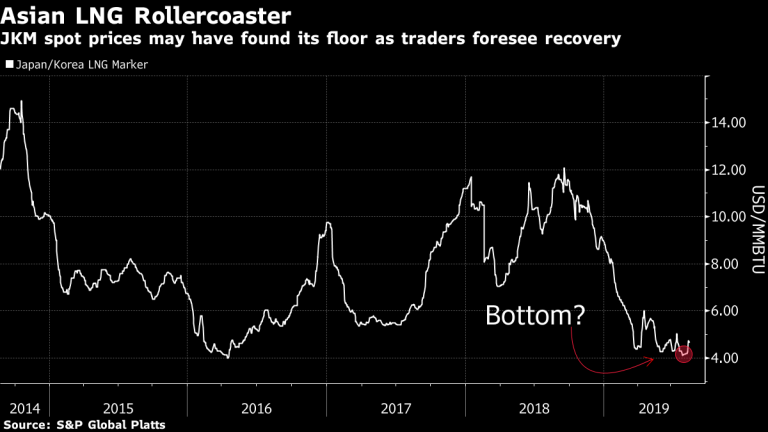

Traders spot opportunity with LNG prices at rock bottom

LONDON (Bloomberg) – After prices plunged to their lowest on record for this time of year, traders say buyers from Japan to India have started to snap up cargoes in anticipation of a pickup in winter demand. Procurement for the colder season is only expected to intensify over what’s left of the summer.

“We have likely reached bottom,” Sanford C. Bernstein & Co analysts including Neil Beveridge said in a report.

The rout can be traced back to last winter, when mild weather dented demand for heating in large parts of the northern hemisphere. To make matters worse for producers, which are adding supply at a record pace, consumption for cooling in the past few months wasn’t very strong either. A market in contango is also pushing some traders to consider storing gas on tankers to sell later at a higher price, a practice that last year began later in autumn.

Another sign that demand is picking up can be spotted in the shipping market. The cost of hiring a tanker on a spot basis East of Suez is at the highest since January. Oystein M Kalleklev, chief executive officer of vessel owner Flex LNG Ltd., expects the LNG market to become “increasingly tight” in the second half of the year, he said Tuesday on an earnings call.

Cargoes for early September delivery to North Asia were bought between high-$3 to low-$4/MMbtu, while October shipments are currently priced around the mid-$4 level, according to traders.

In Europe, where inventories are already above last year’s high point, traders see the gap of as much as $1.50/MMbtu between September and the fourth-quarter contract as an opportunity to sell the fuel later.

One tanker, Marshal Vasilevskiy, which loaded at Rotterdam last weekend, doesn’t appear to have a destination yet and is idling off the port, ship-tracking data on Bloomberg show. Also, at least three BP Plc vessels appear to be idling for longer than usual, according to the data.

S&P Global Platts defines floating storage as any laden trip that takes 1.75 times the standard length of time to reach its destination. The company, which provides commodity price assessments and market analysis, said traders will probably float cargoes for delivery in November and December, boosting prices during autumn in the European market.

“Even if charter rates triple from current levels, marginal LNG spot supply is still profitable selling into November or December,” Platts said in a report. “We expect this dynamic to limit European regasification rates and push LNG storage to its limits in October.”

While an uptick in prices at this time of year is normal, new supply from plants in the U.S. to Australia will likely curb any bigger gains.

A record 35 million tons of LNG capacity will be added globally next year, according to Bernstein. The U.S. alone will add about 17 million tons of capacity between the fourth quarter of this year and the first quarter of 2020, said Leslie Palti-Guzman, president and co-founder of GasVista LLC, an energy consultant in New York. All the new supply, coupled with demand at the mercy of deteriorating U.S.-China trade relations, is sending a bearish signal.

“The market should question the forward winter LNG curve price,” she said.