« LE LIBAN DOIT PROFITER DE LA BAISSE DES PRIX DU BRUT POUR LANCER L’EXPLORATION »

les récentes déconvenues de Chypre – où Total et Eni ont coup sur coup annoncé des résultats de forage négatifs – sont-elles un mauvais signe pour le bassin levantin de la Méditerranée en général, et le Liban en particulier ?

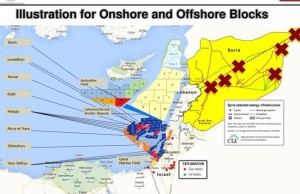

Je ne pense pas que cela remette en cause le potentiel de ce bassin, même si Chypre a peut-être été trop pressé de faire de grandes annonces avant de valider la présence de réserves importantes. Total, qui a des décennies de présence dans la région, reste positionnée sur Chypre, et Eni va continuer ses forages dans les blocs dont elle a obtenu la concession. Pour l’instant, le fait que le bloc 12, attribué à Noble Energy, ne contienne que 4,5 TCF (milliards de pieds cubes) de gaz au lieu des 7 espérés a remis en cause le projet de construction d’une usine de liquéfaction du gaz à Vassilikos. Mais Chypre, et tout le bassin levantin (hors Grèce), peut devenir l’un des principaux fournisseurs en gaz de l’Europe. Il pourrait assurer 20 à 23 % des besoins de ce marché qui cherche à diversifier ses approvisionnements, assurés aujourd’hui à 55 % par la Russie.

Le statu quo continue de prévaloir sur le plan libanais où le processus d’attribution de licences d’exploration est suspendu depuis novembre 2013. La chute des prix du brut ne va-t-elle pas accentuer encore le retard de Beyrouth par rapport à Chypre et Israël en repoussant la date du redémarrage de l’appel d’offres ?

Si l’on réfléchit en termes de production, la baisse des prix internationaux ralentit en effet les activités. C’est la raison pour laquelle Total a estimé qu’il valait mieux ne pas se lancer dans une phase commerciale à Chypre. En revanche, Total sait bien que c’est le moment de poursuivre l’exploration, car les coûts opérationnels et les coûts d’équipements sont au plus bas. C’est le même raisonnement que devrait tenir le Liban. Il doit saisir l’opportunité que représente la chute des cours pour lancer la phase d’exploration en attribuant des licences, sachant que les compagnies auront ensuite trois à cinq ans pour proposer des programmes de production. La priorité doit être de forer. D’abord dans l’idée d’approvisionner le pays pour ses propres besoins énergétiques, et ensuite pour réfléchir à une éventuelle stratégie d’exportation vers l’Europe. N’oublions pas que, juridiquement, ce marché est à 70 kilomètres du Liban. C’est un véritable atout. Il faut cependant au préalable transformer les estimations en matière de réserves en certitudes. Sachant que, tout autour du Liban, il existe des champs gaziers et pétroliers, il n’y a aucune raison de ne pas en trouver ici.

Le niveau des prix du brut devrait-il favoriser le lancement de l’exploration terrestre au Liban ?

Israël vient de lancer la prospection sur le Golan. La Syrie a des réserves prouvées de 2,5 milliards de barils de brut. Le Liban n’a quant à lui toujours pas de loi pour encadrer l’exploration onshore. C’est pourtant le moment de la lancer. La production reste intéressante, même aux niveaux actuels du marché, car les coûts d’exploitation des gisements terrestres sont bien moins chers que ceux des gisements offshores.

(Lire aussi : Le pétrole bon marché, cadeau inespéré pour les consommateurs libanais ?)

Cette capacité de réactivité suppose une vision stratégique et une impulsion politique…

Les deux décrets nécessaires au lancement de l’appel d’offres (sur la délimitation des dix blocs composant la zone économique spéciale et le contrat devant lier l’État aux compagnies) sont prêts et font déjà l’objet d’un accord politique. La loi sur la fiscalité est en cours de finalisation et je ne pense pas qu’elle pose de problèmes majeurs. Ce qui manque, c’est le consensus politique pour redémarrer le processus. Au-delà, le pays doit se doter d’une stratégie nationale en matière énergétique. Et, là encore, le Liban devrait saisir l’opportunité de la baisse des coûts du brut pour réaliser les investissements indispensables en matière d’infrastructures. Je pense en particulier à la nécessité d’alimenter les centrales électriques du pays en gaz. Cela passe par la construction d’un gazoduc le long du littoral dont le coût serait réduit aujourd’hui de 30 à 40 %. Il faudrait aussi louer une centrale flottante de regazéification du gaz naturel liquéfié en attendant de trouver du gaz au large du Liban. Selon mes calculs, l’économie réalisée – coût de location de la barge compris – serait de 600 à 900 millions de dollars par an pour le Trésor, sachant qu’à 90 dollars le baril, les pertes d’Électricité du Liban étaient de deux milliards de dollars par an.