South Africa’s biggest pot of available cash — 1.91 trillion rand ($128 billion) of civil-servant pensions and unemployment funds managed by the Public Investment Corp. — is emerging as the key to rescuing the debt-stricken national power monopoly.

The money manager has approached its parent agency, the National Treasury, with a proposal to ease the 464 billion-rand load of obligations crushing Eskom Holdings SOC Ltd., signaling officials are gearing up for the complex financial and political operation to convert about 95 billion rand of Eskom debt held by the PIC into equity.

“There’s still a need to undertake a due diligence to confirm the viability of this proposal,” the Treasury said in a Dec. 11 response to questions from Bloomberg, its first statement connecting the PIC to an Eskom bailout. “It is important that the PIC be allowed space to follow its internal governance processes in line with its standard investment evaluation process to mitigate against any possible breach of governance or what could be perceived as political interference.”

While international investors are cheering efforts to contrive a durable fix for Eskom, the idea of tapping the fund is already drawing warnings over the potential fallout. The swap, which could put Eskom into technical default, would pit the government against its own employees, set a precedent that could see other flailing state-owned companies knocking on the PIC’s door and rattle a private sector concerned that its money could be next.

Speculation of a PIC role has intensified in recent weeks since President Cyril Ramaphosa told Bloomberg that “innovative ideas” were being discussed, and Finance Minister Tito Mboweni said the fund was willing to contribute to a solution for Eskom. Labor, business and the government last week agreed to work jointly to reduce the utility’s debt in the so-called Eskom Social Compact.

“The sustainability of Eskom’s debt and the risks it poses to state finances are now arousing political interests who are increasingly interested in grasping a solution,” said Peter Attard Montalto, head of capital markets research at Intellidex. “Eskom’s debt needs to be solved.”

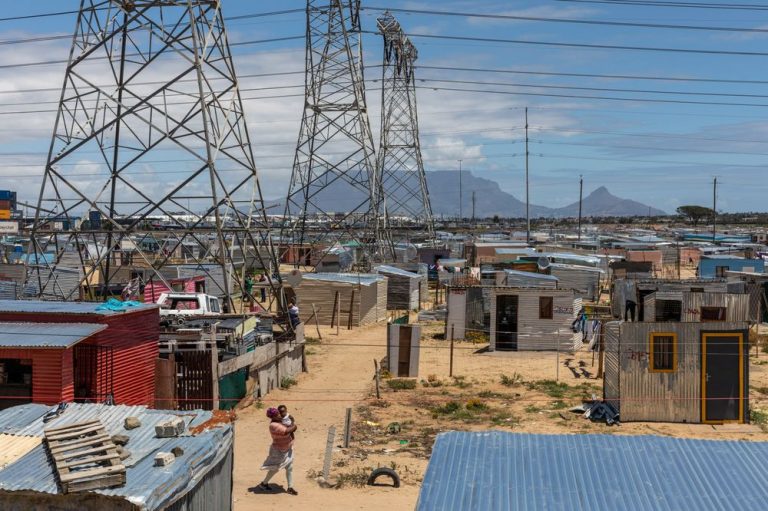

The scope of the task has increased since Goldman Sachs Group Inc. described the utility in 2017 as the biggest threat to South Africa’s economy, which is just exiting its longest recession in 28 years. Eskom’s inability to provide reliable power since 2008, when outages began, has crimped output and disrupted everything from aluminum smelters to household kitchens.

The deterioration was worsened by years of looting under Ramaphosa’s predecessor, Jacob Zuma, leading to the 2019 bailout that totaled 128 billion rand over three years. But that’s merely keeping the wolf from the door and the search for a long-term solution is under way for the too-big-to-fail operation.

‘Materially Cheap’

Plans to rescue Eskom, which has said it can’t afford to service more than 200 billion rand of debt, have also included dipping into the surpluses of state-run unemployment and compensation funds and converting some of its mostly government-guaranteed debt into sovereign bonds.

Credit analysts have been talking up Eskom as a 2021 top pick, citing the government’s efforts, says Lutz Roehmeyer, the chief investment officer at Capitulum Asset Management GmbH in Berlin, who holds Eskom dollar bonds and isn’t adding any more. “Investors are very bullish on the name and expect the sovereign to solve the problem,” he said.

JPMorgan Chase & Co. this week called Eskom bonds “materially cheap” compared with sovereign debt.

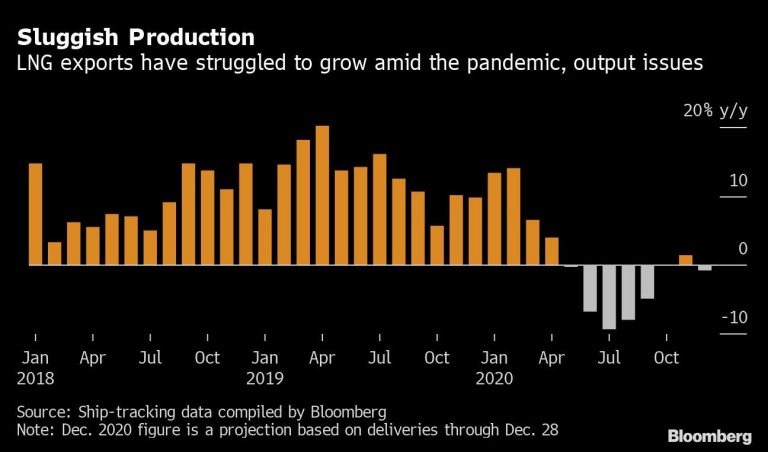

Multiple Bailouts

South Africa’s Eskom is surviving on government support.

“As long as debt declines and becomes more sustainable, that’s really the number one priority,” said Guido Chamorro, co-head of emerging-market hard-currency debt at Pictet Asset Management in London, which manages $10 billion in developing-nation assets, including Eskom 2028 notes. “There are 101 different ways to do it. I mean, the government as the sole shareholder could even assume the debt. Or use its lower funding costs to borrow and then transfer the funds to Eskom.”

The PIC is recovering from a government inquiry last year into how political meddling influenced decision-making. The probe led to the departure of several senior executives following disclosures that included bailing out one of the country’s biggest retailers ahead of a national election against the advice of its investment professionals.

While the Congress of South African Trade Unions, a key ally of the ruling African National Congress, has backed using PIC funds to help Eskom, other labor groups, including the 235,000-member Public Servants Association, and business leaders have opposed it.

Eskom’s own employee pension fund has signaled resistance to the idea. It doesn’t want to change the “risk-return characteristics” of its 2 billion rand investment in the company’s debt or add to the holding, said Chief Investment Officer Ndabezinhle Mkhize.

Pitfalls

All of the options being considered have their pitfalls. A debt-to-equity swap may have to be offered to all creditors and could be classified by ratings firms as a default. Converting Eskom debt into sovereign bonds could flood the market and unnerve holders of South Africa’s 2.62 trillion rand of junk-rated government bonds.

“We could lower the rating by one or more notches if the utility undertakes a debt restructuring, which, in our view, could be tantamount to a default,” Standard & Poors’ said in a Nov. 25 statement.

Eskom CEO Andre de Ruyter has been credited with improving operations since taking over January but has said the debt question is in the hands of the government. He has spoken of using green finance to help reduce coal use and cut its debt. He didn’t give specifics.

Ultimately, unpalatable as it might be, the government may find it just has to meet the utility’s obligations by paying off its debt at it falls due.

“Everybody knows Eskom needs to do something about its debt, no one knows what that looks like,” said Olga Constantatos, head of credit at Futuregrowth Asset Management, which has 194 billion rand under management, including Eskom debt. “It’s in a utility death spiral as well as a debt spiral.”