Is Saudi Aramco cooling on crude oil?

Don’t bet on it

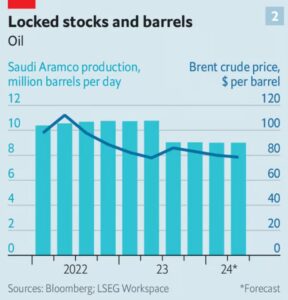

Has saudi arabia stopped believing in a bright future for petroleum? That is the question that in recent weeks has hung over Saudi Aramco. The desert kingdom’s national oil goliath has a central position in the world’s oil markets. Its market value of $2trn, five times that of the second-biggest oil firm, ExxonMobil, and its rich valuation relative to profits are predicated in large part on its bountiful reserves of crude and its peerless ability to tap them cheaply and, as oil goes, cleanly (see chart 1). So Saudi Arabia’s energy ministry stunned many industry-watchers in January by suspending the firm’s long-trumpeted and costly plans for expanding oil-production capacity from 12m to 13m barrels per day (b/d). Was it proof that even the kingpin of oil had finally accepted that oil demand would soon peak and then begin to decline?

To get a hint of Aramco’s answer, all eyes turned to its financial results for 2023, reported on March 10th. No one expected a repeat of the year before, when high oil prices and surging demand propelled Aramco’s annual net profit to $161bn, the highest ever for any listed firm anywhere. But analysts and investors were still keenly interested in the extent of the decline in the company’s revenue and profit, in any changes to its capital-spending plans and, possibly, in the unveiling of an all-new strategy.

In the event, profits did fall sharply, from $161bn in 2022 to $121bn last year, though that was still the second-best performance in the company’s history. Thanks to a recently introduced special dividend, Aramco paid nearly $100bn to shareholders last year, 30% more than amid the bonanza of 2022. It also promised to hand over even more in 2024.

Has saudi arabia stopped believing in a bright future for petroleum? That is the question that in recent weeks has hung over Saudi Aramco. The desert kingdom’s national oil goliath has a central position in the world’s oil markets. Its market value of $2trn, five times that of the second-biggest oil firm, ExxonMobil, and its rich valuation relative to profits are predicated in large part on its bountiful reserves of crude and its peerless ability to tap them cheaply and, as oil goes, cleanly (see chart 1). So Saudi Arabia’s energy ministry stunned many industry-watchers in January by suspending the firm’s long-trumpeted and costly plans for expanding oil-production capacity from 12m to 13m barrels per day (b/d). Was it proof that even the kingpin of oil had finally accepted that oil demand would soon peak and then begin to decline?

image: the economist

To get a hint of Aramco’s answer, all eyes turned to its financial results for 2023, reported on March 10th. No one expected a repeat of the year before, when high oil prices and surging demand propelled Aramco’s annual net profit to $161bn, the highest ever for any listed firm anywhere. But analysts and investors were still keenly interested in the extent of the decline in the company’s revenue and profit, in any changes to its capital-spending plans and, possibly, in the unveiling of an all-new strategy.

In the event, profits did fall sharply, from $161bn in 2022 to $121bn last year, though that was still the second-best performance in the company’s history. Thanks to a recently introduced special dividend, Aramco paid nearly $100bn to shareholders last year, 30% more than amid the bonanza of 2022. It also promised to hand over even more in 2024.

Shovelling a larger chunk of a smaller haul to owners could, on its own, imply that the company is indeed less gung-ho about its oily future. Except that the rich dividend was accompanied by two developments that point in the opposite direction. First, Aramco is rumoured to be preparing a secondary share offering that could raise perhaps $20bn in the coming months—a move typically associated with expansion rather than contraction. Second, even more tangibly, Aramco is already ramping up capital spending.

Its annual results reveal that investments rose from less than $40bn in 2022 to around $50bn last year. In a call with analysts on March 11th Aramco confirmed that the suspension of its planned capacity expansion will save around $40bn in capital spending between now and 2028. But, it added, that does not mean Aramco is not investing. On the contrary, the aim is to spend between $48bn and $58bn in 2025, and maybe more in the few years after that.

A bit of that money will go to clean projects such as hydrogen, carbon capture, renewables and other clean-energy technologies. Some will go to cleanish ones, such as expanding Aramco’s natural-gas production by over 60% from its level of 2021 by 2030, and backing liquefied-natural-gas projects abroad. But most is aimed at ensuring that Aramco can maintain its ability to pump up to 12m b/d of crude.

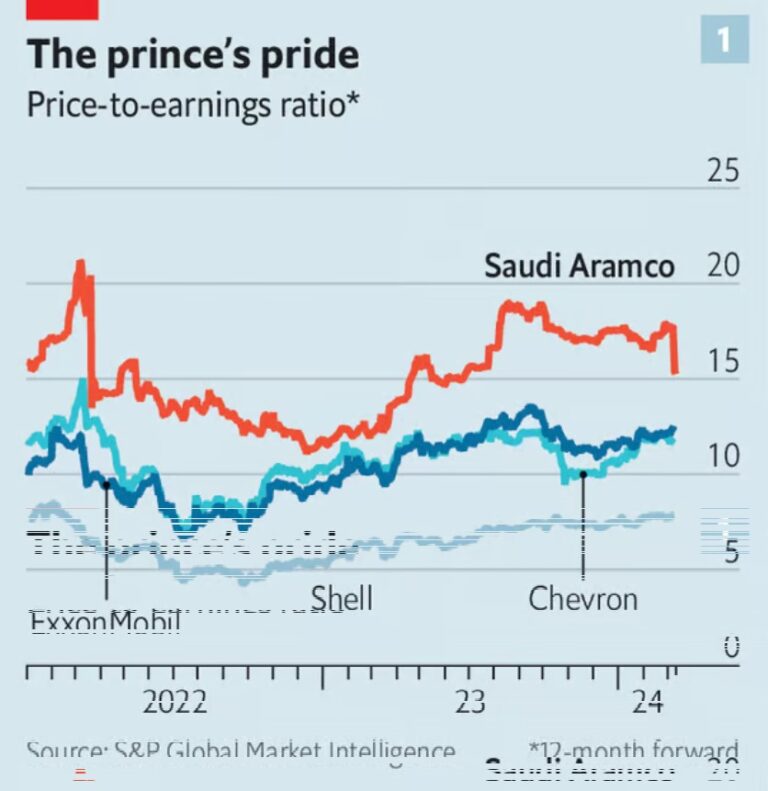

Given the company’s actual output of around 9m b/d (see chart 2), this does not compromise its ability to move markets. If anything, it strengthens Aramco’s position because it implies spare capacity of 3m b/d—above the company’s historic average of 2m-2.5m b/d, according to Wood Mackenzie, a consultancy. The world’s biggest oil firm is, in other words, committed both to pumping oil and to preserving Saudi Arabia’s role as the market’s swing producer.

That is in part because the company is also committed to pumping money into the economic vision for Saudi Arabia championed by Muhammad bin Salman, the kingdom’s crown prince and de facto ruler. This became more evident on March 7th, when Aramco announced the transfer of 8% of its shares, worth $164bn, out of the hands of the government and into the Public Investment Fund (pif), a vehicle for Saudi sovereign wealth which Prince Muhammad has tasked with diversifying the economy. This leaves the pif with 16% of Aramco, compared with the 2% or so that is owned by minority shareholders and traded on the Riyadh stock exchange (the rest remains directly in the government’s hands).

In light of all this, Saudi Arabia’s plans to suspend the expansion of production capacity do not reflect a u-turn away from hydrocarbons. Rather, the pause is born of a hard-headed assessment of market realities: a surge in oil production in the Americas, soft demand in China and cuts to output from the opec cartel (of which Saudi Arabia is the most powerful member). As Amin Nasser, Aramco’s chief executive, summed it up in the results presentation, “Oil and gas will be a key part of the global energy mix for many decades to come, alongside new energy solutions.” And so will Aramco. ■