Access to Venezuela’s oil fields fuels Putin’s support for Maduro

Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping have each championed a model of authoritarian capitalism (call it “development with a dictator’s face”). But what neither leader seems to have anticipated is that the Russian and Chinese commercial sectors are becoming political forces in their own right, increasingly bringing pressure to bear on policymaking.

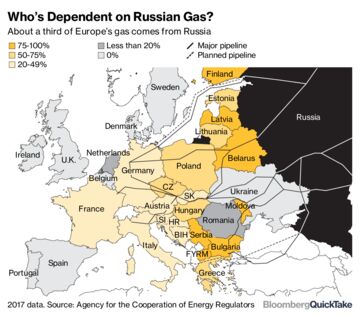

Over the past two decades, Russian and Chinese multinational corporations – many of them awash in cash – have become powerful foreign-policy tools for their respective regimes. But they were once seen as modernising forces that would help open up business and society alike. With energy giants like Gazprom and Rosneft promising to bring commercial values to backward Russia and the newly independent former Soviet states, Anatoly Chubais, a key architect of Russia’s privatisation programme, touted them as the vanguard of a new “liberal empire.” (Insofar as these firms also bound the former Soviet republics closer to Russia, so much the better.)

Likewise, in China during the presidencies of Jiang Zemin (1993-2003) and Hu Jintao (2003-2013), the rise of banks like the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China and the Agricultural Bank of China, and of energy and heavy-industry firms like Sinopec, Sinochem, and the China Railway Construction Corporation, were seen as harbingers of modernisation. Yet today, no one could mistake these firms for the equivalent of an ExxonMobil or a Microsoft. With top executives often parachuting directly into the boardroom from high political office, Chinese mega-corporations have long represented a merger of business and the state.

Moreover, as Gazprom, Rosneft, and the Chinese technology giants ZTE and Huawei have grown more essential to their respective governments, business and state interests have become even harder to disentangle. In the interest of their “national champions,” both the Russian and Chinese governments now seem to be pursuing policies they might not have chosen otherwise.

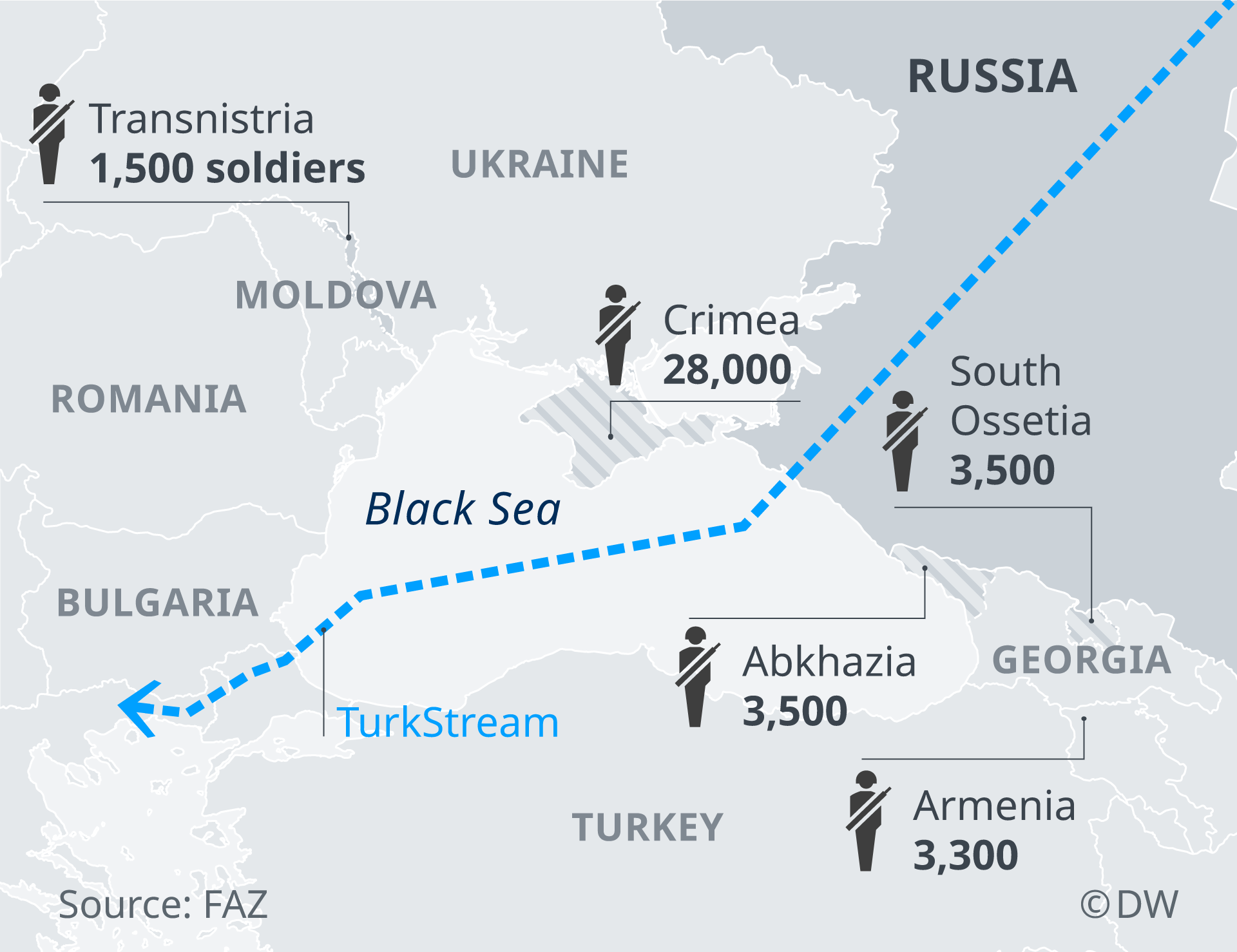

This dynamic is clearly on display in Venezuela. Through its affiliation with Venezuela’s state oil monopoly, Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA), Rosneft has funnelled upward of $17bn in loans to the Chavist regime over the past decade. Meanwhile, Rosneft gained 3mn tonnes of oil in 2017 from its operations in Venezuela; more generally Russia has invested in many Venezuelan industries, from banking to bus assembly. At the same time, Venezuela has been one of the largest buyers of Russian weapons among Latin American countries.

Owing to these debts and other economic ties, Putin has little choice but to back the Venezuelan strongman Nicolás Maduro’s crumbling regime, even as public support in Russia for the Kremlin’s foreign interventions declines. Rosneft’s interests in Venezuela are simply too deep for it to withdraw, especially now that Western sanctions have crippled the firm’s ability to secure financing in international markets.

Russia’s support for Maduro does not rise to the same level as its commitments in Syria, where its relationship with the Assad family goes back decades. Rather, its continued engagement in Venezuela reflects a cold, hard business calculation. According to Reuters, private security contractors with close ties to the Kremlin have been sent to defend Maduro. At the same time, there have been unverified (but plausible) reports of Russian planes departing Venezuela with shipments of gold, as payment for the country’s debts. Putin knows that if National Assembly President Juan Guaidó takes power, those who stood with Maduro will likely be ousted, and Russia’s privileged access to Venezuela’s oil fields revoked.

In monetary terms, Maduro’s fall could mean even larger losses for China, which has investments in Venezuela estimated to be worth around $60bn – at least three times more than Russia’s. Like Russia, China got into bed with the Venezuelan regime in the 2000s, when the country was flourishing under former President Hugo Chávez. While China secured a sorely needed source of oil for its fast-growing economy, Chávez was able to reduce Venezuela’s reliance on the US as one of its leading export markets. In the meantime, Chinese tech giants have aided the Maduro regime in its domestic surveillance efforts, and (like Russia) China has sold Venezuela expensive weapons.

Still, should Maduro fall, China may be less exposed than Russia. The Chinese have been careful to cultivate contacts among various elements of Venezuelan society, including the opposition. And while China still supports Maduro officially, it has not followed Russia in accusing the US of an attempted coup.

This suggests that China wants to avoid the kind of radical steps that Russia is taking. The Kremlin is now actively competing with the US to influence the course of events in Venezuela, and has described the US attempt to deliver humanitarian aid across the Colombia-Venezuela border as a ruse to smuggle in weapons for the opposition.

China’s moderate behaviour no doubt owes something to its ongoing trade negotiations with the US. Before extending his deadline for imposing higher tariffs on Chinese imports, US President Donald Trump indicated that Huawei and ZTE might be included in a final Sino-American trade deal. That would certainly please Xi, whose paramount interest is to protect both firms’ economic might.

With the ability to bar US companies from selling crucial inputs to Chinese firms, the Trump administration could inflict serious harm on both ZTE and Huawei. Huawei already stands accused of conspiring to violate US sanctions on Iran, leading to the arrest of its chief financial officer, Meng Wanzhou, in Canada this past December. And ZTE has pled guilty to similar charges, paying penalties of $1.4bn in 2017.

At the end of the day, Venezuela can’t hold a candle to the strategic importance of these two firms. And for the Kremlin, the calculus is the same: the prerogatives of business define the national interest. But, perhaps to Putin’s chagrin, in Venezuela that calculus has produced the opposite outcome. — Project Syndicate

* Nina L Khrushcheva is Professor of International Affairs at The New School. Her latest book (with Jeffrey Tayler) is In Putin’s Footsteps: Searching for the Soul of an Empire Across Russia’s Eleven Time Zones.