OPEC, non-OPEC sticking to oil pact but may raise output if needed: Gulf source

DUBAI (Reuters) – Saudi Arabia, other OPEC states and non-OPEC allies aim to stick to a global pact on cutting oil supplies until the end of 2018 but are ready to make gradual adjustments to offset any supply shortage, a Gulf source familiar with Saudi thinking said.

The oil producers participating in the output reduction deal are satisfied with the result of their agreement, which was due to end at the end of 2018, the Gulf source told Reuters.

The deal could be extended to achieve its objectives of keeping a balanced oil market, the source said, adding that, when needed, any rise in output would be “in a gradual and deliberate fashion.”

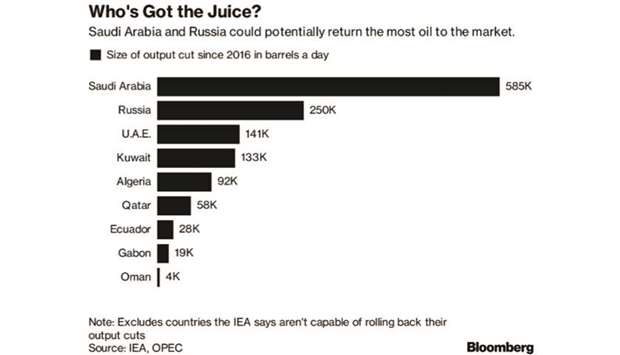

The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries with Russia and several other producers agreed to cut output by about 1.8 million barrels per day (bpd) starting from January 2017. The curbs have driven down inventories and pushed up prices.

The oil market is moving towards balancing and fundamentals are better than last year, “but the group is not ready yet to fully lift controls,” the Gulf source said.

“Saudi Arabia, OPEC and non-OPEC… are continuing their cooperation this year and beyond, it is not something temporary, it is going to be a long-term cooperation for the sake of a stable oil market,” the Gulf source said.

“However, if any shortage takes place, the producers will coordinate closely and promptly take necessary actions. The OPEC and non-OPEC agreement will remain in place. But the level of the cut may be adjusted if a physical shortage arises.”

Raising output would ease about 18 months of strict supply curbs amid concerns that a price rally has gone too far, with oil hitting its highest since late 2014, rising above $80.50 a barrel this month. Prices have since eased.

Sources told Reuters last week that Saudi Arabia and Russia were discussing the possibility of raising output by about 1 million bpd. OPEC meets next on June 22 to decide on policy.

The Gulf source said no decision has been taken about the timing of any increase or the amount, and said Saudi Arabia, OPEC’s biggest producer, favoured “a gradual increase” in output if there was a need.

The source said any decision to increase output in June would coincide with anticipated higher demand in the second half of the year.

“Saudi Arabia favours a gradual approach to increase output to compensate for any unplanned outages. The decision about the timing and amount of oil to raise will be decided when the ministers meet in June,” the Gulf source said.

“The increase in output will be dictated by market conditions and all the numbers circulated about size of the increase or the timing are mere speculation,” the source said, adding that any move would be “a collective action.”

Reporting by Rania El Gamal; Editing by Edmund Blair