesse l’ambassadeur. Je lui disais: “Vous êtes le seul pays, avec l’Arabie saoudite, à ne pas respecter la liberté de culte. C’est très mauvais pour votre image et très mauvais pour les affaires.” » Il convainc ainsi l’émir de recevoir l’évêque d’Abou Dhabi. « Vous vous faites mener en bateau », marmonne en chemin le dignitaire catholique, venu sans apparat. Hamad Al-Thani ressort ravi de l’entretien : « La prochaine fois, vous viendrez avec la ceinture rouge et le crucifix. » Feu vert pour la construction d’une église, financée par des dons, où les catholiques français se recueillentdésormais avec les ouvriers philippins. Pour ce miracle, Benoît XVI décorera Bertrand Besancenot de la grand-croix de l’ordre de saint Grégoire. Mais l’émir est embarrassé; désormais les Britanniques réclament un temple, puis les témoins de Jéhovah s’y mettent. « Les catholiques et les protestants, c’est comme chez vous, les sunnites et les chiites », lui explique Besancenot, qui suggère un « compound » (un quartier sécurisé) réservé aux chrétiens. Le Qatari accepte, désireux de montrer son ouverture, loin de l’intégrisme saoudien.

« La femme est la plus belle création de Dieu. Et vous, vous cachez son visage. »

— BERTRAND BESANCENOT DEVANT UNE ASSEMBLÉE DE RELIGIEUX SAOUDIENS

Coup de sang contre Sarkozy

Une abaya noire. Voici le cadeau de la cheikha Moza à Maud Besancenot, pour affronter l’Arabie saoudite, où son mari est nommé à l’été 2007. « Vous en aurez besoin là-bas », ironise la souveraine du Qatar. On est le 14 juillet. À Paris, les Al-Thani reçoivent les Besancenot dans leur penthouse penché sur les Tuileries, la veille de leur départ pour Riyad. Déjeuner chaleureux, promesse de se revoir, l’ambassadeur reviendra chaque année à Doha. En attendant, l’élection de Nicolas Sarkozy réjouit le clan Al-Thani. Open bar pour les investissements qataris en France, du PSG à Veolia, de Vinci à Accor, immobilier de luxe avec fiscalité avantageuse. Cela vaut bien de soutenir sans compter ce président, pour financer la libération des infirmières bulgares ou la guerre en Libye. Il se murmure même que l’émirat a payé le divorce de Sarkozy. Besancenot n’écoute pas les rumeurs, trop content de se tenir loin des liaisons dangereuses, pendant que ses successeurs à Doha en bavent. L’un d’eux s’est même vu gratifier par Sarkozy d’un « pousse-toi, connard », en public. « Avec le Qatar, les liens ont parfois été un peu passionnels, élude habilement Besancenot. Avec les Saoudiens, la relation est plus sereine, plus mature. »

Au cœur de l’été 2007, l’ambassadeur de France se présente au palais royal de Riyad avec ses lettres de créance. « Nous espèrons que vous ne nous regardez pas avec des yeux de Qataris », lui lancent plusieurs ministres du roi Abdallah. Sourire du diplomate : « Les Qataris sont des amis. Mais on n’est pas toujours d’accord avec ses amis. » Il l’apprend vite : les Saoudiens ne tolèrent pas la moindre allusion au Qatar, deux millions d’habitants, dont trois quarts d’étrangers, un moustique comparé au royaume de La Mecque et ses 32 millions de croyants. « Ils n’ont jamais été colonisés par un État occidental, rappelle le diplomate. Et dans leur esprit, l’unité du pays s’est faite seulement à deux époques : du temps de Mahomet et sous les Saoud, qui règnent depuis le

XVIIIe siècle et sont à l’origine du prodigieux développement économique des années 1970. Ne l’oubliez jamais : ils marchent sur ces deux jambes.» Besancenot voyage d’est en ouest, perce les subtilités de la société tribale, le poids de ces grandes familles, comme les Ben Laden, riches à milliards. Dans sa feuille de route, il y a des paquets de contrats à finaliser, dans le domaine de l’énergie, des transports, de la défense, de la modernisation de la flotte saoudienne à ce TGV a priori sur les rails qui échappera au dernier moment à Alstom. L’ambassadeur s’active, il faut profiter du relâchement des liens avec les États-gravées à son nom, envisage la venue de son chanteur favori, Charles Aznavour, à Riyad (mais les 500 000 euros demandés ne rentraient pas dans le budget de l’ambassade) et pourquoi pas les chevaux de la Garde républicaine.

Il en faut des attentions, car la politique de Sarkozy déroute parfois. À l’été 2008, le vieux roi pique un coup de sang en apprenant la visite de Bachar Al-Assad à Paris, le 14 juillet, sur une suggestion du Qatar. Scandaleux, le dirigeant syrien est soupçonné d’avoir commandité l’assassinat du premier ministre libanais Rafic Hariri. Abdallah fait porter une missive indignée à Sarkozy. Qui fulmine. « Grâce à Bertrand Besancenot, les choses se sont calmées, confie l’ancien secrétaire général de l’Élysée, ClaudeGuéant, alors missionné auprès du roi. Notre ambassadeur avait la confiance totale des Saoudiens. » Il faut slalomer entre les envoyés spéciaux de la Sarkozie, le sulfureux intermédiaire AlexandreDjouhri qu’il s’efforce de tenir à l’écart, Dominique de Villepin qu’on le charge d’introduire auprès du roi en 2011. « En démocratie, vous avez beaucoup de choses surprenantes», s’étonne-t-on au palais, qui cette fois ne donne pas suite.

Besancenot escorte au cœur du pouvoir saoudien les grands patrons, les ministres comme Hervé Morin, ou Christine Lagarde, très appréciée du roi. Avec Bernard Kouchner, c’est plus rude. Le ministre des affaires étrangères se présente en jean, sans cravate, pas rasé. DansUnis, ces alliés désormais plus distants avec Obama. Il se rapproche du ministre du commerce, des affaires étrangères, du tout-puissant vizir Khaled Touijri, alors directeur du cabinet du roi. Abdallah reçoit Besancenot dans ses palais, à Riyad, ou dans le désert. Conversation en arabe, parfois sans interprète. On parle business, sécurité, diplomatie. L’ambassadeur de France a le sens du geste ; il offre au monarque des boules de pétanque la Mercedes saoudienne blindée qui le conduit au palais, il éructe : « Ce mec, qu’est-ce qu’il se paie comme baraque… Et dire qu’on critique Omar Bongo ! » L’ambassadeur avale sa salive, désigne d’un doigt fébrile les micros cachés dans l’habitacle. Devant le roi, Kouchner multiplie les faux pas, donneur de leçons sur la situation en Irak. Et il recommence le soir, lors d’un dîner en faveur de femmes de la haute société saoudienne. À peine si le « french doctor » ne les traite pas d’arriérées : « Vous êtes professeur d’université et on vous empêche de conduire. Comment acceptez-vous ça ? » Une dame lui répond que l’autorisation d’un homme appelé « mahram » (une sorte de tuteur qui peut être le mari, un frère, un oncle) est nécessaire pour tout : sortir, travailler, convoler. « Qu’est-ce qu’ils sont cons, ces musulmans », soupire Kouchner sur le trajet du retour.

Les temps changent avec l’arrivée de François Hollande en 2012. Laurent Fabius est plus subtil et les relations avec le nouveau président sont bonnes. Le roi apprécie son humour. Besancenot aussi : « Vous vous en fichez de ce que je vous dis, hein, puisque vous êtes royaliste », lui glisse Hollande un jour en roulant vers l’aéroport de Riyad. Le chef de l’État mesure à chaque visite combien cet ambassadeur est aimé. Les Saoudiens ne veulent pas le laisser partir. « Tant que je serai vivant, vous resterez, a juré le vieil Abdallah en tapotant sur la main de Besancenot. Vous êtes notre meilleur ambassadeur en France. » Le roi a notamment apprécié l’intervention du diplomate en 2011 devant l’Assemblée nationale. Il l’assurait alors : il n’y aurait pas de printemps arabe en Arabie saoudite. Certains avaient à ce moment-là soupçonné Besancenot de souffrir « du syndrome de Stockholm ». Mais il maintenait ses positions, pas de soulèvement en vue dans un royaume où tout est sous contrôle, avec une classe moyenne aisée, peu de pauvres, pas d’opposition. Au même moment, en Égypte, en Tunisie, les Qataris soufflaient sur les braises en poussant les Frères musulmans à prendre le pouvoir.

Le roi Abdallah est reconnaissant. En 2013, il promet 2,5 milliards d’euros pour l’achat de matériel militaire français à destination du Liban. (Les armes ne seront finalement pas livrées à Beyrouth, désormais jugée sous emprise de Téhéran.) Les autorités du royaume ont confiance en Besancenot, elles ferment les yeux sur les messes du jeudi à la résidence, les fêtes organisées par Maud, défilés de mode caritatifs et autres soirées à thème – vendanges, Caraïbes… – avec cocktails et vins fins. Un jour, l’ambassadeur reçoit une lettre de menace : « Sale porc, je t’ai vu dans ta voiture derrière ton drapeau. Je n’avais pas de couteau mais la prochaine fois… » Sa 607 blindée croise parfois des yeux vengeurs, mais il préfère les ignorer. Et quand la tension monte, notamment après la loi sur la burqa ou l’affaire des caricatures de Charlie Hebdo, le diplomate va au charbon. Il multiplie les rencontres. Le voici un soir à dîner devant une assemblée de barbus en dishdasha. Souvenirs d’explications cocasses sur le concept de laïcité. Il n’a rien oublié : « Je leur ai dit sur tous les tons : “Il faut que vous respectiez notre liberté chez nous, comme nous respectons vos lois dans votre pays.” » Regards noirs et dialogue de sourds. Avant de partir, le diplomate tente de détendre l’atmosphère : « Au fond, nous sommes tous croyants, mais nous n’aimons pas Dieu de la même façon. Regardez, on est d’accord : Dieu a tout créé. » Accord autour de la table. « La femme est bien sa plus belle création, poursuit-il. Nouvel acquiescement. Et vous, vous cachez son visage. » Enfin, quelques sourires percent sous les barbes : « You have the point ! »

SON AMI LE ROI Bertrand Besancenot aux Invalides avec des dignitaires saoudiens lors d’une visite officielle du prince héritier en septembre 2014.

La trahison de Hollande

Dieu, encore et toujours. C’est aussi un sujet avec le roi Abdallah. Besancenot ne l’a pas convaincu d’ouvrir une église, mais au moins peut-il faire venir, en catimini, quelques prêtres. Au crépuscule de sa vie, le roi malade s’est confié : « Beaucoup de gens s’interrogent sur le sens à donner à la vie avec le consumérisme, tout ce que la mondialisation offre, ça ne suffit pas. Nous, les politiques, comme les religieux avons un rôle à jouer. J’apprécie les gens qui, comme vous, pensent qu’il y a quelque chose au-delà. » Abdallah meurt fin janvier 2015 et son demi-frère, Salman, 79 ans, prend sa place. Il manifeste aussitôt sa volonté de garder l’ambassadeur de France, qu’il a connu quand il était gouverneur de Riyad. Besancenot lui a présenté nombre de politiques et de dirigeants. Discrètement, il lui a aussi adressé quelques ardoises de Saoudiens partis sans payer celles d’un palace ou d’une luxueuse boutique en France. «Pour l’image de la maison Saoud… » a maintes fois plaidé Besancenot dans ses courriers. Le jeune prince, MBS, alors chef de la maison royale, a toujours réglé sans commentaires. Il tenait ainsi la liste des mauvais sujets, consignait des preuves dont il se servirait plus tard. L’héritier prend du galon. Début 2015, il reçoit Besancenot pour lui annoncer que le roi entend investir une cinquantaine de milliards dans des projets français. Champagne au Quai d’Orsay. Dans la foulée, François Hollande est convié, début mai 2015, à participer au conseil de coopération du Golfe en tant qu’invité d’honneur. Une première pour un Occidental. Devant tout le monde, le roi Salman demande à Hollande que Besancenot mette en œuvre le plan d’investissements. Lui qui comptait enfin partir comme ambassadeur de France au Saint-Siège… Il accepte la mission à condition de pouvoir rester en Arabie saoudite jusqu’à sa retraite. Hollande le lui promet. Le ciel est clair, Besancenot encourage alors MBS et son père à passer des vacances dans leur propriété de Vallauris, où ils n’ont pas mis les pieds depuis dix ans. Ce serait un beau signe d’amitié.

COUP DE MAIN Bertrand Besancenot et le ministre saoudien de l’intérieur Mohammed Ben Sayef à l’Élysée, pour une rencontre avec François Hollande en 2013.

En juillet 2015, le roi d’Arabie saoudite, vexé, quitte Vallauris avec sa cour. « Les Saoudiens ont parfois du mal à nous comprendre », souffle Besancenot.

Couper l’antenne d’Al-Jazeera

En juillet 2015, le roi débarque ainsi avec sa cour de mille personnes, prêtes à dépenser des millions d’euros chaque jour. Les commerçants se réjouissent, mais la polémique enfle dans la presse : la petite plage en contrebas de la villa royale a été fermée aux vacanciers et il se dit que Salman aurait protesté contre la présence d’une policière. Besancenot s’emploie à dégonfler l’affaire, suggère à Hollande de passer un coup de fil d’apaisement aux Saoudiens. Mais ça ne sert à rien. Le roi, vexé, s’en va. « Les Saoudiens ont parfois du mal à nous comprendre », souffle l’ambassadeur. Lui aussi est humilié. À l’automne 2016, il apprend par hasard la nomination de son remplaçant. C’est fini, il doit quitter le royaume saoudien. Hollande n’a pas tenu promesse.

« Que vaut-il, ce Macron ? » lui demande-t-on depuis Doha et Riyad durant la campagne présidentielle. MBS a pris quelques informations auprès de Jacques Attali, cet habitué du royaume qu’il côtoie depuis des années. Tous les princes du Golfe s’interrogent : le candidat En marche! a promis qu’il n’aurait « aucune complaisance » à leur égard, laissant entendre qu’il reviendrait sur les conventions fiscales. Besancenot connaît peu Macron à qui il a seulement présenté quelques investisseurs saoudiens, à l’époque de Bercy. Lui, il fait campagne pour Fillon, planche sur le programme diplomatique tandis que Marie-Doha, sa fille devenue normalienne, œuvre sur les discours. Chacun ses opinions. À l’époque, les Saoudiens ne sont pas contre un deuxième mandat de Hollande. Les Al-Thani, eux, ont souffert sous son quinquennat, s’estimant victimes d’un « Qatar bashing » exclusivement français qu’ils tentent encore de comprendre. Quelle ingratitude après tous ces millions dépensés, notamment dans les Rafale et autres bâtiments historiques vendus par le Quai d’Orsay. En vérité, les Qataris paient leur proximité avec Sarkozy. Pourtant, jusqu’au bout, ils ont espéré son retour. « Le seul véritable homme d’État », disaient-ils.

Les Qataris ont fait les mauvais choix, même en Amérique où ils ont financé la campagne de Hillary Clinton. Donald Trump n’oublie rien : depuis son élection, il soutient sans réserve l’Arabie saoudite, partenaire historique, y compris pour ses propres affaires (plusieurs princes ont notamment investi dans la tour Trump). Le jeune MBS lui plaît avec son style direct, sa haine de l’Iran, son goût du business. Déjà 380 millions de dollars (300 millions d’euros) de contrats raflés en mai lors d’un premier voyage à Riyad. À ce prix-là, pas de quartier pour le Qatar. En juin, sur Twitter, Trump accuse l’émirat de soutenir « l’extrémisme religieux au plus haut niveau ». Et tant pis si le pays abrite toujours la plus grande base militaire américaine du Golfe. Il met de l’huile sur le feu, légitimant en quelque sorte le blocus. Sa levée est conditionnée à une liste de mesures intenables, comme la fermeture d’Al-Jazeera. Les Qataris, furieux, s’arment jusqu’aux dents et se rapprochent de la Turquie et de l’Iran. Le Koweït, désigné comme médiateur, demande de l’aide à la France. Et Besancenot est appelé par Macron pour démêler ces fils inextricables. Il retrouve ainsi son vieil ami Hamad, et Tamim, ce fils jadis peu porté sur la politique et devenu héros national. En face, le jeune MBS, décidé lui aussi à entrer dans l’histoire. Et Trump qui a osé démettre en un tweet son secrétaire d’État Rex Tillerson, seul partisan d’une ligne sage dans la crise. Il faut garder la foi.

Entre deux tournées dans la péninsule arabique, Besancenot s’est rendu à Washington en février. Il voulait s’assurer que l’administration américaine soutiendrait réellement les efforts de paix. C’est décidé, Macron entend jouer un rôle dans la poudrière du Golfe. Besancenot l’y prépare en coulisses. « Nul n’est besoin d’espérer pour entreprendre », dit-il. Pas mécontent de servir enfin un président qui a tout d’un monarque.

DROIT DE RÉPONSE

Nous avons reçu de Jean-Pierre Mounet, de l’association Interstices, le courrier suivant : « Dans son no 54 de février 2018, Vanity Fair a publié un article consacré à Edwy Plenel, en mettant en cause l’association Interstices dont je suis le coprésident. Je tiens à préciser que notre association n’a rien à voir, ni de près ni de loin, avec la mouvance des Frères musulmans. Pour nous, il est infondé et invraisemblable que M. El Korchi, traducteur en arabe du livre d’Edwy Plenel Pour les musulmans, appartienne à ce mouvement. Comme cela est indiqué sur notre site asso-interstices.fr, nous sommes une association laïque et citoyenne opposée à tous les extrémismes et dont les objectifs statutaires et les activités sont axés sur l’interculturalité, le renforcement des liens franco-marocains et la lutte contre les discriminations, notamment de genre. Je suis profondément choqué que cette association que je copréside soit assimilée à un mouvement considéré comme très loin de la tolérance et des valeurs républicaines et laïques qui nous portent. »

Nous maintenons l’intégralité de nos informations sur les liens entre M. El Korchi et le Qatar. — SOPHIE DES DÉSERTS

VANITY FAIL

Dans la page « table d’addiction » du même numéro, nous avons interverti par erreur les chaussures Roger Vivier et Nicholas Kirkwood, attribué une sandale Clergerie (la marque) à Robert Clergerie (son créateur) tandis que le soulier (fermé) Giorgio Armani n’était clairement pas un escarpin (ouvert) d’Orsay (dépourvu d’ailes de quartier).