Betting against Qatar’s Energy Sector Ignores a lot of history

By Roudi Baroudi

Some of the latest punditry has it that Qatar’s economy is teetering on the brink of disaster because of the COVID-19 crisis, which has been steadily eroding demand for the country’s most important export, natural gas. Obviously the situation is less than ideal, but much of the doom and gloom stems from a failure to appreciate just how well prepared the country is for all manner of obstacles.

Journalists and other observers have watched the market for crude oil collapse to the point where prices for some futures contracts recently went into negative territory – i.e. producers in some parts of North America actually had to pay customers to take oil off their hands. This, in turn, is causing a slew of US and Canadian oil companies, especially smaller ones, to stop extracting crude, and many are going bankrupt. Similar pressures will arise for gas producers, these folks argue, and since Qatar is the world’s leading producer and exporter of liquefied natural gas (LNG), it will face the biggest problems.

To be sure, the global crisis caused by COVID-19 has subjected the entire world to some freakish pressures, including unprecedented drop-offs in demand for certain goods and services, among them several energy products previously soaked up by (now idled) planes, trains, and automobiles (not to mention cruise ships, factories, hotels, etc.). Thus far the consequences for LNG have been less dramatic than those for crude oil, but nor can they be ignored, especially for developing countries whose economies and financial stability are heavily dependent on constant flows of gas revenues from exports.

For multiple reasons, however, Qatar has to be considered far more resilient than other major LNG producers. For one thing, it has much deeper pockets that give it considerable wherewithal to withstand even a prolonged period of lower gas revenues. For another, Qatar’s energy interests go far beyond the extraction of its gas resources for export. It is now fully engaged at several points along the hydrocarbon value chain, and this in multiple countries, all of which provide diversification of revenues and therefore dilution of negative impacts. Perhaps most importantly, for almost three years now, the country has been fortifying itself against the effects of an illegal economic and transport blockade led by Saudi Arabia and followed by several other Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) member states, plus Egypt and others. To say the least, Qatar has proved a tough nut to crack: in fact, the experience has made the whole country much more efficient, far more self-sufficient, and even more self-confident than ever before.

One of the drivers of this success has been government-owned Qatar Petroleum (QP), one of the strongest and most influential companies on the planet, and it has not got to this position by simply opening a spigot in the sand and then spending the proceeds. Instead, QP reached its current lofty status by, first, making its bet on LNG at precisely the right time in history, just as the environmental concerns associated with oil made natural gas a more palatable choice and the world’s energy mix started transitioning to a higher proportion of renewables and other alternative technologies. Second, Qatar then used its role as the world’s most important LNG exporter to become a force for stability in a burgeoning global gas market, maintaining safe and reliable supplies that have allowed customers around the world to grow their economies.

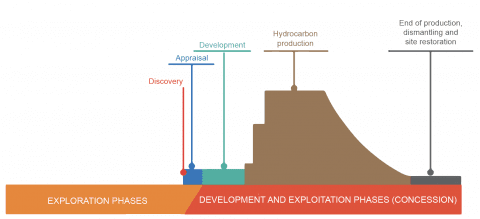

Second, QP has not remained a one-trick pony. Instead, it and its subsidiaries have diversified with gusto – and not just in the usual sense of producing petrochemicals, aluminum, and fertilizers on their home turf. Rather, the company has reached far beyond Qatar, the GCC countries, and even the broader Middle East and North Africa region to make acquisitions around the globe. Acting alone or in concert with major partners like Britain’s Shell, France’s Total, Italy’s ENI, and the USA’s Chevron and ExxonMobil, the past couple of years have seen QP take up or renew stakes in exploration, production, and/or processing assets in at least a dozen countries, including Argentina, Brazil, Cyprus, Congo Brazzaville, Guyana, Ivory Coast. Kenya, Mexico, Morocco, Mozambique, Namibia, Oman, South Africa, and even the United Arab Emirates.

Perhaps the biggest play of the past few years has been in the United States, where QP’s activities have included partnering with ExxonMobil (Qatar’s single largest foreign investor) for a $10 billion project to build a two-train LNG export facility adjacent to the existing Golden Pass import terminal in Texas. QP also added to its footprint in the USA by teaming with Chevron Phillips Chemical, a joint venture between Chevron and Phillips 66, to develop what could be the world’s largest ethane cracker and derivatives units somewhere on the US Gulf Coast. QP will have a 49% stake in the $8 billion complex, and Chevron Phillips Chemical has agreed to build virtual twin of it at Ras Laffan – hub of Qatar’s gas industry.

Alongside its solid American investments, the company also continues to consolidate its access to existing markets in Europe and Asia, and to increase its capacity to supply those markets. It has recently signed long-term processing and/or storage contracts at terminal facilities serving key LNG markets, including Montoir-de-Bretagne, France (3 million tons per annum [MTA] until 2035), and Zeebrugge, Belgium (100% of regasification capacity until 2044). In addition, QP subsidiaries hold stakes in major terminals like the United Kingdom’s South Hook (67.5%) and Italy’s offshore Adriatic facility (23%). In April, it signed a $3 billion contract to book a Chinese shipbuilder for the construction of new LNG carriers, some 100 of which it expects to need in the coming few years.

All the while, QP has continued to rack up agreements with both new and existing customers, including LNG sales to Kuwait and Vietnam; naphta deals with Japan’s Marubeni Corporation, Shell, Thailand Chemicals, and Vietnam; condensate feedstock sales to ExxonMobil in Singapore; and liquefied petroleum gas contracts with China’s Oriental Energy and Wanhua Chemicals.

And all this is not to mention QP’s massive undertaking to expand LNG output from 77 MTA to more than 110 MTA. When the COVID crisis hit, far from fretting the short- and medium-term obstacles, the company’s response was to double down and take advantage of lower prices for construction materials by increasing capacity to a whopping 126 MTA by 2027.

It should be recalled, too, that QP has managed all of these feats while its home country has been fending off the aforementioned Saudi-led siege. Qatar’s public and private sectors alike have demonstrated world-class resilience since the blockade was imposed in 2017, so there is no reason to believe they will shrink before this new challenge. On the contrary, Qatar is – and will remain – a trusted source of stabilization in global markets.

Whatever the temporary inconveniences caused by the pandemic, both Qatar and QP remain bullish on the future – and with good reason. They did not get to where they are by accident, rather by well-timed investments and a commitment to ensuring stable markets for their customers. In fact, it could be fairly stated that Qatar and its flagship gas company created the modern global gas market, and they did so in such a way as to deliberately avoid much of the volatility associated with crude oil – for instance by eschewing the establishment of a cartel like OPEC. The current crisis could well require Qatar to make uncomfortable decisions, but its long-term trajectory – to keep expanding its role as a force for good in energy circles by providing win-win scenarios – is unlikely to be affected.

Roudi Baroudi is a four-decade veteran of the energy industry who currently serves as CEO of Energy and Environment Holding, an independent consultancy based in Doha.