Globalisation with Chinese characteristics

By Barry Eichengreen/Berkeley

US President Donald Trump’s erratic unilateralism represents nothing less than abdication of global economic and political leadership.

Trump’s withdrawal from the Paris climate agreement, his rejection of the Iran nuclear deal, his tariff war, and his frequent attacks on allies and embrace of adversaries have rapidly turned the United States into an unreliable partner in upholding the international order.

But the administration’s “America First” policies have done more than disqualify the US from global leadership.

They have also created space for other countries to re-shape the international system to their liking.

The influence of China, in particular, is likely to be enhanced.

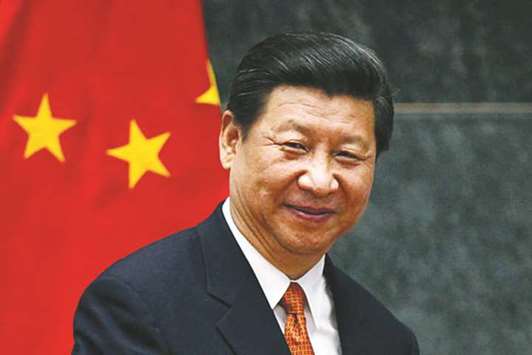

Consider, for example, that if the European Union perceives the US as an unreliable trade partner, it will have a correspondingly stronger incentive to negotiate a trade deal with China on terms acceptable to President Xi Jinping’s government.

More generally, if the US turns its back on the global order, China will be well positioned to take the lead on reforming the rules of international trade and investment.

So the key question facing the world is this: what does China want? What kind of international economic order do its leaders have in mind?

To start, China is likely to remain a proponent of export-led growth.

As Xi put it at Davos in 2017, China is committed “to growing an open global economy.” Xi and his circle obviously will not want to dismantle the global trading system.

But in other respects, globalisation with Chinese characteristics will differ from globalisation as we know it.

Compared to standard post-World War II practice, China relies more on bilateral and regional trade agreements and less on multilateral negotiating rounds.

In 2002, China signed the Framework Agreement on Comprehensive Economic Co-operation with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

It has subsequently negotiated bilateral free-trade agreements with 12 additional countries.

Insofar as China continues to emphasise bilateral agreements over multilateral negotiations, its approach implies a diminished role for the World Trade Organisation (WTO). The Chinese State Council has called for a trade strategy that is “based in China’s periphery, radiates along the Belt and Road, and faces the world.” This suggests that Chinese leaders have in mind a hub-and-spoke system, with China the hub and countries on its periphery the spokes.

Others foresee the emergence of hub-and-spoke trading systems centred on China and also possibly on Europe and the United States – a scenario that becomes more likely as China begins to re-shape the global trading system.

The government may then elaborate other China-centred institutional arrangements to complement its trade strategy.

That process has already begun.

The authorities have established the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, headed by Jin Liqun, as a regional alternative to the World Bank.

The People’s Bank of China has made $500bn of swap lines available to more than 30 central banks, challenging the role of the International Monetary Fund.

Illustrating China’s leverage, in 2016 the state-run China Development Bank and Industrial and Commercial Bank of China provided $900mn of emergency assistance to Pakistan, helping its government avoid, or at least delay, recourse to the IMF.

A China-shaped international system will also attach less weight to intellectual property rights.

While one can imagine the Chinese government’s attitude changing as the country becomes a developer of new technology, the sanctity of private property has always been limited in China’s state socialist system.

Hence intellectual property protections are likely to be weaker than in a US-led international regime.

China’s government seeks to shape its economy through subsidies and directives to state-owned enterprises and others.

Its Made in China 2025 plan to promote the country’s high-tech capabilities is only the latest incarnation of this approach.

The WTO has rules intended to limit subsidies.

A China-shaped trading system would, at a minimum, loosen such constraints.

A China-led international regime would also be less open to inflows of foreign direct investment.

In 2017, China ranked behind only the Philippines, Saudi Arabia, and Indonesia among the 60-plus countries rated by the OECD according to the restrictiveness of their inward FDI regimes.

These restrictions are yet another device designed to give Chinese companies space to develop their technological capabilities.

The government would presumably favour a system that authorises other countries to use such policies.

In this world, US multinationals seeking to operate abroad would face new hurdles.

Finally, China continues to exercise tight control over its financial system, as well as maintaining restrictions on capital inflows and outflows.

While the IMF has recently evinced more sympathy for such controls, a China-led international regime would be even more accommodating of their use.

The result would be additional barriers to US financial institutions seeking to do business internationally.

In sum, while a China-led global economy will remain open to trade, it will be less respectful of US intellectual property, less receptive to US foreign investment, and less accommodating of US exporters and multinationals seeking a level playing field.

This is the opposite of what the Trump administration says it wants.

But it is the system that the administration’s own policies are likely to beget. – Project Syndicate

* Barry Eichengreen is professor of Economics at the University of California, Berkeley, and a former senior policy adviser at the International Monetary Fund. His latest book is The Populist Temptation: Economic Grievance and Political Reaction in the Modern Era.