Germany Set to Draw More Russian Gas, Regardless of What Trump Says

Germany is preparing one of its biggest sustained increases in natural gas consumption in almost two decades, regardless of U.S. admonitions that it shouldn’t draw so much of its energy from Russia.

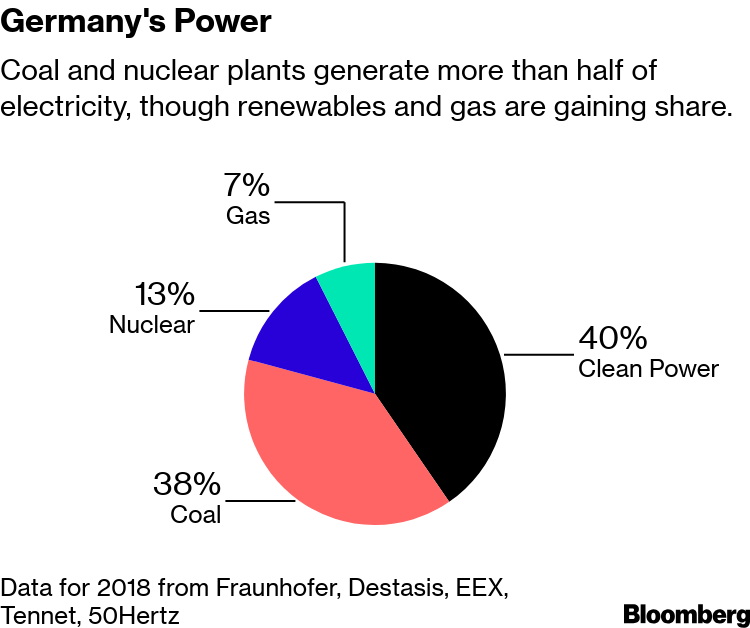

Gas will be one of the main beneficiaries from Chancellor Angela Merkel’s effort to close coal and nuclear plants, which generate half of the nation’s electricity. While the government is seeking to spur renewables, industry executives, energy forecasters and investors say that more gas will be needed to balance the grid when power flows ebb from wind and solar farms.

That outlook helps explain why Merkel is allowing construction of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline from Russia and encouraging new facilities to import liquefied natural gas. In the years ahead, Germany may need much more gas to make up for closing power stations if it falters in its 500 billion-euro ($568 billion) effort to shift toward cleaner fuels.

“Natural gas demand has to go up at least in the short term to make up for the loss of coal,” said Trevor Sikorski, head of natural gas, coal and carbon at Energy Aspects Ltd., an industry consultant in London. “That is probably why Germany’s government is keen for Nord Stream 2.”

There’s a number of issues clouding the outlook for how much new gas Germany will need and when. Those include a lack of clarity on which coal plants will close and when, what restraints the government imposes on the spiraling cost renewables and whether Germany can rely on neighboring nations to make up for temporary shortages on the grid.

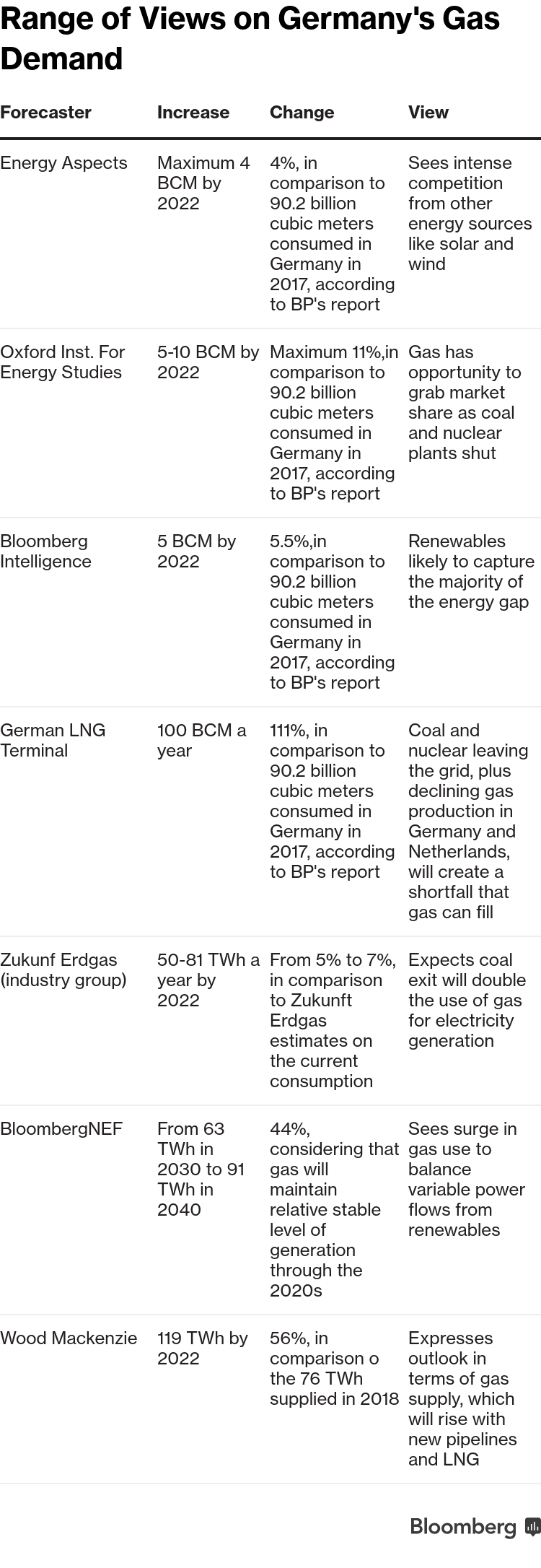

A further complication is the assessment forecasters are making, including differences in their forecasting horizons. Even so, almost all of them are looking for gas demand in Germany to grow — some like Energy Aspects see a few percentage points of expansion and others like the import plant promoter German LNG Terminal anticipate demand doubling.

“It is very much moving to the gas-plus-renewables power future that we advocate as opposed to the coal plus renewables situation,” Steve Hill, executive vice president at Shell Energy, said at an event hosted by the unit of Royal Dutch Shell Plc in London on Feb. 25.

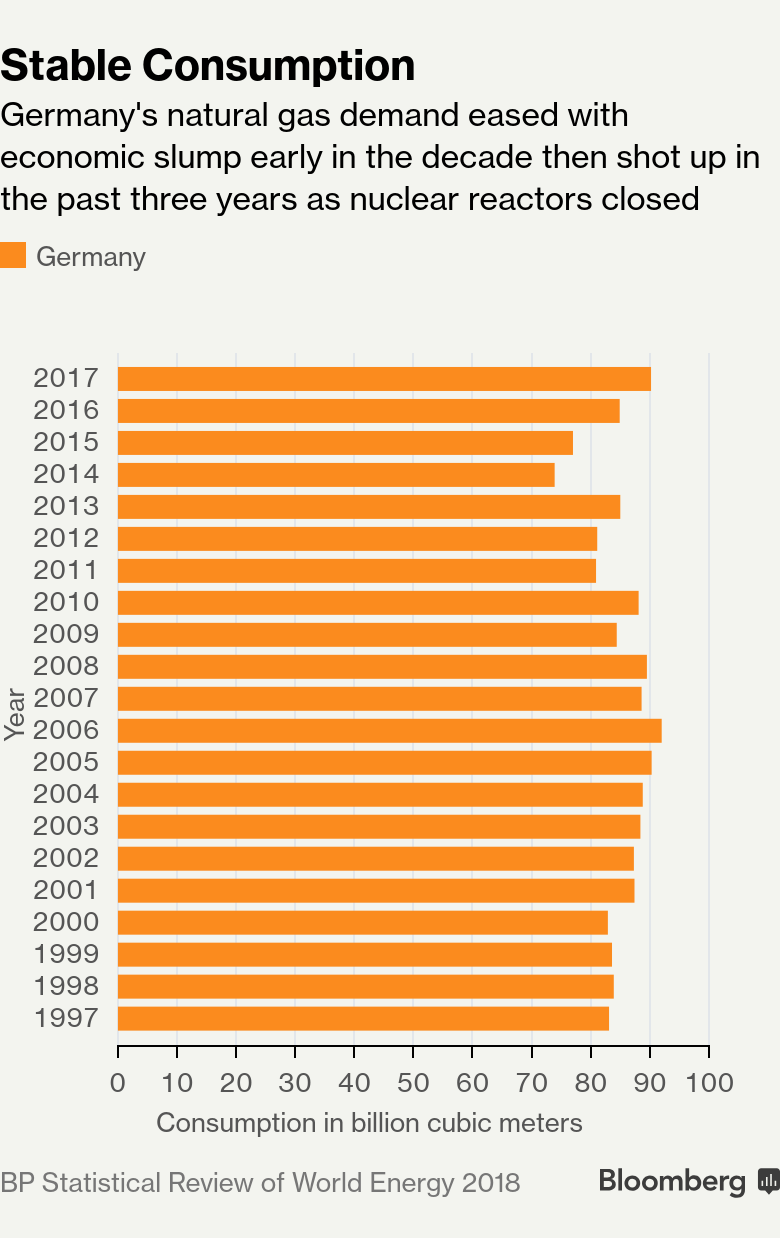

Those forecasts mark a departure from the past two decades, when the solar industry took off and left demand for gas broadly steady. Gas use surged 22 percent in the past three years as atomic sites closed in the wake of the 2011 meltdown at the Fukushima plant in Japan. That largely returned flows to the levels prevailing since 2000, making up for a dip earlier in the decade when the economy slowed.

Now, Germany is starting to think about additional sources of electricity as it winds down its coal plants to meet its climate commitments under the Paris agreement at the same time as it is shuttering the atomic units. While renewables have been gaining rapidly in recent years and will continue to do so, the grid needs a source of supply that can make up for when wind and solar don’t work.

Natural gas is the most obvious choice. It burns cleaner than coal and can feed plants that start and stop when grid dispatchers ask.

“There is certainly more room for natural gas,” said Jean-Baptiste Dubreuil, senior natural gas analyst at the International Energy Agency in Paris. “Coal is baseload, and the question now is to what extend that baseload can be replaced by renewables. Where it is not possible, it will be for gas to step in.”

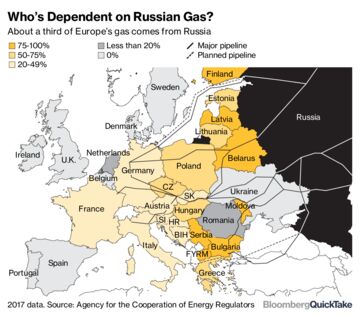

Drawing more gas risks angering the U.S., which wants Germany along with the rest of Europe to develop alternatives to Russian flows. Russia currently feeds a significant share of Germany’s gas needs and is building the Nord Stream 2 pipeline underneath the Baltic Sea to add to the ways it can bring in supply.

The state pipeline champion Gazprom PJSC has been pumping at near record rates into Europe and will bring on that new route as early as the end of this year. Gazprom isn’t the only company gearing up to supply more.

Three German towns — Brunsbuettel, Stade and Wilhelmshaven — are lobbying hard to win federal support to build Germany’s first LNG terminal. That would allow countries from Qatar to Algeria and even the U.S. to send ships with the super-chilled fuel to Germany. And tapping LNG to balance the grid raises separate concerns about security.

“The more Europe bets on LNG, the more dangerous its reliance on imports can get,” said Manfred Leitner, executive board member overseeing downstream at the Austrian oil company OMV AG, which is helping finance the Nord Stream 2 link. “LNG is simply the flexibilization of gas in terms of destination, which means more competition among geographical regions. It is more expensive and less reliable than pipeline natural gas.”

A number of risks could slow or even halt the gas expansion — starting with unseasonably warm weather across the northern hemisphere that depressed demand for heating in Asia and Europe this winter. To refine their forecasts, analysts are watching:

- Whether more homes shift toward gas and away from electricity for heating

- How quickly electric cars spread, which will have a big impact on power demand

- Goals that Germany sets for use of renewables, currently envisioning 65 percent of electricity supply by 2030

- Competition for gas coming from renewables as the cost of wind and solar falls

- Which coal plants close first, since the most polluting units using lignite also are in economically depressed areas where the government needs voter support

- Whether Germany moves to limit gas use either because of pollution or climate concerns