Όπως η Ευρώπη έχει ανάγκη μια ευημερούσα και ενωμένη Κύπρο προκειμένου να ικανοποιήσει τις ενεργειακές της ανάγκες έτσι και η Κύπρος χρειάζεται μια δραστήρια Ευρωπαϊκή Ένωση ώστε να την καθοδηγήσει. Άρθρο του Ρούντι Μπαρούντι ενόψει της Ευρωαραβικής Συνόδου που θα λάβει χώρα την ερχόμενη Τετάρτη στην Αθήνα

Τον ρόλο που μπορεί να παίξει η Ευρωπαϊκή Ένωση για την καλύτερη εκμετάλλευση του φυσικού αερίου που υπάρχει στην Ανατολική Μεσόγειο , τονίζει με άρθρο του στο NEWS 247 ο Διευθύνων σύμβουλος της Ανεξάρτητης εταιρείας του Κατάρ για την ενέργεια και το περιβάλλον. Ο Ρούντι Μπαρούντι* θα είναι μεταξύ των ομιλητών στη Μεγάλη Ευρωαραβική σύνοδο που θα γίνει την επόμενη Τετάρτη στην Αθήνα. Στόχος της συνόδου είναι η ανάδειξη των ευκαιριών για συνεργασία μεταξύ της ΕΕ και του αραβικού κόσμου.

Η Ευρωπαϊκή Ένωση κακοποιείται τις τελευταίες ημέρες, με τα κράτη μέλη και τους πολίτες της να κατηγορούν τις Βρυξέλλες για όλα τα εσωτερικά και διεθνή προβλήματα.

Οι Έλληνες είναι ακόμη έξαλλοι διότι η Ευρωπαϊκή Ένωση βοήθησε να επιβληθούν δρακόντεια μέτρα λιτότητας σε αυτούς με αντάλλαγμα τη συνεχιζόμενη βοήθεια για ανάκαμψη της ελληνικής οικονομίας. Η Ουγγαρία απορρίπτει το δικαίωμα της Ευρωπαϊκής Ένωσης να θεσπίσει μια ενιαία μεταναστευτική πολιτική με ποσοστώσεις και η Μεγάλη Βρετανία όρισε ημερομηνία για την έναρξη της αποχώρησής της από την Ένωση.

Μέρος της κριτικής-οι Βρυξέλλες δεν αποτελούν στόχο, πάρα πολλές αποφάσεις λαμβάνονται από μη εκλεγμένους γραφειοκράτες, μερικοί κανονισμοί χωρίς λόγο ποινοικοποιούν τις μικρές επιχειρήσεις κτλ-μπορεί να είναι εν μέρει αληθής, παρόλο που η συμμετοχή της Ένωσης σε τόσους τομείς της σύγχρονης ζωής μπορεί να αποτελεί έναν υπερβολικά βολικό αποδιοπομπαίο τράγο.

Αντί να επικεντρωνόμαστε αποκλειστικά στις λίγες και σχετικά μικρές αδυναμίες της Ευρωπαϊκής Ένωσης, θα ήταν καλό να κρατήσουμε στο μυαλό μας μόνο τα θετικά.

Στο κάτω-κάτω η περίοδος μετά τη Συνθήκη της Ρώμης που τέθηκε σε ισχύ το 1958 έφερε ένα επίπεδο ευημερίας και ειρήνης που θα ήταν άγνωστο κατά τη διάρκεια προηγούμενης περιόδου της Ευρωπαϊκής Ιστορίας.

Ακόμη και σήμερα καθώς η Ευρωπαϊκή Ένωση και τα κράτη-μέλη έχουν καταπιαστεί με μια ετοιμοθάνατη ανάπτυξη, υψηλή ανεργία και την αναζωπύρωση του εθνικισμού που τροφοδοτούνται από τη χειρότερη παγκόσμια οικονομική κρίση μετά τη Μεγάλη Ύφεση, οι Βρυξέλλες παραμένουν έναν πολύ σημαντικό εταίρο-και συχνά μια κινητήριος δύναμη σε αξιόλογες και απαραίτητες διαδικασίες, ακόμη και πέρα από την ήπειρο.

Πουθενά δεν είναι αυτό πιο αληθινό από ότι για τη μεσογειακή περιφέρεια της Ευρωπαϊκής Ένωσης, όπου η υποστήριξη για τα κράτη μέλη και τις αλληλεπιδράσεις με τους γείτονές της παρουσιάζουν πολλές προκλήσεις αλλά και προσφέρουν πολλαπλές ευκαιρίες προκειμένου να αλλάξουν τη ροή της ιστορίας προς το καλύτερο.

Η διακήρυξη της Βαρκελώνης το 1995, αντηχεί ακόμη και σήμερα ,διότι, παρόλο που η Ένωση για τη Μεσόγειο εξακολουθεί να εξελίσσεται, η Ευρωπαϊκή Ένωση παρέχει ήδη πλατφόρμες για διμερή και πολυμερή συνεργασία, μηχανισμούς για κοινή δράση και πόρους για την υλοποίηση.

Αυτές οι συνεισφορές είναι και θα παραμείνουν ανυπολόγιστης σημασίας για το κοινό μας μέλλον, αν θέλουμε να μεγιστοποιήσουμε τη θετική γεωπολιτική δυναμική, τον τομέα της ενέργειας , ιδιαίτερα στη Νοτιοανατολική Μεσόγειο.

Η Διακήρυξη προβλέπει μια νέα εποχή για τα 28 κράτη μέλη της Ευρωπαϊκής Ένωσης και τα 15 κράτη μη μέλη από την περιοχή της Μεσογείου μια εποχή όπου η συνεργασία χτίζεται πάνω σε τρία “καλάθια”: Στην πολιτική και την ασφάλεια, στην οικονομία και στον πολιτισμό.

Η διαδικασία της Βαρκελώνης πυροδότησε την πραγματοποίηση μιας φιλόδοξης ατζέντας που περιλαμβάνει ευρύτερη περιφερειακή σταθερότητα με βάση τις κοινές αξίες ως σημείο εκκίνησης για τη συνεργασία, την προώθηση της δημοκρατίας , του κράτους δικαίου, της χρηστής διακυβέρνησης και τα ανθρώπινα δικαιώματα και την επέκταση αμοιβαίων επωφελών εμπορικών σχέσεων.

Ζήτησε επίσης τη συμπλήρωση της επιρροής των ΗΠΑ στη Μεσόγειο, παρόλο που πρακτικά το ευρωμεσογειακό πρόγραμμα έχει συχνά παίξει ρόλο εξισορρόπησης και παρείχε εναλλακτική ηγεσία σε περιπτώσεις όπου μια αμερικανική παρουσία θα μπορούσε να αποδειχθεί πολύ διαιρετική.

Αυτές οι προσπάθειες έχουν βελτιώσει δραματικά τις διασυνδέσεις μεταξύ της Ευρωπαϊκής Ένωσης και των γειτόνων της και το μέλλον υπόσχεται τη μείωση των μακροχρόνιων εντάσεων μεταξύ των γειτονικών κρατών εκτός Ευρωπαϊκής Ένωσης και την ενδεχόμενη κατασκευή μιας πιο αποδεκτής περιφερειακής τάξης, που θα είναι ασφαλέστερη πιο δυνατή και πιο φιλελεύθερη.

Και χωρίς αυτές τις βελτιωμένες διασυνδέσεις , η κατάσταση των προσφύγων που προσπαθούν να ξεφύγουν από τον πόλεμο στη Συρία θα ήταν ακόμη χειρότερη. Χιλιάδες περισσότεροι θα είχαν πνιγεί στη θάλασσα και η μετανάστευση των επιζώντων σε όλη την ηπειρωτική Ευρώπη θα ήταν ακόμη πιο ανεξέλεγκτη, άνιση και άδικη.

Η απάντηση της Ευρώπης στην προσφυγική κρίση είναι σε πολύ μεγάλο βαθμό σε εξέλιξη και πολλά απομένουν να γίνουν.

Αυτό που έχει ήδη αποδειχθεί όμως είναι ότι ακόμη και εν μέσω έντονων εσωτερικών διαφωνιών για το πως θα προχωρήσουμε, η επιρροή της Ευρωπαϊκής Ένωσης έχει συνδράμει στο να εξασφαλίσει τα μέτρα που απαιτούνται για να εντείνει τις ναυτικές περιπολίες στα παράλια στη Μεσόγειο και να προκαλέσει μια σχετικά αποτελεσματική συνεργασία ανάμεσα στην Ελλάδα και την Τουρκία.

Τώρα δεν είναι η ώρα να αμφισβητηθεί η αξία τέτοιων επιτευγμάτων. Αντίθετα η κατάσταση απαιτεί ακόμη μεγαλύτερη εξάρτηση από την Ευρωπαϊκή Ένωση για να ξεπεράσουμε τα μηδενικού αθροίσματος παιχνίδια και να αρχίσουμε να ψάχνουμε τις win-win ρυθμίσεις του αύριο.

Πουθενά δεν είναι πιο αληθινό αυτό από ότι στην Κύπρο, μια μικρή αλλά σημαντική χώρα λόγω της στρατηγικής της θέσης, δελεαστική λόγω των φυσικών πόρων της και ικανή να τροφοδοτήσει την αναγέννηση της ευρωπαϊκής οικονομίας και να επιδείξει τη δύναμη του διαλόγου και της συμφιλίωσης.

Παρ´όλες αυτές τις δυνατότητες ο κυπριακός λαός θα μπορούσε σίγουρα να χρειαστεί εξωτερική βοήθεια, αν μη τι άλλο επειδή ο διεθνής παράγοντας έχει κάνει πολλά για να τον διαιρέσει.

Πρόσφατα τα Ηνωμένα Έθνη ανέστησαν την ειρηνευτική διαδικασία και στενοί παρατηρητές εκφράζουν ότι μια συμφωνία είναι εφικτή τους επόμενους μήνες αλλά υπάρχουν δύο ζητούμενα.

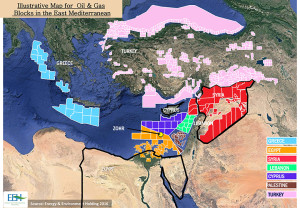

Το πρώτο είναι η πλήρης εκμετάλλευση του ενεργειακού πλούτου. Πρόσφατες μελέτες δείχνουν ότι ο βυθός της Ανατολικής Μεσογείου περιέχει πολύ περισσότερο φυσικό αέριο από ότι πίστευαν στο παρελθόν.

Τόσο η Αίγυπτος όσο και το Ισραήλ, χώρες οι οποίες ήδη έχουν προχωρήσει στην εξόρυξη σημαντικών ποσοτήτων αερίου, έχουν κάνει τεράστιες νέες ανακαλύψεις τα τελευταία χρόνια. Οι τελευταίες έρευνες δείχνουν ότι παρόμοια πλούτη είναι κλειδωμένα κάτω από τις αποκλειστικές οικονομικές ζώνες πολλών άλλων χωρών της περιοχής όπως ο Λίβανος και η Κύπρος.

Ο ρόλος της Κύπρου θα μπορούσε να είναι καθοριστικός διότι εκτός από τις δυνατότητες που έχει με τον ορυκτό της πλούτο, η γεωγραφική και διπλωματική της θέση, της επιτρέπουν να αποτελέσει κόμβο στην ενεργειακή βιομηχανία της Νοτιοανατολικής Μεσογείου.

Η Λευκωσία διατηρεί φιλικούς δεσμούς με πολλές πρωτεύουσες, οι οποίες δεν διατηρούν άριστες σχέσεις μεταξύ τους.

Η θέση της Κύπρου είναι ιδανική για να ξεκινήσει ένας αγωγός προς την ηπειρωτική Ευρώπη και θα μπορούσε να προσφέρει στους γείτονές της την ασφαλέστερη, φθηνότερη και πιο γρήγορη πρόσβαση στη μεγαλύτερη αγορά ενέργειας στον κόσμο.

Για τους ίδιους λόγους , το νησί προσφέρει μια απαράμιλλη ευκολία να είναι περιφερειακή έδρα για τις εταιρείες που ασχολούνται από τις εξορύξεις και τις θαλάσσιες επικοινωνίες μέχρι την παραγωγή, την εμπορία και τη συντήρηση.

Επιπλέον προκειμένου να φτάσει σε αγορές που βρίσκονται ακόμη πιο μακριά και δεν μπορεί να γίνει μέσω αγωγών θα πρέπει να πουλήσει το υγροποιημένο φυσικό αέριο (LNG) και να γίνει η μεταφορά με πλοίο.

Το δεύτερο είναι η συνεχής συμμετοχή της Ευρωπαϊκής Ένωσης προκειμένου να βελτιώσει το πολιτικό περιβάλλον που είναι ευνοϊκό για όλα τα ενδιαφερόμενα μέρη.

Οι λεπτομέρειες ακόμη δεν έχουν σφυρηλατηθεί διότι για να έρθει η ευρωπαϊκή στήριξη θα πρέπει να αποκατασταθεί η εμπιστοσύνη μεταξύ Ελλήνων και Τουρκοκυπρίων.

Η νέα Κύπρος δεν θα προκύψει σε μια νύχτα γι αυτό οι πηγές της Ευρωπαϊκής Ένωσης μπορούν να βοηθήσουν για την επίλυση των διαφορών.

Σε τελική ανάλυση, ακριβώς όπως η Ευρώπη έχει ανάγκη μια ευημερούσα και ενωμένη Κύπρο προκειμένου να ικανοποιήσει τις ενεργειακές της ανάγκες έτσι και η Κύπρος χρειάζεται μια δραστήρια Ευρωπαϊκή Ένωση ώστε να την καθοδηγήσει.

Καμία οντότητα δεν υπήρξε πιο συνδεδεμένη με περισσότερους ανθρώπους σε τόσα πολλά μέση , γεγονός που τα ενδιαφερόμενα μέρη μπορούν να αγνοήσουν μόνο με δική τους ευθύνη.

*Ο Ρούντι Μπαρούντι είναι διευθύνων σύμβουλος της Ανεξάρτητης Συμβουλευτικής εταιρείας του Κατάρ για την Ενέργεια και το περιβάλλον