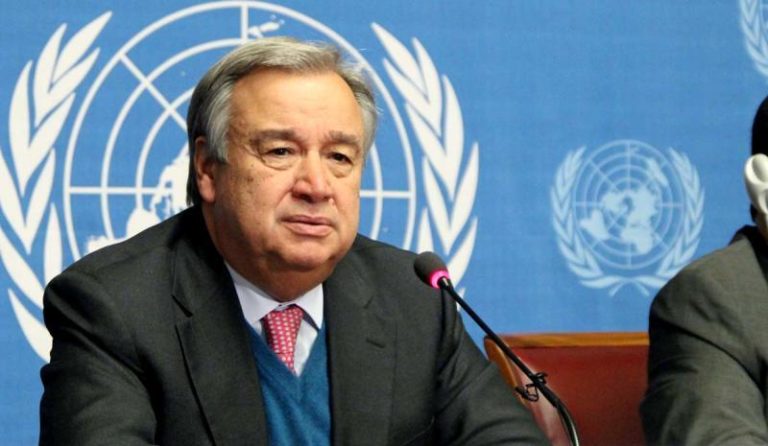

كتاب مفتوح إلى سعادة أمين عامّ الأمم المتّحدة أنتونيو غوتيريس

السيّد أنتونيو غوتيريس

الأمين العامّ

الأمم المتّحدة – الأمانة العامّة

نيويورك، NY10017

الولايات المتّحدة الأميركيّة

المرجع: النّزاعات على الحدود البحريّة في الحوض الشّرقي للمتوسّط: الأزمات والفرص

سعادة الأمين العامّ:

أتوّجه إليكم بكتابي هذا طالباً تدخّلكم الطّارئ في نزع فتيل الأزمة المتراكمة الّتي تؤثّر على المصالح الحيويّة وتطال بشكل مباشر دول ساحل الحوض الشّرقي للبحر الأبيض المتوسّط– وبشكل غير مباشر عشرات الدّول في أوروبا وآسيا وأفريقيا. ان مساعدتكم مطلوبة بشكل خاصّ للمساهمة في حلّ الخلاف حول الحدود البحريّة المتداخلة بين الدّول السّاحليّة تماشياً مع الأصول والإجراءات المنصوص عليها في اتّفاقيّات الأمم المتّحدة والقانون الدّولي.

تدركون ان هذه النّزاعات الحدوديّة الطّويلة الأمد قد تسبّبت بمواجهات عديدة بين الدّول في الماضي، كما أدّى عدد الأزمات الدّوليّة الحادّة الّتي تعصف حالياً بالمنطقة ومحيطها إلى زيادة التوتّرات لتصل إلى مستويات خطيرة. إضافةً إلى ذلك، فقد ساهم الاكتشاف الحديث نسبيّاً لمكامن ورواسب النّفط والغاز الوفيرة في المياه الإقليميّة لعدّة دول في الحوض الشّرقي للمتوسّط في رفع الرّهانات والمخاطر الاقتصاديّة المرتبطة بنزاعات الحدود البحريّة. ونتيجة لذلك، زاد العديد من القوى الكبرى – بما في ذلك الولايات المتحدة وبريطانيا وفرنسا من جهة وروسيا من جهة أخرى – من أنشطتها البحرية وغيرها من الأنشطة العسكرية في المنطقة. وتدركون ان وجود العشرات من السفن والطائرات الحربية في مساحة مغلقة نسبياً يسبّب زيادة الاحتكاكات، وبالتالي يعرّض عمليّة حفظ السلام والأمن في المنطقة للخطر ويعوق التنمية الاقتصادية للدول الساحلية المعنية وشعوبها.

أمرٌ واحد يمكن أن يوفّر فرصة لتحقيق الاستقرار الدائم الغائب عن الحوض الشّرقي للبحر المتوسّط منذ فترة طويلة ألا وهو مقاربة متكاملة متعدّدة الاختصاصات قائمة على استعمال “أفضل قانون” والاستفادة من “أفضل علم” ممّا يؤدي الى ترسيم الحدود البحرية المتنازع عليها بشكل عادل ومنصف. استخدمت الولايات المتحدة مساعيها الحميدة لتعزيز ودعم و/أو العمل كوسيط ودّي بهدف ترسيخ أشكال مختلفة من الحوار بين دول المنطقة. ويبدو أنها أحرزت بعضا من التقدم (خاصةً بين لبنان واسرائيل). صحيح ان هذا الجهد قد ساعد في احتواء التوترات المتصاعدة، ما زال يتعيّن علينا حلّ أيّ من النّزاعات الحدوديّة الرئيسية.

سعادتكم،

أعلم أنني أتحدث نيابةً عن ملايين الأشخاص الذين لم أقابلهم قط عندما أطلب بكل احترام تدخلكم الشخصي في هذه المرحلة الحاسمة والحسّاسة.خصوصا وان أفضل أمل يكمن في تسوية هذه المسائل الشائكة بفعالية بمشاركة أكبر من جانب الأمم المتحدة. وقد تختلف طريقة هذه المشاركة من حالة إلى أخرى وفقاً للظروف. لكن وبشكل عام، فان الأمم المتحدة ومؤسساتها هي من لديها السلطة القانونية والمعنوية لقيادة هذه العمليات إلى نهايات عادلة ونزيهة.

الدّول السّاحليّة السّبعة المعنيّة بموضوع ترسيم الحدود حاليّاً هي قبرص ومصر واليونان واسرائيل ولبنان وسوريا وتركيّا – كلّها دول أعضاء في منظّمة الأمم المتّحدة. (الدّولة الثامنة المعنية بالنّزاع، هي فلسطين، التي تتمتّع بحالة الدّولة المراقبة في الأمم المتّحدة كما تحظى باعتراف أكثر من ثلثي الدّول الأعضاء). في العام 1982 وقع كلّ من قبرص ومصر واليونان ولبنان على اتفاقية الأمم المتحدة لقانون البحار (UNCLOS). أمّا اسرائيل فهي فريق في اتفاقية العام 1958 الخاصة بالبحر الإقليمي والمنطقة المتاخمة، واتفاقية العام 1958 الخاصة بالجرف القاري. كما قامت قبرص بالتوقيع والمصادقة على المعاهدة الأخيرة في حين وقع لكن لم يصادق عليها. فيما سوريا وتركيا ليستا طرفين في أي من معاهدات قانون البحار.

أكّدت محكمة العدل الدّوليّة – وهي الجهاز القضائي الأساسي لمنظّمة الأمم المتّحدة – في حالات عدّة أنّ قواعد ترسيم الحدود البحريّة الّتي تنصّ عليها اتفاقية الأمم المتحدة لقانون البحار (UNCLOS) تعكس القانون الدّولي العرفيّ، وبالتّالي فهي قابلة للتطبيق بشكل عامّ. لقد تطورت مجموعة من الاجتهادات القضائية المتعلقة بترسيم الحدود البحرية من خلال أكثر من عشرين قرارًا اتخذتها المحاكم والهيئات القضائية الدولية وصدرت في خلال نصف القرن الماضي. تقدم هذه الاجتهادات دليلاً مفيداً للغاية للدول الساحلية لمساعدتها في حل نزاعاتها على الحدود البحرية.

بالإضافة إلى ذلك فقد اضحى المشهد العلمي في ايامنا هذه أكثر تحديدًا – وبالتالي أكثر قابلية للتنبؤ به –التكنولوجيّات والتقنيات الحديثة تؤدي الى رسم الخرائط بدّقة متناهية بحيث أنّه يمكن تقدير المتغيرات التّي كانت غير قابلة للتنبؤ بها في الماضي بدقّة مذهلة. ممّا يعني أن أي إجراءات قضائية دولية أو تحكيم أو أي وسيلة أخرى لتسوية النّزاعات المتعلقة بالحدود البحرية لا يكون مرجعها القوانين والقواعد المنشورة فقط، بل أيضًا العلم والتطور التكنولوجي. ونتيجة لذلك، يمكن للحكومات الآن أن تدخل في مثل هذه الإجراءات وهي تعرف تقريبًا ما ستؤول إليه النتائج مع إزالة الكثير من التخمينات التي قد تتسبب في تأجيل الأعمال أو تأخيرها.

بموجب القانون الدولي المعاصر، ولاستعمال القواعد القانونية والعلمية التّي تطبّق على عمليّة ترسيم الحدود البحرية يمكن اعتبار أنّ ما مجموعه 12 حدًا بحريًا يغطي المساحات البحرية للدول السّاحلية السّبع في الحوض الشّرقي للبحر المتوسط. في الوقت الحالي، تمّ توقيع معاهدتين فقط لترسيم الحدود البحرية الثنائية في المنطقة:

1) الاتفاقية بين جمهورية قبرص وجمهورية مصر العربية بشأن تحديد المنطقة الاقتصادية الخالصة تاريخ 17 شباط/فبراير 2003 (دخلت حيز التنفيذ في 7 آذار/مارس 2004)؛

2) الاتفاق بين حكومة الكيان الصهيوني وحكومة جمهورية قبرص بشأن تحديد المنطقة الاقتصادية الخالصة تاريخ 17 كانون الأوّل/ديسمبر 2007 (دخل حيّز التّنفيذ في 25 شباط/فبراير 2011).

ممّا يعني أنّ ما لا يقل عن 10 حدود محتملة وأكثر من ست نقاط تقاطع ثلاثية (أو “نقاط ثلاثية”) – أي أكثر من 83٪ من إجمالي المنطقة البحرية لشرق المتوسط - لا تزال دون حل و/ أو متنازع عليها.

اعتبارًا من شهر نيسان/أبريل 2019، أصبح للدول الساحلية السبع جميعها في الحوض الشّرقي للمتوسّط صناعات هيدروكربونية بحرية نشطة، مع ما يقارب 238,135 كيلومترا مربعا من المياه التي تغطيها حوالي 231 كتلة نفط وغاز متاحة، تمثل أكثر بقليل من 51 ٪ من إجمالي المياه البحرية في المنطقة. ومن ضمن الكتل الحالية المعروضة حاليًا، يمكن تصنيف حوالي 36٪ منها على أنها “مثيرة للجدل القانوني” نظرًا لعدم اليقين فيما يتعلق بالمواقع الدقيقة للحدود البحرية.ونتيجةً لعدم حسم الغالبية العظمى من الحدود البحرية في الحوض الشّرقي للمتوسّط، ستتأثّر التّنمية الاقتصادية المستقبلية الناتجة من اكتشافات الهيدروكربون في قاع البحر واستثماره سلبًا، ممّا يقلل من إجمالي الإيرادات للمنطقة. (ملاحظة: بالنسبة للبحر الأبيض المتوسط ككل يوجد 95 حدًّا بحريًّا ، منها 31 (أو 32٪) تمّ الاتفاق عليها، بينما 64 (أو 68٪) لا تزال دون حل و/أو متنازع عليها).

كما تعلمون جيدًا، وفقًا للمادة 33 من ميثاق الأمم المتحدة ، “على أطراف أي نزاع يحتمل أن يؤدي استمراره إلى تعريض عمليّة حفظ السلام والأمن الدوليين للخطر أن يسعوا أولاً وآخيراً إلى إيجاد حلّ عن طريق التفاوض أو التحقيق أو الوساطة أو التوفيق أو التحكيم أو التّسوية القضائيّة أو اللجوء إلى الوكالات أو التّرتيبات الإقليميّة أو غيرها من الوسائل السلميّة الّتي يختارونها”.

نظرًا للحقوق والواجبات المذكورة بموجب المادة 33 ، وفي أعقاب السابقة الناجحة التي حددها سلفكم في تسهيل اتفاقية العام 2008 بين الغابون وغينيا الاستوائية لإحالة نزاعهما حول الحدود البحرية إلى محكمة العدل الدولية، أطلب منكم وبكلّ تواضع أن تفكروا في تعيين مستشار خاص والتعبير علنًا عن استعدادكم لبدء عملية وساطة للأمم المتحدة تهدف إلى حلّ النزاعات المماثلة في الحوض الشّرقي للبحر المتوسط. تعد مشاركتكم الشخصية و إقراركم ذو أهمية حيوية لمساعدة البلدان المعنيّة على النجاح في حل نزاعاتها الحدودية بشكل سلمي ووفقًا للقانون الدولي.

تجدر الإشارة أيضًا إلى أنّه رغم عدم كفاية الدور النشط للولايات المتحدة لللتوصل إلى حل لجميع النزاعات الحدودية في الحوض الشّرقي للبحر المتوسّط، إلا أن مشاركتها المستمرة ضرورية. خصوصا وأن الوساطة الأمريكية كانت مفيدة بشكل خاصّ في الحدّ من التوتّرات في إحدى أخطر العلاقات في المنطقة – العلاقة بين إسرائيل ولبنان – فإن دعمها لجهود الأمم المتحدة على جبهات أخرى يعتبر شرطاً مسبقاً لنجاح هذه الجهود.

من شأن الخطوات المذكورة أعلاه أن تساعد في غرس زخم جديد في العملية – والثقة بين الأطراف – في فترة حرجة، في وقت تتطلّب فيه الاكتشافات الحديثة لرواسب النفط والغاز في المناطق البحرية المتداخلة بين الدّول اتّخاذ قرارات استثمارية كبيرة من قبل المستثمرين الأجانب وشركات النفط الوطنية في البلدان المعنيّة. أدت الأنشطة الهيدروكربونية في قاع البحر في السنوات الأخيرة إلى سلسلة من الاكتشافات المهمة، من ضمنها اكتشافان هائلان: حقل غاز ليفياثان، اكتشف قبالة ساحل الأراضي الفلسطينيّة المحتلّة في شهر كانون الأوّل/ديسمبر 2010 واحتوائه على 22 تريليون قدم مكعب من احتياطي الغاز؛ وحقل غاز ظهر، اكتشف قبالة مصر في شهر آب/أغسطس 2015 وهو يحتوي على 30 مليون قدم مكعب. يقع كلا الحقلين، اللذين يخضعان لمرحلة التّطوير، على مسافة قريبة جدًّا بشكل عامّ من الحدود التي تحدّدها المعاهدات الثنائية المذكورة أعلاه.

بمجرد تعيينكم لمستشار خاص، سيكون من المفيد أكثر إن تمكنتم من تسهيل عقد اجتماع وزاري متعدد الأطراف حول النزاعات الحدودية في الحوض الشّرقي للبحر المتوسّط في مقر الأمم المتحدة في نيويورك أو في مكتب الأمم المتحدة في جنيف أو في مركز اخر مناسب وملائم. ويمكن تنظيم اجتماعات تحضيرية للفرق الفنية التي تمثل البلدان المعنية قبل هذا الاجتماع الرفيع المستوى ، وهي عملية يمكن بعد ذلك تكرارها على شكل جلسات إضافية في المستقبل.

سعادة الأمين العامّ،

إن قيادتكم النشطة بهدف تأمين حلول مقبولة للاطراف فيما يتعلّق بالنزاعات حول الحدود البحرية في الحوض الشّرقي للمتوسط لن تساعد فقط في تعزيز احترام سيادة القانون الدولي، بل ستساهم أيضًا في تحقيق السلام الدائم وتحسين علاقات الجوار في المنطقة. إضافةً إلى ذلك، فإنّ الحلّ السّلمي لهذه النزاعات سيشكل أيضاً مصدر إلهام للبلدان التي تواجه تحديات مماثلة في جميع أنحاء العالم.

نشكر تفهّمكم سلفاً.

وتفضّلوا بقبول فائق الاحترام،

رودي بارودي

خبير اقتصادي وطاقوي