WINNIPEG, Manitoba/NEW YORK, Nov 9 (Reuters) – A U.S. judge in Montana has blocked construction of the Keystone XL pipeline designed to carry heavy crude oil from Canada to the United States, drawing praise on Friday from environmental groups and a rebuke from President Donald Trump.

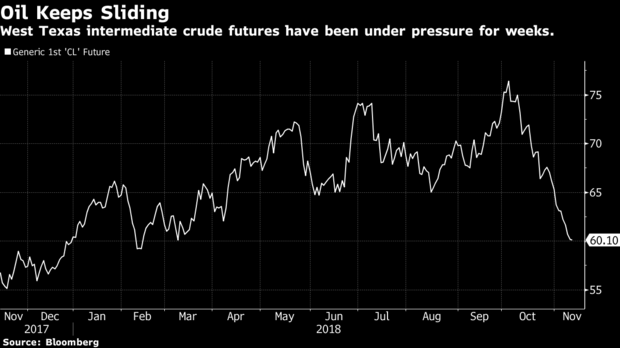

The ruling of a U.S. Court in Montana late on Thursday dealt a setback to TransCanada Corp, whose stock fell 1.7 percent in Toronto. Shares of companies that would ship oil on the pipeline also slid.

TransCanada said in a statement it remains committed to building the $8 billion, 1,180 mile (1,900 km) pipeline, but it has also said it is seeking partners and has not taken a final investment decision.

The ruling drew an angry response from Trump, who approved the pipeline shortly after taking office.

It also piles pressure on Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to assist the country’s ailing oil sector by accelerating crude shipments by rail until pipelines are built. Clogged pipelines have made discounts on Canadian oil even steeper than they were earlier this year when Scotiabank warned that they may cost the country’s economy C$16 billion.

U.S. District Court Judge Brian Morris wrote that a U.S. State Department environmental analysis of Keystone XL “fell short of a ‘hard look’” at the cumulative effects of greenhouse gas emissions and the impact on Native American land resources.

“It was a political decision made by a judge. I think it’s a disgrace,” Trump told reporters at the White House.

The ruling was a win for environmental groups who sued the U.S. government in 2017 after Trump announced a presidential permit for the project. Tribal groups and ranchers also have spent more than a decade fighting the planned pipeline.

“The Trump administration tried to force this dirty pipeline project on the American people, but they can’t ignore the threats it would pose to our clean water, our climate, and our communities,” said the Sierra Club.

The State Department is reviewing the judge’s order and had no comment due to ongoing litigation, a spokesman said.

The pipeline would carry heavy crude from Alberta to Steele City, Nebraska, where it would connect to refineries in the U.S. Midwest and Gulf Coast, as well as Gulf export terminals.

Shares of Canadian oil producers Canadian Natural Resources Ltd and Cenovus Energy lost 2.7 percent and 2.2 percent respectively.

Canada is the primary source of imported U.S. oil, but congested pipelines in Alberta, where tar-like bitumen is extracted, have forced oil shippers to use costlier rail and trucks.

Two pipeline projects have been scrapped due to opposition, and the Trans Mountain line project still faces delays even after the Canadian government purchased it this year to move it forward.

“You have to wonder how long investors will tolerate the delays and whether the Canadian government will intervene again to protect the industry,” said Morningstar analyst Sandy Fielden.

Ensuring at least one pipeline is built is critical to Trudeau’s plans, with a Canadian election expected next autumn.

“I am disappointed in the court’s decision and I will be reaching out to TransCanada later on today to show our support to them and understand what the path forward is for them,” Natural Resources Minister Amarjeet Sohi told reporters in Edmonton, Alberta.

Alberta has felt the financial pressure, and an industry source said the provincial government last month solicited proposals from companies on ways to move crude faster by rail. The source said proposals included ideas such as buying rail cars and investing in loading terminals.

“I’ve never seen (the Alberta government) so active on this front,” said the source, who asked not to be identified because the matter is politically sensitive. “That is a shift.”

Alberta Energy Minister Margaret McCuaig-Boyd said the province has sent a proposal to Ottawa to move crude faster by rail that includes making more tank cars available.

“We’re giving away our resources cheap,” she told reporters. “We need market access.”

Neighboring Saskatchewan stands to lose C$500 million in annual royalties if the discount for Canadian crude remains steep, Saskatchewan Energy Minister Bronwyn Eyre said.

“People have placed quite a lot of hope in that (Keystone) project, so it’s a major setback,” she said in an interview.

Morris, in his ruling, ordered the government to issue a more thorough environmental analysis before the project proceeds. He said the analysis failed to fully review the effects of the current oil price on the pipeline’s viability and did not fully model potential spills and offer mitigation measures.

The ruling likely sets Keystone back by up to one year, said Dan Ripp, president of Bradley Woods Research. (Reporting by Rod Nickel in Winnipeg, David Gaffen in New York and Brendan O’Brien; Additional reporting by Roberta Rampton and Timothy Gardner in Washington, Julie Gordon in Vancouver and David Ljunggren in Ottawa; Editing by Jeffrey Benkoe, David Gregorio and Cynthia Osterman)