Crunch time for the power sector

Many of us take electricity for granted. We flip a switch and expect the light to turn on. But the capacity and resilience of power systems – generation, transmission, and distribution – are not guaranteed, and if these systems fail, it’s lights out for the entire economy.

I recently participated in a meeting of the Power and Energy Society (PES), which operates under the aegis of the Institute of Electric and Electronic Engineers. The mood at the event – attended by more than 13,000 industry professionals from around the world, plus hundreds of companies exhibiting advanced equipment and systems – was upbeat and energetic.

But, despite the prevailing “can-do spirit,” everyone at that meeting knew that the power sector is confronting tremendous challenges, beginning with the growing frequency of extreme weather events. Firms are now working to devise innovative ways to restore power more quickly after outages, and are investing in infrastructure that will increase resilience to shocks. This includes efforts to minimise the risk that the system itself will cause or exacerbate a shock, such as a forest fire.

Compounding the challenge, the power sector must make progress on the green transition. That means reducing its greenhouse-gas emissions, while maintaining a stable power supply for the economy. Since renewables work differently from fossil fuels, this implies a transformation not only of power generation, but also of transmission and distribution, including storage.

Meanwhile, demand for electricity is set to surge, owing to factors like electric-vehicle adoption and the rapid growth of data centres and cloud-computing systems. The power needs of artificial-intelligence systems, in particular, are expected to grow exponentially in the coming years. According to one estimate, the AI sector will be consuming 85-135 terawatt hours per year – about as much as the Netherlands – by 2027.

To meet these challenges, all three components of the power system need to be integrated in so-called smart grids, which are managed by digital systems and, increasingly, AI. But developing smart grids is no small feat. For one thing, they require a host of devices and systems, such as residential smart meters and distributed energy resource management systems (DERMS), which are needed to manage multiple flexible and fluctuating energy sources and integrate them into power networks. And, because they are built on digital foundations, effective cybersecurity systems are essential to support stability and resilience.

None of this will come cheap. The International Energy Agency estimates that, if the world economy is to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, annual investment in smart grids will need to double – from $300bn to $600bn – globally through 2030. This represents a significant share of the estimated $4-6tn that will be needed annually to finance the overall energy transition. But, so far, the required investment has not been forthcoming. Even in advanced economies, the smart-grid funding gap exceeds $100bn.

Meeting all these challenges will require coordinated action across what are often highly complex systems. The US is a case in point. America’s roughly 3,000 electric utilities operate in various combinations of generation, transmission, and distribution, as well as playing a market-making role as intermediaries between generation and distribution. Each US state has its own regulators, and local distribution can be regulated at the municipal level. America’s nuclear infrastructure is managed at the federal level, by the Department of Energy, which also funds research and, under the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act, finances investment in the power sector. And the US Environmental Protection Agency plays a major role in setting the direction and pace of the energy transition.

Other entities oversee the country’s three major grid regions and the interconnections among them. For example, the not-for-profit North American Electric Reliability Corp is responsible for six regional entities that together cover all the interconnected power systems of Canada and the contiguous US, as well as a portion of Mexico.

Achieving the necessary transformation of power systems will require us to figure out how to finance the relevant investments, who will ultimately pay for them, and how a complex, technologically sophisticated, and rapidly evolving smart-grid system can be co-ordinated.

It is difficult to imagine how investment could be mobilized at the scale necessary without the financing power of national governments. This is especially true in the US, where there is no shared carbon price to level the playing field. It is thus good news that, last month, President Joe Biden’s administration announced a range initiatives and investments designed to support and accelerate structural change in the power sector.

As for who should pay, the answer is complicated. In principle, investments that reduce costs or augment service quality and stability should be reflected in tariffs. The problem is that the investments that improve service quality must be spread across multiple entities that own different assets in the grid. Highly decentralised regulatory structures would make coordinating all these tariff changes and transfers unwieldy, at best.

When it comes to investments that advance the green energy transition – including the global public good of emissions reduction – we know who should not pay: local communities. In fact, the implementation of local-level charges to finance such investments is bound to lead to inefficiencies and underinvestment. It would also be unfair: there is no good reason why consumers in areas with problematic legacy systems should pay more. If they are asked to, they are likely to resist.

A better approach would be to use an expanded federal industrial policy not only to help finance and especially to co-ordinate long-term investments in the power sector, but also to guide the development of a complex, interconnected smart-grid system. This system needs a banker and an architect working with firms, regulators, investors, researchers, and industry organisations like the PES to carry out a complex, fair, and efficient structural transformation. National governments need to be involved in filling both roles. – Project Syndicate

- Michael Spence, a Nobel laureate in economics, is Emeritus Professor of Economics and a former dean of the Graduate School of Business at Stanford University and a co-author (with Mohamed A El-Erian, Gordon Brown, and Reid Lidow) of Permacrisis: A Plan to Fix a Fractured World (Simon & Schuster, 2023).

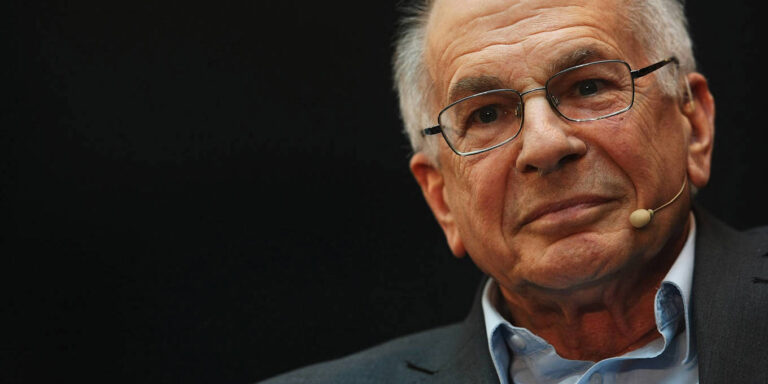

CAMBRIDGE – The recent passing of psychologist and Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman is an apt moment to reflect on his invaluable contribution to the field of behavioral economics. While Alexander Pope’s famous assertion that “to err is human” dates back to 1711, it was the pioneering work of Kahneman and his late co-author and friend Amos Tversky in the 1970s and early 1980s that finally persuaded economists to recognize that people often make mistakes.

When I received a fellowship at Stanford University’s Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences (CASBS) four years ago, it was this fundamental breakthrough that motivated me to choose the office – or “study” (to use CASBS terminology) – that Kahneman occupied during his year at the Center in 1977-78. It seemed like the ideal setting to explore Kahneman’s three major economic contributions, which challenged economic theory’s apocryphal “rational actor” by introducing an element of psychological realism into the discipline.

Kahneman’s first major contribution was his and Tversky’s groundbreaking 1974 study on judgment and uncertainty, which introduced the idea that “biases” and “heuristics,” or rules of thumb, influence our decision-making. Instead of thoroughly analyzing each decision, they found, people tend to rely on mental shortcuts. For example, we may rely on stereotypes (known as the “representativeness heuristic”), be overly influenced by recent experiences (the “availability heuristic”), or use the first piece of information we receive as a reference point (the “anchor effect”).

Second, Kahneman and Tversky’s work on “prospect theory,” which they published in 1979, critiqued expected utility theory as a model of decision-making under risk. Drawing on the “certainty effect,” Kahneman and Tversky argued that humans are psychologically more affected by losses than gains. The perceived loss from misplacing a $20 note, for example, would outweigh the perceived gain from finding a $20 note on the sidewalk, leading to “loss aversion.”

This insight is also at the core of the “framing effect.” The theory, developed while Kahneman was a fellow at CASBS and Tversky was a visiting professor at Stanford, posits that the way information is presented – whether as a loss or a gain – significantly influences the decision-making process, even when what is framed as a loss or gain has the same value.

Lastly, there is Kahneman’s popular masterpiece, the bestselling Thinking, Fast and Slow. Published in 2011 and offering a lifetime’s worth of insights, the book introduced the general public to two stylized modes of human decision-making: the “quick,” instinctive, emotional mode that Kahneman called System 1, and the “slower,” deliberative, or logical mode, which he called System 2. Humans, he showed, are prone to abandoning logic in favor of emotional impulses.

Kahneman received the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2002, despite, as he jokingly remarked, having never taken a single economics course. Nevertheless, his scholarship laid the groundwork for an entirely new field of economic research – and it had all begun in Study 6.

In particular, Kahneman’s work had a profound impact on University of Chicago economist Richard Thaler, who went on to become a Nobel laureate himself. As an assistant professor, Thaler managed to “finagle” a visiting appointment at the National Bureau of Economic Research, whose offices were located down the hill from CASBS, enabling him to connect with Kahneman and Tversky.

In 1998, Thaler co-authored a seminal paper with Cass Sunstein and Christine Jolls, introducing the concept of “bounds” on reason, willpower, and self-interest, and highlighting human limitations that rational-actor models had overlooked. By the time he received the Nobel Prize in 2017, Thaler had systematically documented “anomalies” in human behavior that conventional economics struggled to explain and conducted highly influential research (with Sunstein) on “choice architectures,” popularizing the idea that subtle design changes (“nudges”) can influence human behavior.

But as I gazed at the sweeping views of Palo Alto and the San Francisco Peninsula from the office window at CASBS, the birthplace of behavioral economics, I could not help but wonder whether Kahneman, despite his famously gentle nature, had perhaps been too critical of human decision-making. Are all deviations from “pure” economic logic necessarily “irrational”? Is our inability to align with the idealized model of economic analysis, coupled with our inevitable – albeit predictable – irrationality, really an inherent weakness? And is our tendency to rely on emotions rather than reason a fatal flaw, and if so, could our susceptibility to instinct ultimately lead to our downfall?

I wish I could ask Kahneman these questions. During my time there in 2020-21, Kahneman, affectionately known as “Danny” to all, was not just what CASBS called a “ghost” of the “study” – a former occupant who had been a major influence on my work – but also, happily, a vibrant, living legend who had enthusiastically invited me to discuss these very issues in person. Looking back, I regret my “planning fallacy” in not taking him up on his offer to deepen our conversation sooner – a sentiment shared by both my System 1 and System 2 modes. If “to err is human,” Danny taught me a poignant final lesson in human error.