DOHA: For months, Lebanon and Israel have been at a historic crossroads over how to settle their maritime boundary dispute. Although their competing claims concern a patch of water of less than 900 square kilometers, it is the potential reserves of oil and, especially, natural gas worth billions of dollars that are at the heart of the dispute.

Now both sides acknowledge that US-led efforts to settle the matter diplomatically are still underway. Given the fact that that the two sides do not have diplomatic relations and have been, legally speaking, at war since 1948, resolving this dispute was always going to be a challenge. But it is not impossible. Even if no direct talks can take place between the two countries, both international law, in general, and those associated with the United Nations, in particular, feature institutions, procedures, legal standards, and mechanisms that could help resolve the dispute.

In addition, if attempts to find a solution enjoy the active support and participation of the United States, the UN, and the international community in general, and if the parties are patient, there is a very real chance of success. Significantly, too, as members of the United Nations, both countries have shared obligations under the UN Charter to settle their disputes peacefully and to refrain from the threat or use of force.

Even more crucially, both countries share massive incentives to avoid any kind of action that threatens to upset the development of their respective energy sectors. It is true, as Israeli Energy Minister Yuval Steinitz said recently, that diplomatic negotiations could well delay exploration, delaying Israel’s plans to expand its existing production of natural gas. The same applies for Lebanon’s efforts to get its own energy sector off the ground. But this is insignificant, in the grand scheme of things, compared to the interruptions in gas exploration that could be expected to result from the outbreak of a shooting war, not to mention the direct and indirect costs – in blood and treasure alike – of such a conflict. All told, the drag on the economic prosperity of both countries would outlast the fighting itself as foreign investors and qualified insurers would be spooked for years.

By contrast, if the parties successfully avoid conflict, both of them stand to reap enormous rewards. For Israel, the resolution of the dispute would free it to further expand an industry which is already supplying valuable fuel for power generation and other domestic needs, as well as exporting gas since commencing sales to Jordan earlier this year, and is now gearing up to implement the deal to provide Egypt with some USD 15 billion worth of gas over the next 10 years. This is because opening up the disputed area to exploration and production is likely to enlarge the size of Israel’s gas reserves and revenues. And more importantly, the real prize of resolving the dispute would be an improved risk environment, which would boost the business and investment environments for all Israeli companies, not just energy ones.

For Lebanon, the potential significance of gas exploration and development starting sooner is even greater since none are yet underway. Almost as soon as production were to begin, the national fuel bill would fall substantially, and the state-run Electricité du Liban (EDL) would be able to run some of its generating plants on gas, for which they were designed, rather than the more polluting, more expensive, and less efficient gas oil they currently use. Shortly thereafter, Lebanon’s improved economic prospects – and the reduction in political risks – would lower the cost of credit and make it cheaper to repay its large debt. Eventually, some of the gas produced could even be exported, providing the Lebanese government with new revenues which, if properly managed and invested, could help fight poverty, improve education, infrastructure, and spark a historic socioeconomic rebirth.

For both sides, then, the best way forward is clearly the same: to get rid of the obstacles as quickly and as painlessly as possible, and then get down to business. Since this is a win-win situation, reaching an agreement would be relatively straightforward if we were talking about countries in other parts of the world. We are, however, talking about Lebanon and Israel and the region that surrounds them. And that makes reaching an agreement much more complicated.

This is because some of the obstacles to any sort of Libano-Israeli agreement are effectively insurmountable, at least for the foreseeable future. From this point of view, overcoming the inability to negotiate directly is the easy part as negotiations can be conducted through intermediaries. It will require considerably greater amounts of imagination and dexterity, though, to do so without disturbing the pillars upholding decades of Lebanese foreign policy.

One of these is Beirut’s categorical refusal to recognize Israel because the latter was established at the expense of a brotherly people, namely the Palestinians. Even a Lebanese government inclined to bend on this issue, despite massive internal opposition, would never do so unilaterally for risk of being ostracized by the rest of the Arab world. Let’s not forget that Egypt was shunned for a decade by its Arab League partners for making a separate peace agreement with Israel. Tiny Lebanon would be even more vulnerable to such treatment. It is, in fact, Beirut’s unambiguous stance on Israel which proves it is bona fide and guarantees it a seat in the club of Arab governments. It is proof that, despite having paid a high price compared to other front-line countries, Lebanon will not buckle in its commitment to support the Palestinians. It will not, cannot, and should not abandon that status for the sake of monetary gain.

In this regard, it is essential to keep in mind that Israel’s foreign policy establishment views the extraction with some degree of acceptance, even if partial and/or informal, as an ever-present objective of any Israeli diplomatic interaction, even if indirect, with any Arab government. In fact, however, there also is a long history of Israeli officials leaking discrete contacts with Arab government officials without mutual consent, thereby embarrassing their interlocutors, erasing any progress achieved and poisoning the well for future dialogue.

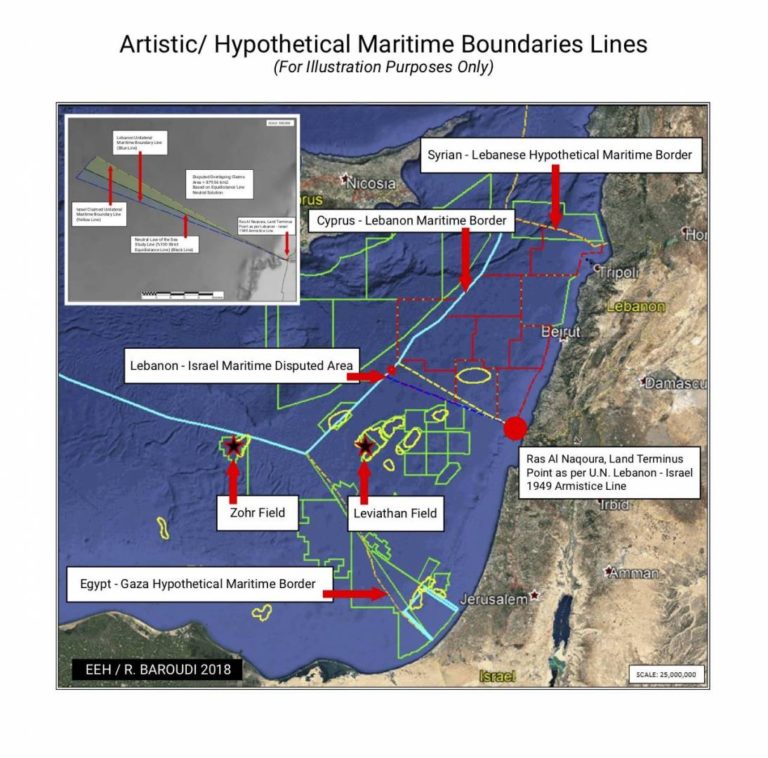

Another obstacle to resolving the maritime dispute is that any solution will almost certainly require Cypriot agreement as its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) abuts that of both countries. Cyprus has signed bilateral EEZ agreements with both countries, although Lebanon has never ratified its agreement with Cyprus. Here arises further complication, given that when Beirut and Nicosia signed their EEZ agreement in 2007, the Lebanese side sought to avoid having the document be viewed as de facto recognition of Israel. Accordingly, and in line with international law on maritime delimitation, the agreement did not define the tri-partite maritime border. Instead, it left the final point in the demarcation of the Cyprus/Lebanese border undefined, with the boundary demarcation coordinates starting at the now almost infamous “Point 1”.

Unfortunately, the approach taken produced the opposite effect because, in the Cyprus-Israel EEZ agreement of 2010, Point 1 was used as the starting point in the demarcation of the Cyprus/Israeli EEZ, even though it clearly should not have been. In this way, the buffer zone which the Lebanese/Cyprus EEZ agreement was meant to establish in order to prevent friction with Israel disappeared. An additional discrepancy on land – with Israel pushing its claim slightly north of the actual border – added to the overlap, but the vast majority is caused by Point 1, which lies some 11 nautical miles (18.5 kilometers) north of where the equidistant point (now known as “Point 23”) among the three countries would be drawn under the terms of Customary International Law (CIL) as set out in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

By agreeing to Point 1 being the starting point of its maritime boundary delimitation, Cyprus breached the express term in its agreement with Lebanon which required it “to notify and consult” Lebanon in case negotiations aimed at the delimitation of its EEZ with a “third country” concerned the demarcation points agreed with Lebanon. Moreover, by doing so, both Cyprus and Israel breached their obligations under UNCLOS and CIL, respectively, to refrain from actions that might prejudice Lebanon’s interests.

Lebanon protested against the terms of the Cyprus-Israel EEZ agreement, officially presenting its claims to the UN and seeking intervention from the Secretary-General and other UN bodies. However, since the Lebanese/Cypriot EEZ agreement never entered into force, arbitration under UNCLOS against Cyprus might be seen as undermining relations with a friendly government, and Israel is not a party to UNCLOS and no third party mechanism has been invoked by Lebanon in respect of this breach.

Commencing conciliation proceedings against Cyprus under UNCLOS seems a more promising route: in this scenario, a conciliation commission would be given twelve months to reach conclusions about the laws and facts of the case, and issue recommendations to help Cyprus and Lebanon agree on a settlement. However, even assuming that the two countries were to accept such findings, the commission would not have the power to determine the tri-partite border and therefore the validity of Israel’s claim to Point 1 being the starting point of the demarcation of the boundary of its EEZ with Cyprus and Lebanon. Given the express wording of the EEZ agreement it signed with Lebanon and its obligations under UNCLOS, it is not clear why Cyprus agreed to Point 1 as the starting point of its boundary demarcation with Israel.

However, the existence of these obstacles does not mean that dialogue is impossible, not when both sides stand to gain so much from a peaceful solution and to lose so much if an armed conflict were to break out, or even if the threat thereof were to persist.

In this respect, despite the contentious nature of its scope, the following provisions of the Israel-Cyprus EEZ agreement point to a way for dialogue to commence. First, Article 1 confirms that the Israel-Cyprus agreement is based on the same British Admiralty map referred to in both the unratified Lebanon-Cyprus EEZ agreement and the Cyprus/Egypt EEZ agreement. Second, Article 1(e) expressly acknowledges that the agreement is to be reviewed and modified if necessary to reach a tripartite agreement on EEZ delimitation among Israel, Lebanon, and Cyprus ( even though the agreement does not refer to Lebanon by name). Finally, most supportive of Lebanon’s claims is the fact that the preamble expressly refers to the provisions of UNCLOS concerning EEZ and the rules and principles of international law of the sea applicable to the EEZ as bases for drawing up the agreement, Article 1(e) refers to CIL principles concerning maritime delimitation and Article 1(b) and Article 1(c) refers to the median line being the basis on which the EEZ was delimited between Israel and Cyprus. These references by Israel to the provisions of UNCLOS regarding EEZ delimitation make it very hard for it to deny that these provisions are principles of customary international law to which it is bound despite not being party to UNCLOS.

As such, from an international law perspective, the basis for the claims made by the two countries are not so far apart and there are mechanisms which have been adopted around the world in similar circumstances which could be invoked to resolve the dispute.

Since neither Lebanon nor Israel has accepted the compulsory jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague, they would need to reach a special agreement to refer the maritime boundary dispute to it. And since Israel is not a party to UNCLOS, Lebanon cannot force Israel to resolve the maritime boundary dispute via third-party resolution pursuant to its provisions. At the same time, it is important to keep in mind that since the Mediterranean Sea is regarded as a semi-enclosed sea, pursuant to Part IX of UNCLOS (which is also considered part of CIL and as such binding on Israel), both countries are under an express obligation to cooperate in case of a disagreement.

A negotiated solution is within reach if both parties act in good faith, especially since both the Paulet-Newcombe Agreement of 1923 and the Armistice Agreement of 1949 provide clear border demarcation – and both the Lebanon-Cyprus and the Israel-Cyprus EEZ agreements allow for modification. If an EEZ boundary can be agreed, straddling reserves could be shared under the terms of a unitization agreement. If no agreement on delimitation is possible, the two countries could agree to declare the entire disputed area a joint development zone and enter into a joint development agreement along the lines of those adopted by Nigeria and Sao Tome and Principe, or Australia and East Timor, to develop such a zone. There are many models of such agreements which can be explored to find the best solution for this case.

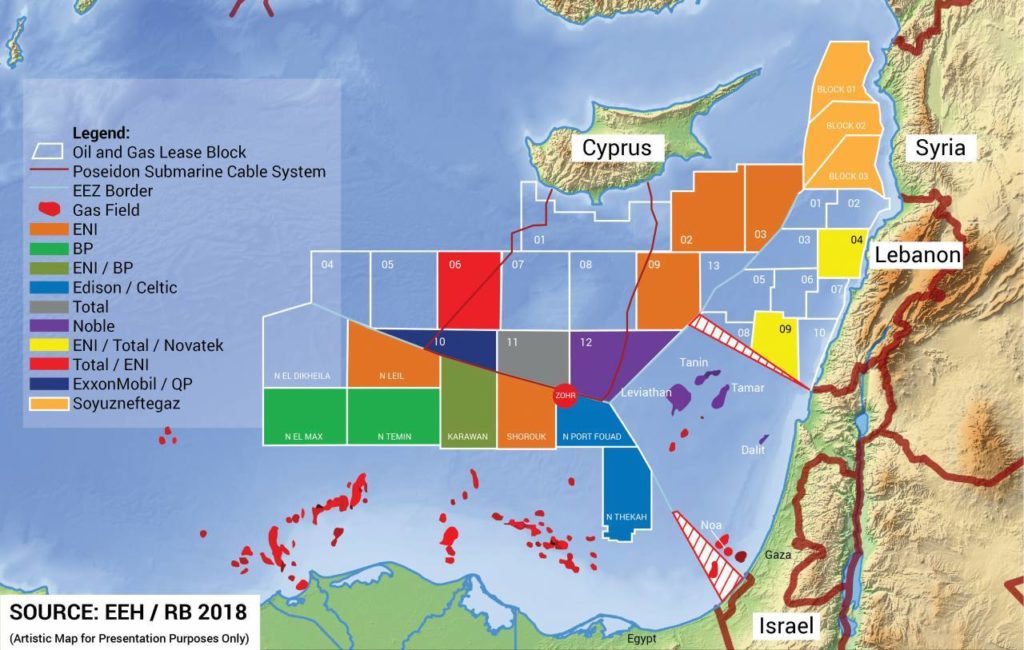

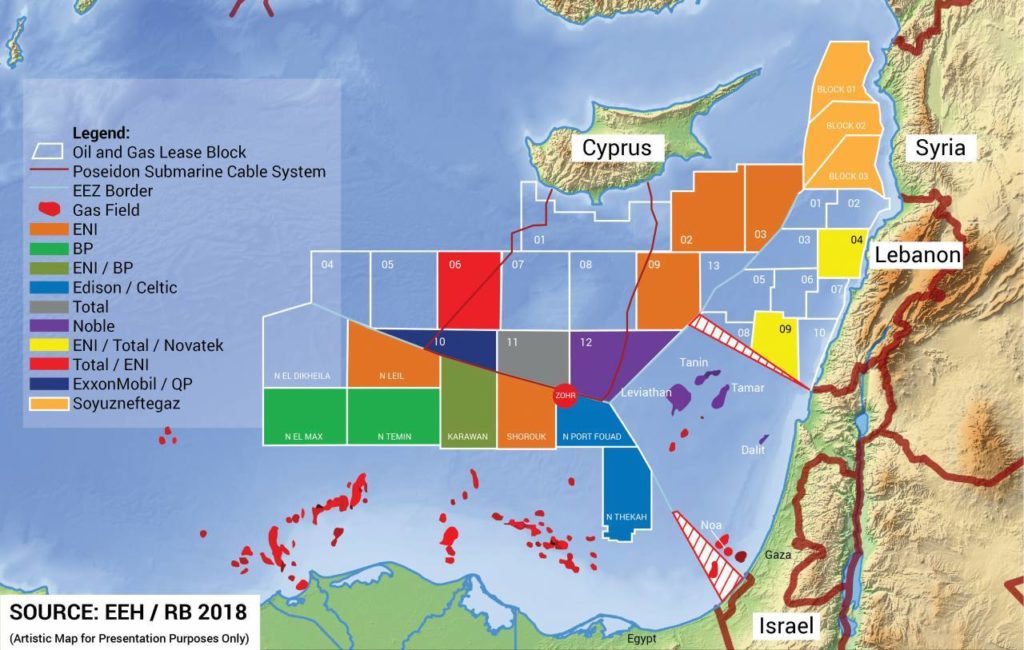

Finally, it is important to note that Israel’s objections to Lebanon having been awarded exploration rights in the “disputed area” are on very thin legal ice. In fact, under UNCLOS and the rules of CIL, Lebanon’s only obligations are to cooperate to reach an agreement through a third party with Israel on the exploration and exploitation of straddling gas reserves; and to, in the absence of such an agreement, exercise restraint with respect to the unilateral exploitation of straddling reserves. Importantly, it has these obligations to the extent that a gas field can be exploited from both sides of the disputed border. Moreover, the obligation to exercise restraint does not apply to granting licenses to explore since no irreparable prejudice would be suffered by Israel by such exploration. Since it would seem that only 8 percent of Block 9 falls in the disputed area and that the actual gas field which Eni, NOVATEK, and TOTAL plan to explore falls outside the disputed area, by allowing such exploration to go ahead Lebanon is not breaching international law.

Despite being in a strong legal position, Lebanon has very little to lose – and everything to gain – by being tireless in seeking a negotiated solution, and the same applies to Israel. Going down the route of a joint development agreement would allow them both to agree to proceed with energy development without sacrificing their long-term interests.

The value of the energy in question has been estimated at more than USD 700 billion; that’s almost three-quarters of a trillion reasons why a solution needs to be found. All Lebanese should want this because it promises, at the very least, to help alleviate so much of the economic/financial pressure that has been holding the whole country back for more than two decades. No opportunity should be lost to state Lebanon’s claim loudly but reasonably, and no effort should be spared to reach an agreement.

Roudi Baroudi is the CEO of Energy and Environment Holding, an independent consultancy based in Doha, and a four decade veteran in the energy industry.