Lebanese – Syrian Maritime Boundaries: Solutions Are Ready

By Roudi Baroudi

Lebanon’s maritime boundaries with Syria have become a popular topic for public discussion of late, and that is a good thing. After all, the more our citizens know, the better-equipped they will be to identify national interests, and therefore to demand that elected officials pursue those interests above all other considerations.

This is only true, though, if the citizens in question have both correct information and a basic understanding of how international relations are conducted. Otherwise they risk being tricked by those actors, both Lebanese and foreigners, intent on furthering their own commercial, diplomatic, geostrategic, personal, and/or political ambitions at the expense of Lebanon’s national priorities.

Anyone seeking to sort out the back-and-forth over this latest chapter of Libano-Syrian relations should keep the following in mind:

– While certain political circles in Lebanon have been estranged from Syria’s current government in recent years, relations between the two countries – not just national and diplomatic, but also economic, social, and family – go back millennia. Whatever disagreements come and go, the relationship is very much a brotherly one within the larger Arab family, and however much they may be at odds with one another, brothers are always there for each other when it matters most.

– Syria is not a party to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). It is, however, both a brotherly country and an observer state, and it should be kept in mind that the standards and practices of UNCLOS have become the norms by which maritime boundary disputes are resolved, whether by treaty, arbitration, or the verdict of a suitable international court.

– The length of the maritime border between Lebanon and Syria is approximately 53 nautical miles; between Lebanon and Cyprus, approximately 96 nautical miles; and between Lebanon and Israel, approximately 71 nautical miles.

In late March, Syrian news outlets reported that a Russian company, Capital Limited, had been contracted by the Syrian government to carry out offshore hydrocarbon exploration and development in Block 1, a parcel of seabed along the country’s maritime border with Lebanon. Almost immediately, certain Lebanese politicians and Arab media sounded alarms to the effect that Syria was infringing Lebanon’s rights, but what is certain is that Block 1 is located in the 100% neutral temporary natural line neutral, according to UNCLOS rules. However, according to global exploration information on global oil and gas concession areas for 2018, 2019, and 2021, and as expected by oil industry specialists, the Syrian blocks have not changed: they have the same dimensions and positions as when they were announced by the Syrian government.

– According to the UN Table of Claims for 2011, Syria’s legal maritime claims are as follows:

Territorial sea = 12 nautical miles

Adjacent areas = 24 nautical miles

Exclusive Economic Zone = 200 nautical miles

– If we look at the Lebanese blocks, we find that they also overlap with the Syrian blocks.

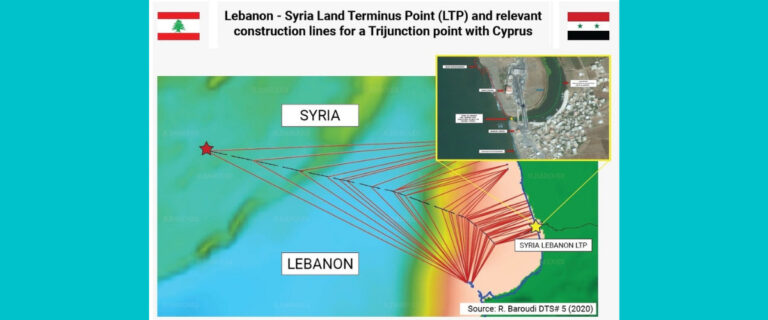

– Over the years, Lebanon and Syria have signed approximately 40 reciprocal agreements in various fields, including some related to the sharing of river waters common to the two countries, including the Assi (also known as the Orontes, or the Mimas) and the Kbir (also known as the Kbir al-Janoubi, which forms much of the northern border between the two countries. This lands border ends at the spot along the coast where the Kbir empties into the Mediterranean Sea, and where the countries have agreed a Land Terminus Point (LTP) at the mouth of the river, as shown on the accompanying map.

Given all of these facts and the overlap between Syrian and Lebanese claims, and in light of the geographical proximities, the numerous signed conventions between them, and their historically fraternal relations, the two countries could easily draw an equidistant line extending from the LTP to the trijunction with Cyprus, about 53 nautical miles offshore. The Lebanese Armed Forces recently did a tremendous job in a much more challenging task, preparing for and conducting negotiations over the far more contentious southern border with Israel, so reaching a deal with the Syrians should be relatively straightforward for the LAF.

With all due respect to those focused on the maritime border with Syria, given the relative ease with which that deal can be made, the more urgent task right now is to preserve our rights along the southern border with Israel, this by amending Decree No. 6433 of 2011 and submitting the new coordinates, as allowed for by Article 3 of said decree, to the United Nations.

The Lebanese and Syrian governments can quickly solve the maritime border problems as long as the LTP line between the two countries is defined and the islands opposite the two countries are officially and unambiguous. As a bonus, a solution to this issue also could also open the way to a just and speedy demarcation of the boundary with Cyprus.

In the same context, so long as the objective is related to the energy sector, and considering the difficult economic and humanitarian situation facing Lebanon, the concerned Lebanese officials also should negotiate with their Syrian counterparts to quickly reactivate Law No. 509, issued on July 16, 2003, authorizing the conclusion of an agreement to sell gas between Lebanon and Syria. The Lebanese side should communicate with Egypt as well, in order to implement Decree. No. 15,722, issued on November 14, 2005. This decree endorsed a memorandum of cooperation between the Lebanese Ministry of Energy and Water and the Egyptian Ministry of Electricity and Energy authorizing the import of gas from Egypt. These two moves would enable Lebanon to cover at least some of its natural gas needs, whether from Syria or from Egypt via Syria, which would allow the generation of cleaner and more affordable electricity at the Deir al-Ammar power station, which was designed to run on gas but has burned diesel for most of the time since its commissioning in 1998.

In light of the fact that some 2 million displaced Syrians are still sheltering in Lebanon because of the continuing war in their homeland, there is good reason to hope that Damascus might adopt a humanitarian perspective by providing the gas on a grant basis (actual or de facto), which would help the Lebanese gain both savings and sustainability. In this scenario, the Lebanese population would derive all the benefits of the Deir al-Ammar station’s 400-megawatt capacity during a very difficult period, but the Lebanese state would not be pressured to repay, giving it time and space to restore economic and fiscal stability. Some will object that US sanctions on Syria make such a deal impossible, but there is nothing stopping Lebanon from applying for the same kind of humanitarian exemption that Iraq received in order to purchase Iranian oil. All that’s needed is for Lebanon’s most influential politicians to set aside the infighting for the sake of an urgent national need.