Russia’s proposed TurkStream 2 pipeline sparks Bulgaria, EU energy worries

Russia is pushing for a new gas pipeline running through Bulgaria that could supply Western Europe with energy.

But does the TurkStream 2 proposal threaten to strengthen the Kremlin’s influence over the European Union?

Bulgaria is considering joining Russia’s TurkStream 2 pipeline proposal and, according to the country’s Ministry of Energy, is ready to invest €1.4 billion ($1.6 billion) in the project.

Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev is set to travel to the country next week, where he is expected to discuss the pipeline. However, its completion is dependent on approval from the necessary authorities, including the European Commission. Experts have already expressed doubts over whether the pipeline will be profitable (in fact, only the third market test was successful), implying that the government in Sofia is working to further Russian interests.

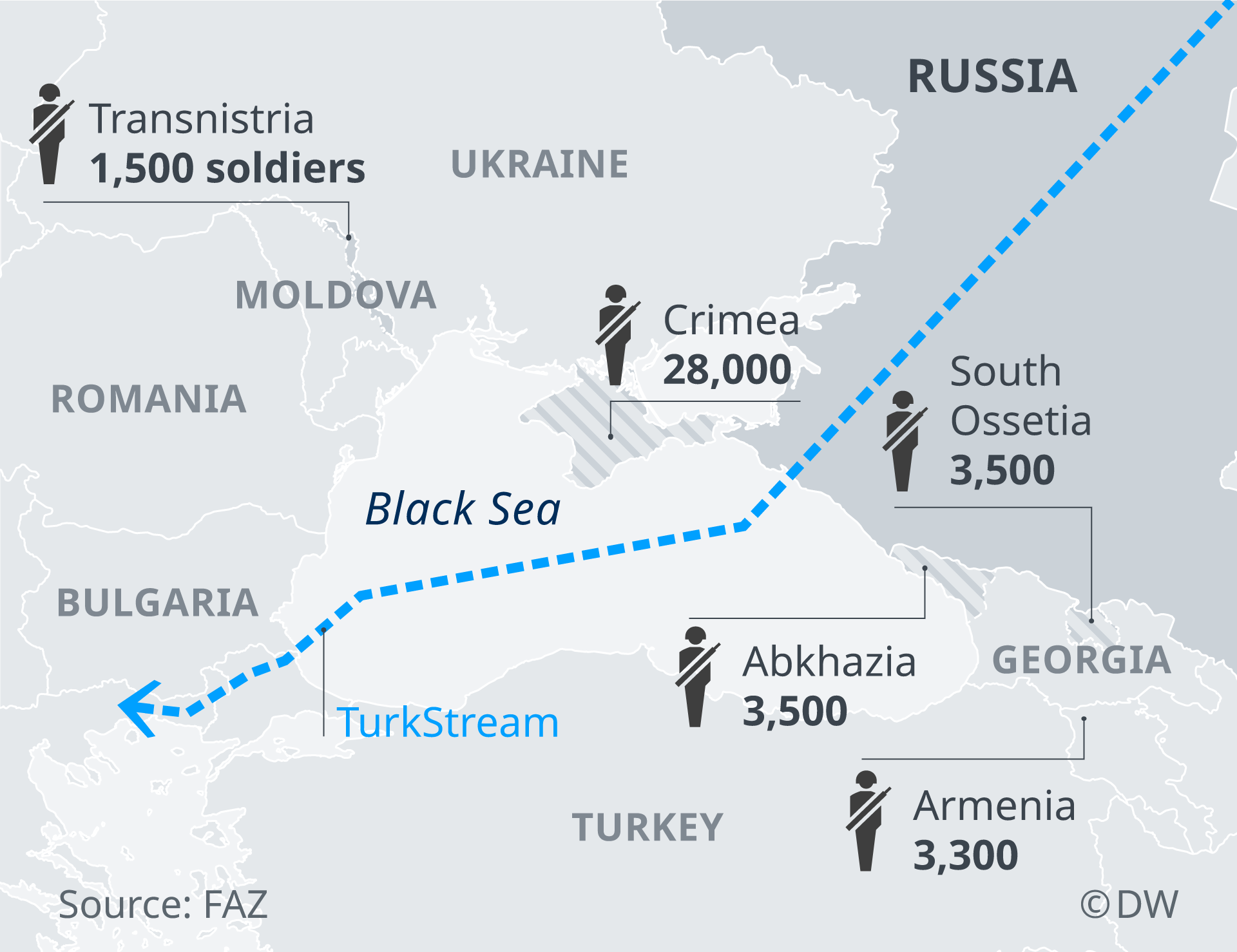

The original 910 kilometer-long (565 mile) TurkStream gas pipeline runs under the Black Sea, linking Russia and Turkey. This project is due to be completed by the end of this year, along with the Power of Siberia pipeline, which links Russia to China, and the Nord Stream 2 pipeline from Russia to Germany. Turkey is Russian energy giant Gazprom’s second biggest client after Germany.

arket. Gazprom has two options for reaching Western Europe: either through Greece and Italy or through Bulgaria, Serbia, Hungary and the Baumgarten hub in Austria. Earlier in February, Gazprom CEO Alexei Miller met Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic to discuss the pipeline project. However, the chairman of Greece’s main opposition party, New Democracy, said on Thursday ahead of a two-day visit to Moscow that his country was considering whether to allow the new pipeline through Greek territory.

Russian gas an EU dependence

The European Union currently imports most of the natural gas it uses. According to Eurostat data, for the first semester of 2018, 40.6 percent of this imported gas came from Russia, followed by Norway and Algeria. Until recently, most of the Russian gas supplied to the EU ran through pipelines crossing Ukraine. After the revolution that forced pro-Russian President Viktor Yanukovych from office, and the subsequent annexation of Crimea by Russia in 2014, relations between Moscow and Kyiv deteriorated. The Nord Stream and TurkStream pipelines allow Russia to supply natural gas to Western Europe without running through Ukrainian territory, thus denying Kyiv transit fees and billions of euros in profit.

Sixty-seven percent of Russia’s tax revenues come from energy exports, particularly gas, which is a powerful political instrument for the Kremlin. Companies such as Gazprom, as well as virtually all Russian resource oligarchs, operate under the Kremlin’s benevolent eye. And, in numerous cases, the elites in countries such as Bulgaria, Serbia and Turkey are tempted by Russian overtures. Furthermore, the supporters of the Nord Stream pipeline in Germany and within the Hungarian government, including Prime Minister Viktor Orban, have been accused of enabling Russia’s geopolitical power games.

Bulgaria is highly dependent on the import of Russian energy: more than two-thirds of the gas it consumes domestically comes from Russia. On the eve of Bulgaria’s accession to the EU in 2007, Vladimir Chizhov, Russia’s ambassador in Brussels, playfully called the country “our Trojan horse in the EU, in the good sense.”

In 2014, the Bulgarian government abandoned TurkStream’s predecessor, the South Stream gas pipeline, due to pressure from Brussels, which said the project wasn’t compliant with EU legislation. In an effort to avoid potential sanctions, Gazprom has now chosen a Russian company — oil and gas pipe maker TMK, which arguably has “no connections” to Gazprom — to construct the pipeline, according to the Russian news outlet RBC.ru.

The Russian lobby in Bulgaria

The pro-Russia lobby is a powerful force within Bulgarian politics. Volen Siderov, the leader of the populist right-wing party Ataka, is a great admirer of Russian President Vladimir Putin, for instance. What’s more, Valentin Zlatev, a key figure in the energy sector and the CEO of Lukoil Bulgaria, which belongs to Russian multinational corporation Lukoil, has been described as the kingmaker of Bulgarian politics.

According to Transparency International, Bulgaria continues to have the highest level of corruption within the public sector among EU member states. While relations between power brokers in Sofia and Moscow are often based on pragmatism, the majority of the country’s population still harbors a special sympathy for Russia.

However, two particularly thorny issues between Bulgaria and Russia threaten to complicate progress on the TurkStream 2 project. The deputy chair of Bulgaria’s ruling party, GERB, has warned that the upcoming European Parliament elections could be vulnerable to Russian interference. Furthermore, the poisoning of the Bulgarian arms dealer Emilian Gebrev in 2015 has been linked to the case of Sergei Skripal and his daughter in the United Kingdom last year. There are allegations that both Skripal and Gebrev were targets of Russian intelligence operatives.