Qatar warns war will force Gulf to stop energy exports ‘within days’

Brent crude tops $90 after gas producer says it will take ‘weeks to months’ to restore deliveries

Qatar’s energy minister has warned that war in the Middle East could “bring down the economies of the world”, predicting that all Gulf energy exporters would shut down production within days and drive oil to $150 a barrel. Saad al-Kaabi told the FT that even if the war ended immediately it would take Qatar “weeks to months” to return to a normal cycle of deliveries following an Iranian drone strike at its largest liquefied natural gas plant. Qatar, the world’s second-largest producer of LNG, was forced to declare force majeure this week after the strike at its Ras Laffan plant. While Qatar only exports a small proportion of its gas to Europe, the energy minister said the continent would feel significant pain as Asian buyers outbid Europeans for whatever gas is available on the market, and as other Gulf countries find themselves unable to meet their contractual obligations. “Everybody that has not called for force majeure we expect will do so in the next few days that this continues. All exporters in the Gulf region will have to call force majeure,” Kaabi said. “If they don’t, they are at some point going to pay the liability for that legally, and that’s their choice.” Kaabi’s comments reflect rising concern in the Gulf about the economic repercussions of the US and Israel’s war with Iran, which has wreaked havoc across the oil-rich region. Brent crude rose 5.5 per cent to $90.13 a barrel on Friday following the publication of this article, the highest level since the start of the conflict. European gas prices gained 5 per cent, but were still below this week’s peak. “This will bring down the economies of the world,” Kaabi said. “If this war continues for a few weeks, GDP growth around the world will be impacted. Everybody’s energy price is going to go higher. There will be shortages of some products and there will be a chain reaction of factories that cannot supply.” He said while there had been no damage to Qatar’s offshore operations, the aftermath onshore was still being reviewed. “We don’t yet know the extent of the damage, as it is currently still being assessed. It is not clear yet how long it will take to repair,” he said.

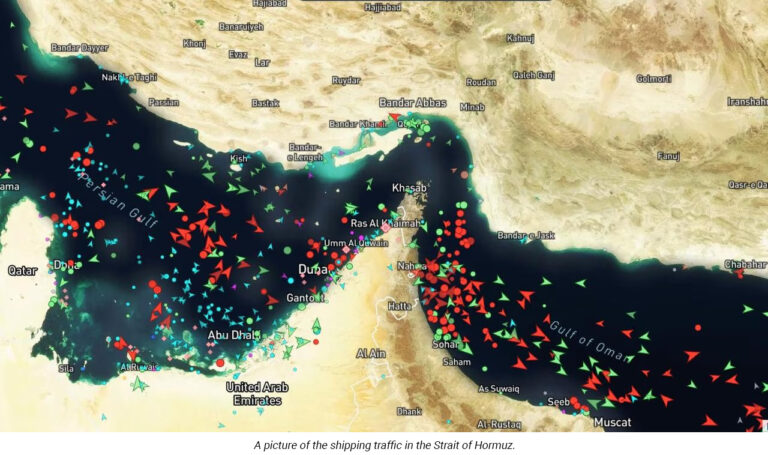

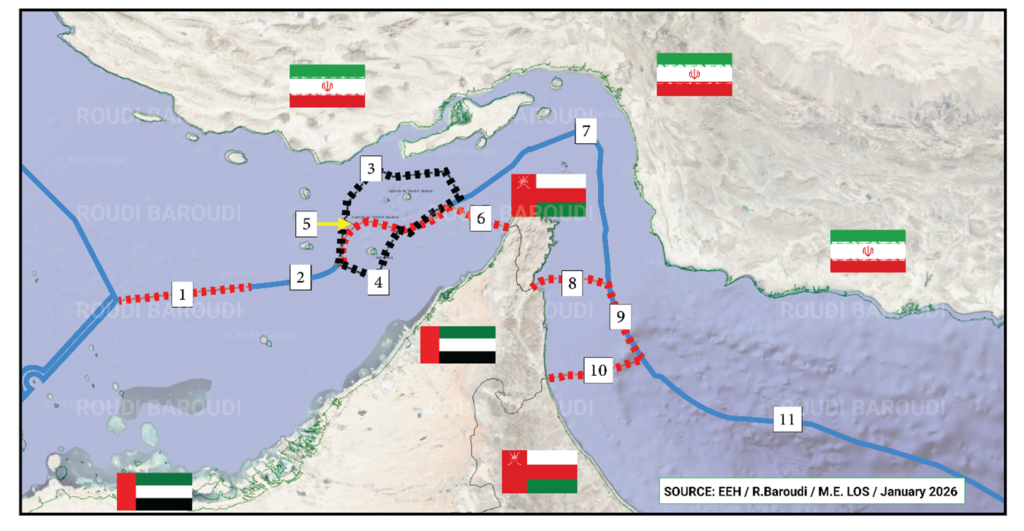

Qatar’s $30bn development to increase production capacity at its vast North Field gasfield from 77mn to 126mn tonnes a year by 2027 would also be delayed, he added. The first production was to begin in the third quarter of this year. “It will delay all our expansion plans for sure,” Kaabi said. “If we come back in a week, perhaps the effect is minimal; if it’s a month or two, it is different.” Saudi Arabia and the UAE both have pipelines that can redirect a portion of their oil exports to be loaded at ports outside the Strait, but significant production volumes remain trapped. He forecast that crude prices could soar to $150 a barrel in two to three weeks if tankers and other merchant vessels were unable to pass through the Strait of Hormuz, a key maritime trade route through which a fifth of the world’s oil and gas passes. He predicted that gas prices would rise to $40 per million British thermal units (€117 per MWh) — almost four times the level they were before the war began. He added that the impact of the disruption of maritime trade through the strait would reverberate far beyond energy markets and hit multiple industries as the region produces much of the world’s petrochemicals and fertiliser feedstocks. Traffic through the waterway has slowed to a halt since the US and Israel launched their attack on Iran on Saturday. At least 10 ships have been hit, insurance premiums have soared and shipping owners have been unwilling to risk their vessels and crews. US President Donald Trump and Israeli officials have warned that the war could last weeks as they seek to destroy the Islamic regime. Trump said this week that the US navy will escort ships through the strait and has offered to provide additional insurance to shipping companies. But Kaabi said it would still be unsafe for vessels to pass through the strait, which is just 24 miles wide at its narrowest point and traces the Iranian coastline, as long as the war was ongoing. “The way that we are seeing the attacks, bringing ships into the strait . . . it’s too dangerous. It’s too close to the shore to bring ships in. It will be difficult to convince ships to go in,” he said. “Most of the ship owners will see that they become a bigger target because they’re [Iran] targeting the military ships.” Kaabi added: “In addition to energy, there will be a halt on all other trade in between the [Gulf] and the world, which will have a significant effect on the economies of the [Gulf] and all the trading partners around the world.” Qatar, which hosts the biggest American military base in the region, has traditionally had good relations with Iran. But the Islamic republic has fired multiple barrages of missiles and drones at it and other Gulf states as Tehran sought to raise the stakes for the US by targeting energy facilities, airports, American bases and embassies.

Kaabi, who is also chief executive of QatarEnergy, said the company had no choice but to declare force majeure after Ras Laffan was hit in an Iranian drone attack on Monday. He cited safety reasons, adding that the company’s offshore facilities were also facing the threat of attack, although they were not damaged. “We were actually informed by our military that there is an imminent threat on the facilities offshore. So we shut down operations safely, as safely as we can, and we mobilised around 9,000 people in 24 hours and brought them back,” he said. “When we have our people in danger and we’re actually being hit in a military zone and we can’t work anymore, and we can’t put our people in harm’s way, we have to declare force majeure.” Production in Qatar will not restart until there is a complete cessation of hostilities, he said. “So the signal is when our military says there is a complete stop of hostilities and we are not being attacked anymore,” Kaabi said. “We are not going to put our people in harm’s way.”

After the restart, he predicted huge logistical issues on top of the restoration of the machinery that cools and compresses gas into liquid that can be shipped. “Our ships are all over the place,” he said, adding that only six or seven out of Qatar’s fleet of 128 tankers were at hand. “Each ship takes a day or two and you can load six or seven at a time,” he added, explaining the length of time it would take to restore normality. He rejected the idea that Qatar’s decision to invoke force majeure and miss shipments would damage the country’s long-cherished reputation as the most reliable supplier of LNG. “We don’t think anybody would dare to come to us and say we are not reliable because you were being bombed and you did not deliver,” he said. Even if it wanted to, Qatar was unable to find gas in the market to make good the lost deliveries to its clients, he said. “Let’s assume you want to buy 77 million and deliver it to customers, there is no 77 million tonnes lying around for you to buy.”

https://www.ft.com/content/be122b17-e667-478d-be19-89d605e978ea