بارودي: استجرار الكهرباء والغاز من قبرص ينوع مصادر الطاقة ويحميها من أي تداعيات جيوسياسية

تبدو العلاقات اللبنانية القبرصية في حال تطور سريع وقد فتح هذا الباب رئيس الجمهورية العماد جوزاف عون فلاقى استجابة ورغبة عارمة لدى نظيره القبرصي كريستو دوليديس تجاه تطوير العلاقة بين البلدين الجارين وما لفت أن الرئيس القبرصي هو الذي بادر وطرح على الرئيس عون استجرار الكهرباء من قبرص إلى لبنان وقد تلقف رئيس الجمهورية اللبنانية هذه المبادرة وطلب من وزير الطاقة جو صدي متابعة الموضوع.

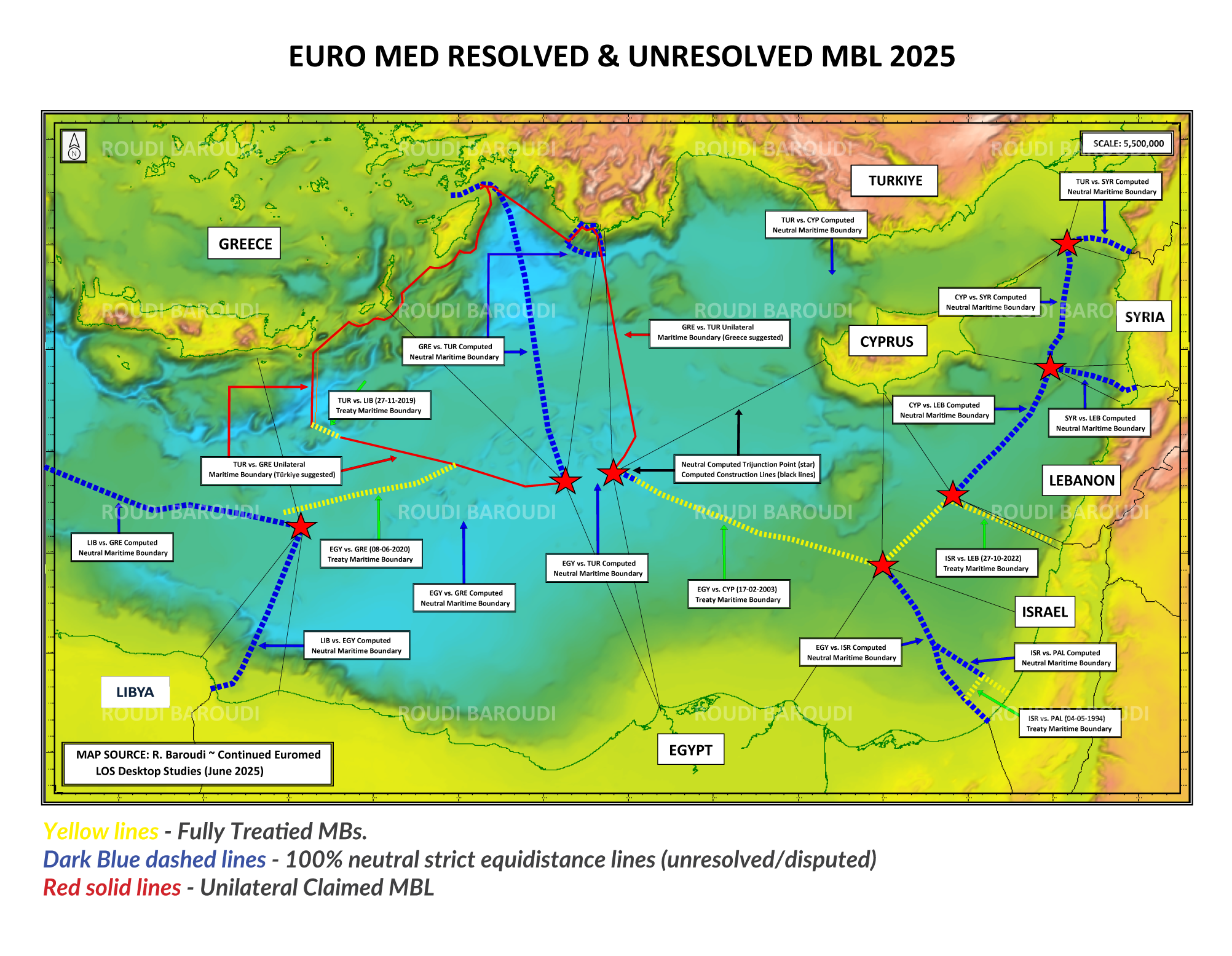

وفي هذا السياق أثنى خبير الطاقة الدولي رودي بارودي على مبادرة الرئيس القبرصي واللبناني، مؤكّدًا وجوب الترحيب بأي خطوة من هذا النوع باعتبارها نقطة انطلاق مهمة لتأمين الكهرباء للبنانيين وحل أزمة القطاع المستفحلة جزئياً منذ عقود وأن هذه الخطوة تأتي بعد الإعلان عن استئناف مفاوضات ترسيم الحدود البحرية بين البلدين.

كما أثنى بارودي على الدور الذي يلعبه الرئيس عون في ملف الطاقة ككل واعتباره أولوية لما فيه من فائدة على الاقتصاد وتعزيز القدرات الاجتماعية للمواطنين اللبنانيين.

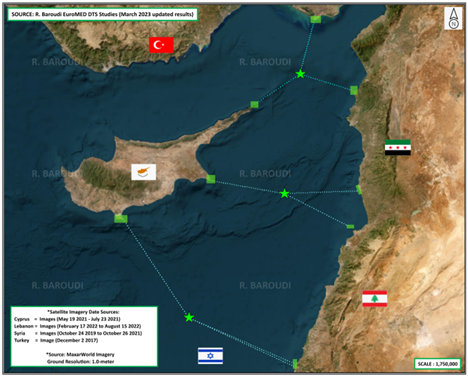

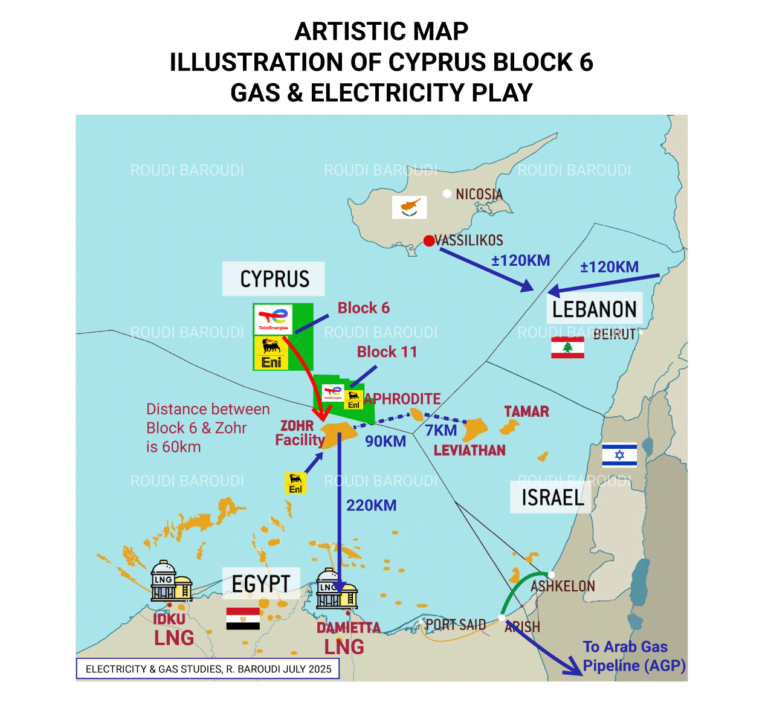

ولفت بارودي إلى أن هذه الخطوة ستتيح تزويد لبنان ما بين 150 و300 ميغاواط وفق مراحل متعددة ولا سيما بعد عام أو عامين على الأكثر عندما تبدأ قبرص بإنتاج الكهرباء من الغاز المستخرج من حقولها البحرية خاصة حقل كرونوس الذي يديره كل من شركتي ENI & TOTAL ENERGIES ما يعزز تنويع مصادر الطاقة وبأسعار مقبولة لا سيما وأن الحقل المعني في قبرص لا يبعد عن حقل زهر المصري سوى ٦٠ كلم ما يعني أن كلفة الإستخراج ستكون مماثلة لتلك المعتمدة في الحقل المصري وهي كلفة رخيصة نوعا ما.

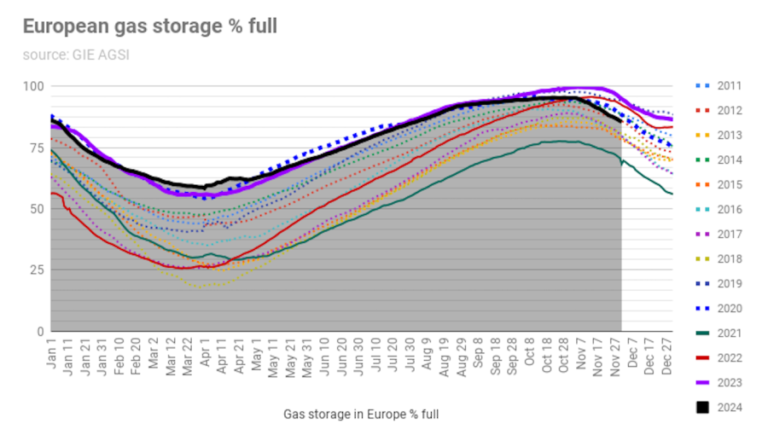

ولفت بارودي إلى وجود محطتين رئيسيتين لإنتاج الكهرباء في قبرص، إحداهما بين لارنكا وليماسول، والأخرى في Vassilikoبين ليماسول وبافوس، بقدرة إجمالية تقار ب 1600 ميغاواط من دون الكهرباء المنتجة من الطاقة الشمسية وبالتالي يمكن للبنان الاستفادة من هذه الطاقة بكلفة يتم التوافق عليها موضحا أن الكلفة ستكون اقل بكثير من كلفة الكهرباء المنتجة في لبنان عندما تبدأ قبرص العام المقبل باستخدام الغاز المستخرج من حقولها البحرية لإنتاج الكهرباء ولاسيما البلوك رقم 6.

بارودي طالب الحكومة اللبنانية بالإسراع بوضع الأطر الإصلاحية والتنظيمية للقطاع بشأن استجرار الكهرباء من قبرص وبإعداد دراسة جدوى اقتصادية تأخذ في الاعتبار كلفة الاستجرار ولفت أن محطة Vassiliko هي المحطة التي تصدر الغاز في 2026، على أن يواصل لبنان مساعيه لربط شبكته بالشبكة السورية للحصول على دعم إضافي كهربائي عن طريق محطة دير نبوح، بما في ذلك محطة الكسارة في منطقة البقاع.