Iran/Etats-Unis: derrière le nucléaire, l’UE voit aussi une guerre du gaz

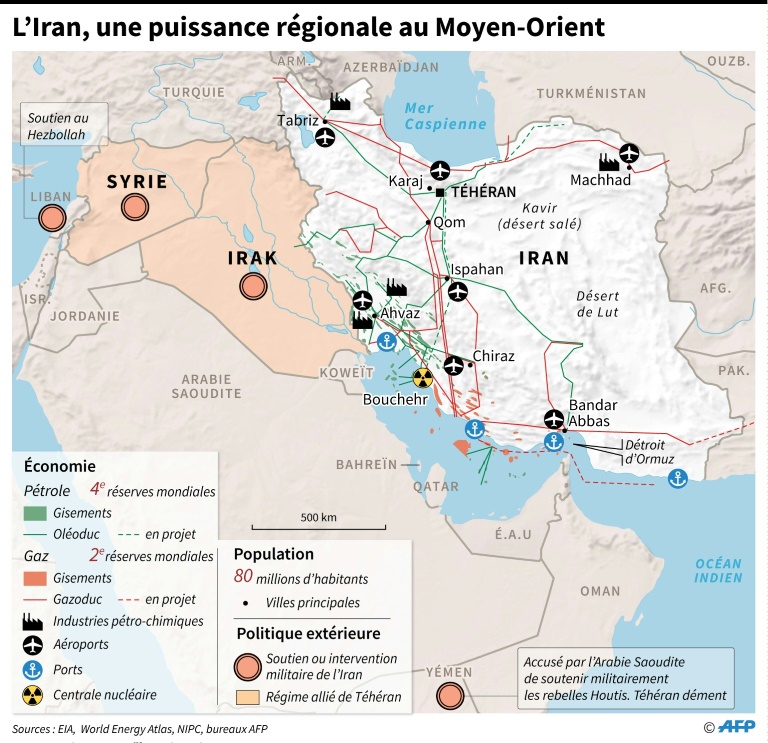

Les Européens soupçonnent les Etats-Unis de chercher à neutraliser l’exploitation des énormes réserves de gaz iraniennes, grâce aux sanctions sur le nucléaire, afin d’ouvrir des débouchés à leur propre production, en plein essor avec le gaz de schiste.

“Les sanctions américaines vont toucher les exportations de pétrole et de gaz iranien vers l’Europe”, relève un responsable européen impliqué dans le dossier.

“Il s’agit clairement d’une nouvelle tentative de limiter une source d’approvisionnement différente afin que le gaz naturel liquéfié (GNL) américain puisse atteindre l’Europe plus facilement, sans concurrents”, explique-t-il à l’AFP sous couvert d’anonymat.

“Je ne crois pas que ce soit le but principal des sanctions contre l’Iran, mais c’est un effet induit”, nuance Marc-Antoine Eyl-Mazzega, directeur du centre Energie de l’Institut français des relations internationales (IFRI).

“Il est clair que les investissements prévus ne vont pas avoir lieu. Je ne connais pas de grande société internationale qui va s’y risquer”, a-t-il pronostiqué dans un entretien téléphonique avec l’AFP.

Au grand dam des Européens, Washington a annoncé réimposer les sanctions levées dans le cadre de l’accord multilatéral conclu en 2015 en échange de l’engagement de Téhéran à geler son programme nucléaire.

Les Etats-Unis menacent Téhéran des sanctions “les plus fortes de l’Histoire” si les Iraniens refusent leurs conditions pour conclure un “nouvel accord” englobant leur programme de missiles balistiques.

Les entreprises européennes qui continueront de faire affaire en Iran dans des secteurs interdits par ces sanctions “seront tenues responsables”, a averti le chef de la diplomatie américaine, Mike Pompeo.

-“Réserves faramineuses”-

L’annonce du possible désengagement d’Iran du géant pétrolier Total et de plusieurs autres entreprises européennes ont été au coeur des récents entretiens à Téhéran du commissaire européen à l’Energie Miguel Arias Canete.

“Les Iraniens doutent de la capacité des Européens à ne pas plier face aux intérêts américains”, a confié à l’AFP M. Canete au terme d’une série de rencontres avec le vice-président iranien Ali Saheli, le chef de la diplomatie Mohammad Javad Zarif et les ministres du Pétrole et de l’Energie.

Les Etats-Unis sont engagés dans une stratégie de conquête de marchés pour leur gaz naturel. Ils ont exporté 17,2 milliards de mètres cubes (m3) en 2017, dont 2,2% par méthaniers vers les terminaux de l’Union européenne. Or “la capacité totale d’importation de gaz naturel de l’Europe va augmenter de 20% d’ici à 2020”, selon le centre d’études IHS Markit.

Chaque année, les pays de l’UE importent deux tiers (66%) de leurs besoins de consommation. En 2017, ceci a représenté 360 milliards de m3 de gaz, dont 55 milliards de m3 de GNL, pour une facture de 75 milliards d’euros, selon les statistiques européennes.

A ce jour, la moitié du gaz acheté est russe, mais les Européens cherchent à briser cette dépendance.

“Les réserves iraniennes sont faramineuses et si l’Iran développe les installations adéquates, elles peuvent permettre à ce pays de devenir un important pourvoyeur (…) pour l’Europe”, plaide M. Canete.

Téhéran possède les plus importantes réserves gazières au monde après la Russie, avec notamment le gisement off-shore de Pars Sud. Elle sont estimées à 191 trillions de m3. Le pays a exporté 10 milliards de m3 en 2017 par gazoduc vers la Turquie et l’Irak. Mais la solution pour l’avenir sera le GNL, transporté par méthaniers, soulignent les responsables européens.

Le ministre du Pétrole, Bijan Namdar Zanganeh, a chiffré les besoins en investissements à quelque 200 milliards de dollars sur cinq ans. Le secteur de l’énergie a fourni 50 milliards de dollars de recettes à l’Etat en 2017, selon les données européennes.

-La Russie ciblée-

L’UE n’est pas la seule dans le collimateur de Washington.

“Un autre concurrent visé est la Russie avec son projet phare Nord Stream 2”, observe le responsable européen.

Nord Stream 2 vise à doubler d’ici fin 2019 les capacités de son grand frère Nord Stream 1, et permettre à davantage de gaz russe d’arriver directement en Allemagne via la mer Baltique, donc sans passer par l’Ukraine.

Le président Donald Trump exige son abandon. Il en a d’ailleurs fait un argument pour exonérer les Européens des taxes sur l’acier et l’aluminium, selon des sources européennes proches du dossier.

La chancelière allemande Angela Merkel défend vivement ce projet de gazoduc stratégique.

“Pour le moment, le GNL américain est plus cher que le gaz russe. Nous avons un libre marché. Le GNL doit être compétitif”, estime-t-on de source gouvernementale allemande.

Mais “Nord Stream 2 n’aide pas à la diversification énergétique cherchée par l’Europe”, reconnaît de son côté le commissaire Canete.

“L’Europe veut développer une stratégie de gaz liquéfié afin d’assurer sa sécurité énergétique, et l’Iran est une source d’approvisionnement importante”, insiste-t-il à l’adresse des Etats-Unis.