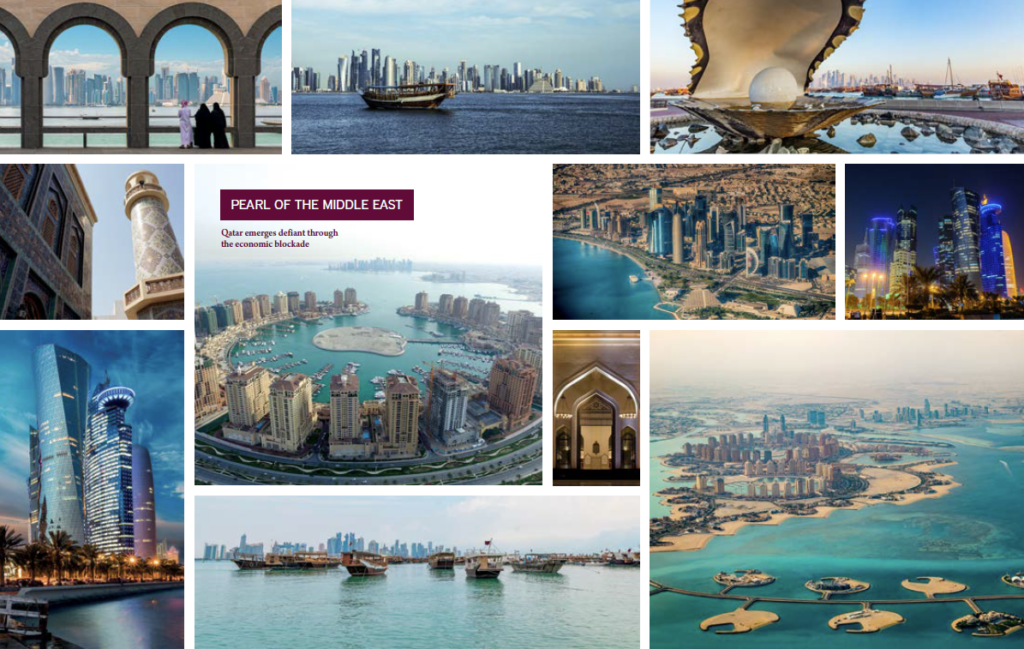

POLITICS / The Qatar crisis is hurting the GCC as a whole, economically and politically, while the targeted country is hanging on / Gerald Butt, Doha

The first time you see the picture, if you arrive in Doha by air, it’s lit up in glass panels above each booth at passport control.

The image is black-and-white—giving the appearance of a stenciled drawing—of the Emir of Qatar, Shaikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani. He looks calm but resolute.

Underneath, the slogan in Arabic reads ‘Tamim the magnificent’. Thereafter, you see the same image all over Doha, sometimes tiny above the lift buttons in office blocks, other times covering the whole side of a high-rise building.

This public display of admiration for Sheikh Tamim, Qataris and long-term expatriates said, reflects genuine feelings of support for the way in which the country’s leader has handled the crisis resulting from the economic blockade. This was imposed by Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Bahrain and Egypt on 5 June. The four states accused Qatar of failing to honour pledges to change

some of its domestic and regional policies.

They insist the siege will continue until,among other things, Qatar ends its alleged support for terrorism and for the Muslim Brotherhood, and shuts down Al-Jazeera television.

Qatar has rejected the conditions as an infringement of its sovereignty. Shaikh Tamim told the United Nations General

Assembly in September that the “unjust” and “illegal” blockade had been imposed “abruptly and without warning”, and Qataris considered it “as a kind of treachery”.

He went on to express “pride in my Qatari people” and foreign residents who had “rejected the dictates” and “insisted

on the independence of Qatar’s sovereign decision”. When he returned to Doha, many thousands of people took to the

streets to welcome him.

The Qatari leadership will have been relieved to witness that degree of public support, because the country faces difficulties—even though the energy sector has been unaffected, with oil and gas exports continuing normally. When the blockade was imposed, Saudi Arabia shut its land border with Qatar. This caused an immediate problem because 40% of Qatar’s food, including milk and dairy produce, came from the kingdom. Within days, new suppliers were found, food was airlifted from Iran and Turkey, and new shipping routes were established, using Sohar and Salalah ports in Oman as hubs, in place of Jebel Ali in the UAE. Food prices have risen, but

today there aren’t shortages.

The siege has, however, disrupted travel. Arriving from destinations to the west of Qatar involves a longer flight over Turkish airspace, swinging south down across Iran before approaching Doha from the east. Qatar Airways is facing higher fuel bills because of this, aside from lost revenue on the dozens of daily flights that used to connect Doha with Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and the UAE. “To get to a meeting

in our Dubai office,” a European businessman in Doha said, “means catching a flight to Kuwait and changing planes there. It’s

the best part of a day.”

Economic survival

The other economic sector hit by the siege is banking. According to economists in Doha, $21bn was withdrawn from Qatari banks in June, as UAE investors and others withdrew deposits, but outflow fell to $10bn in July and $5bn in August. Luiz Pinto, fellow at the Brookings Doha Center think tank and Qatar University, says that “so far, the government has stepped in whenever Qatari banks faced foreign deposit outflows and the non-renewal of other funding arrangements with foreign banks”, mainly with transfers from the country’s sovereign wealth fund, the Qatar Investment Authority.

The blockade, Pinto continued, had inflicted “a shock” on the economy, but in his view “there’s no risk of a Qatari financial collapse. The central bank holds $39bn in international reserves and foreign currency liquidity, and the government holds around $300bn in its sovereign wealth fund. In addition, foreign revenues are firm and the public sector holds $32.4bn, or almost 30% of total deposits, in local currency within the Qatari commercial banking system”.

Pinto also dismisses speculation that Qatar might de-peg its currency from the dollar and devalue, saying that “economic factors commonly associated with a currency crisis and devaluation are simply not found in Qatar. The country runs structurally large fiscal and current account surpluses and is able and willing to sustain the

dollar peg from its vast sovereign wealth”.

There are even outward signs of the economy getting back to normal. The Doha government points to the fact that imports in August were up 40% on July, returning to the pre-embargo level, proving, it says, that new trade channels are in place. But the figures don’t tell the whole story—they tell you the value, not the volume. The country is now compelled to spend more—basic imports are much more expensive. In the weeks ahead things will get more challenging. Qatar’s economy, leaving aside the energy sector, is living off a construction boom, mostly but not totally, associated with preparations for the 2022 World Cup. Almost everything

related to construction is imported, including most of the steel needed. For while Qatar’s own steel industry has the capacity to produce around 80% of its domestic needs, most production is tied

up in long-term export deals. Machinery is the crunch Most importantly, nearly half of all imports are made up of machinery and

precision engineering equipment. This has traditionally been sourced from Jebel Ali, where bulk imports and storage capacity

have kept prices low. Today, industry in Qatar must re-order and bring equipment through Sohar, where there are very long

delays, or direct from the manufacturers in Europe, the US or Far East. Not only will the costs soar with either option, but in

many cases new machinery on order will have different specifications, necessitating the expense of fresh designs and alterations to building plans.

In the short term, priority will be given to imports for the energy sector and for projects directly related to the World Cup. But private firms, which began ventures at a time when there was plenty of cash, could be knocking at the government’s door for help if costs rise substantially.

“It’s a horrendous problem if this whole thing doesn’t get sorted out,” said a Qatari businessman.

For now, the Gulf crisis has reached a plateau, with neither side seeking to escalate it. Qatar hasn’t retaliated against those imposing the siege: it’s still pumping around 2bn cubic feet a day of natural

gas to the UAE through the Dolphin pipeline, although plans to increase the flow to 3.5bn cf/d are now on hold. Former energy minister Abdullah al-Attiyah was the architect of most of Qatar’s gas

developments. Today he runs the Abha Foundation in Doha, a think tank that bears his name, and in a statement to Petroleum Economist said: “Despite the blockade, we honour our commitments

and will continue to supply gas to all of our customers. We like to separate business and politics—it’s business as usual

wherever possible.” While the blockade is focused on Qatar, the three Gulf states imposing it are also feeling negative economic effects from trade, travel and tourism disruptions.

But Nader Kabbani, research director at Brookings Doha, says “economic considerations have, so far, not induced the UAE and Saudi Arabia to de-escalate, even when given opportunities to do so. This suggests that the dispute is more about personalities than anything else.”

In other words, it’s largely down to the three powerful young men at the centre of the crisis, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman of Saudi Arabia and Prince Mohammed bin Zaid of the UAE—the instigators of the policy on Qatar—on the one side; and Shaikh Tamim on the other.

The crisis will continue until they can put aside their personal rivalries. What’s clear already is that the implications for the Gulf Cooperation Council are profound. Even if a solution is found soon, there’s no chance of a return to the status quo ante. The GCC as a body has shown its impotence by sitting on its hands throughout the crisis. Qatar, for example, will never allow a return to a state of affairs in which it relies on its Gulf neighbours for basic imports. Mutual trust has evaporated. This is perhaps the clearest message inherent in the proliferation of black-and-white images of Shaikh

Tamim around Doha.

Qatar’s new national museum, on the southern shore of Doha Bay, is taking shape. Not that it’s an easy shape to describe. The building consists of large, white concrete petals, interlocking at different angles. The design is inspired by what’s known as the desert rose, the effect resulting from the merging of gypsum crystals in the desert producing fragile discs that have the appearance of a petal.

It’s appropriate that the new museum should acknowledge the importance of the desert in the creation of modern-day Qatar: the exploration for oil began in an arid region in the west of the country in the 1930s and subsequent onshore finds provided the revenue to fund the country’s early development. But it’s the sea beyond the line of palm trees outside the nearly-completed national museum—or more precisely the sea-bed—that’s provided the main source of hydrocarbons responsible for Qatar’s explosion of prosperity over the past couple of decades. With its vast offshore North Field (shared with Iran), Qatar sits on the third-largest reserves of natural gas in the world and has become the top producer of liquefied natural gas. Its two LNG firms, Qatargas and RasGas, between them notch up 77m tonnes in output every year.

In 2005, the Qatar government felt that things were perhaps moving too fast and decided to impose a moratorium on further North Field development to allow reservoir studies to be carried out. The energy minister at the time, Abdullah al-Attiyah, said “we have to be very careful about reserves, pressures, and how to continue for as long as we can.” The last LNG venture, Qatargas 4, came on-stream in 2011.

In April this year, the moratorium came to an end. Qatar Petroleum (QP) chief executive Saad al-Kaabi said the company had been “conducting extensive studies and exerting exceptional efforts to assess the North Field, including drilling wells to better estimate its production potential”. As a result, QP had decided that “now is a good time to lift the moratorium”. Work would start on a new venture to produce an extra 2bn cubic feet a day of natural gas for export from a new site in the southern sector of the North Field.

The expectation was that the extra LNG production capacity needed to handle the increased output would be found by the relatively cheap method of debottlenecking the existing trains. At the end of May, QP awarded Japan’s Chiyoda a contract to identify the modifications needed to raise capacity of all the trains at the Ras Laffan LNG plants.

LNG trains ready to launch

Then in July, out of the blue, QP announced that the 2bn cf/d North Field expansion plan was being doubled, and that the country’s LNG output capacity would rise by 30% to reach 100m tonnes a year within five-to-seven years. Petroleum Economist soundings in Doha indicate that Qatar is lining up for a major upstream and downstream gas project that’s estimated to be worth around $30bn. It will involve well drilling, the construction of an offshore receiving platform, the laying of pipes to shore, and the establishment of a new gas treatment plant (with the likelihood of some 24,000 barrels a day of condensate being produced) before the gas reaches the LNG facilities. The debottlenecking is expected to add around 10% to current capacity, taking it up from 77m t/y to about 85m t/y. The expectation at present is that two new LNG trains, each able to produce around 7.5m t/y, will be needed to process all the new gas, with capacity rising to the target 100m t/y.

No timetable has yet been decided for the new venture, but it’s unlikely that QP will reach an agreement with a joint venture partner or partners before the second half of 2018. A huge amount of detail needs to be discussed, not least about the financing of the deal. Given the current constraints resulting from low global oil prices and the economic embargo, QP might want its IOC partner to shoulder the lion’s share of capital expenditure. While the joint venture contract will be open to bidding, there’s a strong possibility that one of the IOCs already involved in Qatargas/RasGas (including ExxonMobil, ConocoPhillips, Shell and Total) will be a favourite. The same goes for firms involved in the construction of the new trains.

Various explanations can be heard in Doha for QP’s decision to double the already announced North Field expansion programme. One is that Qatar is concerned about Iran’s increasing draw-down of gas from its half of the field (which it calls South Pars), another is that Qatar wants to send out a defiant message that it won’t be intimidated by the economic embargo. In the view of Roudi Baroudi, head of Doha-based consultancy Energy & Environment Holding “the North Field has been Qatar’s source of stability, and the country now wants to underpin that stability still more.” Luiz Pinto of Brookings Doha also sees a link with the embargo: “The IOCs and other key foreign investors involved will lobby for international support for Qatar. The projects will also prove to be an additional source of support for the economy in the run-up to the World Cup in 2022.”

After 2022, Qatar alone will bring new output to market—regaining its crown as the world’s leading LNG producer. PE Steady as she goes OIL OUTPUT / Qatar’s oil strategy is to stem further production declines, as it tightens its economic belt and keeps the investment focus on natural gas / Gerald Butt, Doha If a day comes soon, with or without Opec/non-Opec consent, when Gulf oil producers decide to open the taps to the full, Qatar’s contribution won’t make the headlines. Saudi Arabia, with healthy spare capacity, and Kuwait—hopeful of reclaiming its 250,000-barrels a day Neutral Zone half-share and reaching its long-desired 4m b/d capacity target— are the Gulf’s best hopes for adding new crude oil to the market.

Since the discovery and spectacular development of Qatar’s offshore North Field and the country’s meteoric ascent to the peak of liquefied natural gas producers, oil has always been something of a poor relation. In the current climate, with a harsh mixture of relatively low global oil prices and a Qatar economy that’s struggling to come to terms with the Saudi- UAE-led blockade, its status is unlikely to change. Hang on as best you can, seems to be Qatar Petroleum’s (QP) message to the country’s oil sector.

Qatar’s baseline for the Opec/non- Opec cuts was 0.648m b/d, down from peak production of more than 0.73m b/d at the start of this decade. Its current allocation is 0.618m b/d, with actual production in the 0.6m b/d range. “We’ll be quite happy if we can stick with this figure for the immediate future,” an oil sector official in Doha said. “We won’t realistically be expecting more.”

Maintaining the current production level will require enough effort in itself. Nearly half of Qatar’s output comes from the offshore al-Shaheen field, 50 miles (80km) north of Ras Laffan. Up to July this year, Denmark’s Maersk was the operator. The field has now been taken over by the North Oil Company (NOC), a joint venture between France’s Total (30% stake and operator) and QP, (70%).

The concession term is 25 years. Al-Shaheen began production in 1994, and today 300 wells and 30 platforms are in operation. Total’s task, after what’s been a frosty handover from Maersk to NOC, is to expedite the drilling of new wells—the company says it has immediate plans to drill 56, using three rigs—in order to keep al-Shaheen at a 300,000 b/d plateau.

Maintaining a theoretical capacity plateau of 200,000 b/d is also QP’s goal at its vast and veteran (production began in 1949) onshore Dukhan field. At present, output is in the range of around 175,000 b/d. A study for possible enhanced oil recovery operations has been carried out, and the plan is for this to begin in the next two years, QP budgets allowing. But once again, the best hope is for merely a holding operation. There’d been plans for extra barrels to come from the offshore Bul Hanine field, also operated by QP.

A proposal to more than double capacity from 40,000 b/d to 90,000 b/d was announced in May 2014, but dropped when international oil prices fell in the months thereafter. Earlier this year, engineering, procurement and construction bids were received for a Phase 1B development scheme, again with a 90,000 b/d target. But with the economic blockade prompting a reassessment of spending plans, Bul Hanine’s production is unlikely soon to rise above 40,000 b/d. The fate of Qatar’s oil sector, it seems, is to remain for ever in the shadow of big brother gas.