Asian markets, military allies and a crucial pipeline all offer Doha leverage against its adversaries amid the current crisis

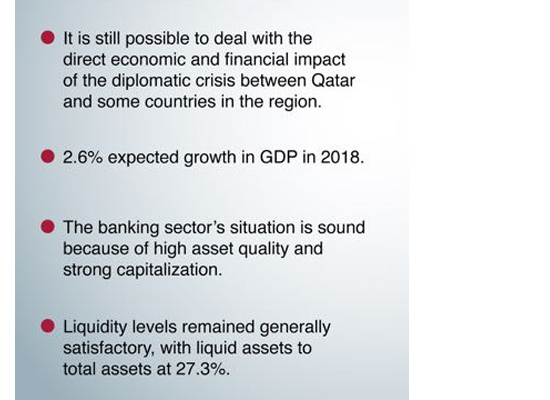

The blockade of Qatar, led by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, has already had an economic impact.

Qatar, the world’s second largest producer of helium, has stopped production at its two plants as it cannot export gas by land. Qatar Airways can no longer fly to 18 destinations. Qatari banks are feeling the pinch, particularly the Qatar National Bank (QNB), the region’s largest by assets, and Doha Bank: both have extensive networks across countries which are members of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC).

Ratings agency Standard & Poor’s (S&P) downgraded Qatar’s credit rating from AA to A- on 8 June. It could put it on credit watch negative, a sign that the crisis could impact investment and economic growth. Moody’s followed suit, placing Qatar’s AA long-term foreign and local currency Issuer Default Ratings (IDRs) on rating watch negative.

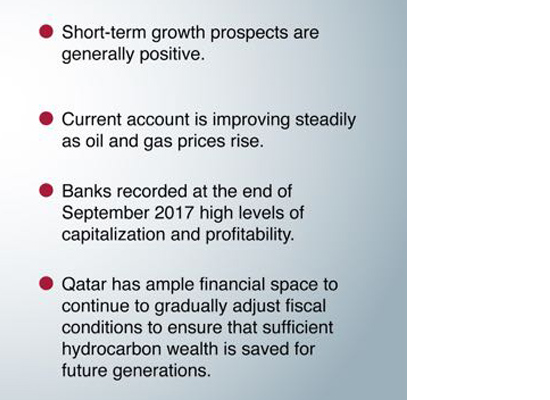

Doha is unlikely to buckle soon. It has plenty of financial muscle, not least in its sovereign wealth fund, the Qatar Investment Authority (QIA), which holds an estimated $213.7 billion, according to the Institute of International Finance. The seed capital for that fund comes from Qatar’s oil and gas exports.

Energy receipts account for half of Qatar’s GDP, 85 percent of its export earnings and 70 percent of its government revenue. The crisis may affect the emirate’s medium- to long-term energy contracts, as buyers diversify their imports to be less reliant on Qatari gas.

Roudi Baroudi is CEO of Energy & Environment Holding (EEH), an independent consultancy (the principal holder in EEH is Sheikh Jabor bin Yusef bin Jassim al-Thani, director general of the General Secretariat for Development Planning). He says that when it comes to oil, the advantage is with the Riyadh-led group: Saudi Arabia recently overtook Russia as the world’s biggest producer; the UAE is also in the top 10.

“When it comes to gas, however, Qatar holds more and better cards,” Baroudi adds.

Doha can use energy as a diplomatic tool to its advantage: how it does this will be crucial as to its attempts to ride out the current storm.

How will Qatar ship its exports?

Qatar is the world’s largest liquefied natural gas (LNG) exporter, accounting for nearly one-third of global trade, at 77.8 million tonnes (MT) in 2016, according to the International Gas Union. So far there have been no interruptions to Qatari extraction or exports via the 60-plus LNG carriers that belong to the Qatar Gas Transport Company (Nakilat in Arabic).

But as a result of the crisis, state-owned firms Nakilat, Qatar Petroleum and Industries Qatar have all been downgraded.

Much of Qatar’s liquefied natural gas is shipped by tanker. While there have been no reports of oil shipments being interrupted, there is concern about Qatari routes to Asia, the key buyer for the bulk of its oil as well as much of the Gulf’s exports.

Historically, Asian buyers demand a mixture of crude oil from the Gulf: usually the taker would depart the emirate with Qatari oil, then stop to refuel and add Saudi, Emirati and Omani grade crude, usually at UAE ports.

Karim Nassif, associate director at Standard & Poor’s in Dubai, says: “If they are not allowed to stop and refuel as some reports suggest, then this could affect the buyers who may be anticipating a variety of crude grades.”

The Daily Telegraph reported that two LNG ships bound for the UK were re-routed due to the crisis, but Baroudi says this is not an issue. “If the reports are true, it’s just a by-product of how international companies are coping with the Saudi-led embargo by playing it safe.

“Say Company A was planning to deliver LNG from Qatar to the UAE, but the latter now bans Qatari ships from docking and unloading. Company A’s response may well be to send an LNG carrier based in a third country to make the delivery instead, then reroute one or more others to make sure all customers are supplied.”

Naser Tamimi, an independent Qatari energy expert, says that the same scenario applies to the possibility of Egypt stopping Qatari tankers using the Suez Canal; or raising fees for Qatari vessels. “The Qataris could get around it through tankers registered elsewhere, like the Marshall Islands,” says Baroudi, “or divert some of their cargo going to Europe via South Africa.”

He says that such moves could add about half a dollar to the cost of each British Thermal Unit (BTU) – but that the Qataris could cope with that, even if they had to absorb the cost instead of the consumer.

Around 70 percent of Qatar’s LNG exports are under long-term contracts – typically of around 15 years – so production and payments are secure. The remaining exports are on short-term or spot prices that are dictated by the international markets.

Sources within the shipping industry speculate that some deals may have been called off or delayed: there have been reports from insurance and petrochemical companies that 17 LNG vessels are now moored off Qatar’s Ras Laffan LNG port – a much higher number than the usual six or seven vessels.

Will Asian markets look elsewhere?

The bulk of Qatar’s LNG is destined for east Asia – and analysts say that that is unlikely to end soon.

Theodore Karasik, senior adviser at Washington-based consultancy Gulf State Analytics, says: “Qatari LNG is not affected by the sanctions and blockades, simply because GCC states require good relations with east Asian partners.”

He said that if Saudi Arabia and UAE were to interrupt LNG exports to Asia, then those customers may not want to invest in the programmes intended to transform the economies of the UAE or Saudi Arabia, such as the 2030 Visions strategies.

His opinion is echoed by Baroudi. “The Asian markets aren’t going anywhere. Asian countries need – and know they need – long-term relations with stable producers, and by this measure Qatar is in a class by itself. The same applies for consumer nations elsewhere, so even if the crisis were to escalate, and right now it appears to be settling down, then any interruption would be a short-term phenomenon.

“Qatari LNG simply cannot be replaced. Australia [LNG] will begin to have an impact on international markets by the end of the decade, but that just means an added degree of market competition, not replacement.”

But Tamimi thinks the crisis could prompt Asian buyers to diversify their energy portfolios and lessen their dependency on Qatari gas. “They are under pressure now, and in a global context with an LNG glut,” he says.

“All Qatar customers are asking for better deals, and Qatar’s market share is decreasing compared to 2013 because of competition from Australia, Indonesia and also Malaysia. The crisis is a reminder to everyone in Asia that the Middle East is not stable, that everything could change within days.”

Will Qatar shut down a key pipeline?

One scenario that would deepen the crisis still further is a lockdown of the Dolphin gas pipeline, which runs between Qatar and some of its fiercest critics.

While two-thirds of Qatari LNG is bound for Asia and Europe, around 10 percent is destined for the Middle East. Two export markets, Kuwait and Turkey, are secure due to better political relations.

But the other two – Egypt and the UAE – are among those nations currently blockading Qatar. If Riyadh and the UAE raise the ante, then it might raise questions about the pipeline’s future.

Egypt gets two-thirds of its gas needs, some 4.4 MT in 2016, from Qatar on short-term and spot prices. Cairo is firmly in the Saudi camp – but has not halted gas shipments.

Baroudi says: “Since the crisis erupted, Egypt has continued to accept shipments of Qatari gas on vessels flying other flags. The 300,000 Egyptians who live and work in Qatar have carried on as before.

“Neither country wants to burns its bridges for no good reason,” he says, “especially Egypt, which only recently staved off bankruptcy because of Qatari financial largesse,” a reference to the $6 billion Qatar provided in the wake of the 2011 Egyptian uprising.

But it is the Dolphin pipeline, which carries Qatari gas to the UAE and Oman, that is the most contentious issue. The UAE imports 17.7 billion cubic metres (BCM) of natural gas from Qatar, according to the BP Statistical Review 2016, equivalent to more than a quarter of the UAE’s gas supply.

Nassif says: “The Qataris have indicated that the supply of gas through Dolphin to the UAE and Oman will continue. We have no concerns at present of any armageddon scenario of Qatar changing its stance on this.”

Either side would lose significantly if the gas was stopped, especially during the summer when power generation is at its peak to keep the air conditioning on. Halting supply would be the Gulf equivalent of Russia turning off the gas to Ukraine in January 2009.

“The UAE would immediately face extensive blackouts without it,” says Baroudi. “They would be shooting themselves in the foot if they were to interfere with gas shipments, and Qatar views the pipeline as a permanent fixture, not something to be manipulated for the sake of short-term political gain.

“As a result, neither side has any interest in changing the status quo – and neither has communicated any consideration of such a step.”

Analysts say that both sides have contingency plans should the Dolphin pipeline shut down – but, says Tamimi, the UAE will find it hard to compensate for the loss of Qatari gas.

“They’ll have to import LNG as no one can send it by pipeline. That will cost three times the price they’re getting from the Qataris. There is no official price but it is estimated at $1.6 to $1.7 per BTU, so around $1.1 billion [in total].

“If the UAE wants to stop the Qatari imports, they’d have to pay three times that amount at the current price as LNG is linked to the price of oil.”

A stoppage on either side would also violate bilateral agreements. “If the UAE violates it, the Qataris can sue them and vice versa. If the Qataris do it, it would also send a bad message to their customers, to use gas for political reasons.”

Such a move by Qatar would also undermine its strategy of saying it has been unfairly treated by the GCC and is abiding commercial contracts – unlike the UAE and Saudi Arabia, as Qatar Airways CEO Akbar Al-Baker told the press.

Will there be a land grab by Saudi?

Analysts have not ruled out further sanctions by the UAE and Saudi amid the current crisis. Any move on blocking energy exports, including the Dolphin pipeline, would be viewed as a serious escalation by Doha as it would cripple its economy.

One hypothetical scenario being actively debated at a political level, according to analysts, is an all-encompassing blockade of Qatar as part of Riyadh’s and the UAE’s plans to re-organise the Gulf Cooperation Council – and, unless there is a change of regime in Doha, kick out Qatar (let’s call it a “Qatexit”).

An extension of this scenario is an outright land grab by Saudi Arabia of Qatar’s energy assets. These would then fund Deputy Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s Vision 2030 strategy to diversify the kingdom’s economy.

Karasik says: “Arguably the national transformation plan and Vision 2030 may not be going so well. In addition the ($2 trillion) Saudi Aramco IPO may not achieve its fully stated value. If this is the case, then Saudi is going to need an injection of wealth and will have to do it fast.

“In other words, Riyadh may look for a piggy bank to rob.”

Such a move by Riyadh would be armageddon for the Qatari royal family. The emir of Qatar would be forced to stand down – as Emirati real estate mogul and media pundit Khalaf al-Habtoor has suggested – or Riyadh could take control of the kingdom.

Baroudi believes that the crisis is settling down and will soon be resolved. Other analysts have pointed to the recent $12 billion US fighter jet deal with Qatar, indicating that Riyadh and the UAE will not get their way. The Al-Udeid US air base, which is the headquarters of Central Command, covers 20 countries in the region.

Turkish troops, who arrived in Qatar for training exercises this week, could also help turn the heat down, now that the two countries have signed a defence pact. Ankara has the region’s largest standing army, with its presence near the Saudi border (Qatar’s only land border) considered a deterrent.

But other analysts see no sign of tension ebbing soon. They flag how the descendants of Ibn Abd al-Wahhab – the founding father of Wahhabism, both Saudi and Qatar’s dominant theology – have distanced themselves from the emirate’s ruling family, undermining its legitimacy. The rhetoric against Qatar from Riyadh and the UAE continues unabated. Last week, the UAE called on the US to move the Al Udeid air base out of Qatar.

“There are no more black swans in our world,” says Karasik. “This idea [of a land grab] is something people are starting to talk about.”

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.