الحدود البحرية لشرق البحر الأبيض المتوسط: حاجة لبنان إلى إكمال ترسيم الحدود البحرية من خلال إبرام إتفاقيات مع قبرص وسوريا – خبير طاقة متخصص

أثينا، اليونان – 25 حزيران 2023: صرّح خبير طاقة إقليمي في مؤتمر عالمي للطاقة في أثينا يوم الأربعاء أنه على لبنان استكمال اتفاقية ترسيم الحدود البحرية مع إسرائيل الموقعة العام الماضي من خلال السعي لاتفاقات مماثلة مع قبرص وسوريا.

إعتبر رودي بارودي، الرئيس التنفيذي لشركة Energy and Environment Holding، وهي شركة استشارية مستقلة مقرها الدوحة، قطر: “يجب أن يتابع لبنان مفاوضات مفتوحة وموضوعية مع هذين الجارين، على لبنان محاورة الدولتين حتى يتم رسم الحدود البحرية بين لبنان وسوريا وقبرص بالكامل وتسويتها رسميًا.”

وفي حديثه إلى الحاضرين من قادة قطاع النفط والغاز وكبار المسؤولين الحكوميين في قمة أثينا للطاقة، أشار بارودي إلى عدة أسباب لإعطاء الأولوية لمثل هذه الاتفاقيات، بما في ذلك حقيقة أن لبنان وسوريا لديهما «مجموعات نفط وغاز بحرية محددة تتداخل بهوامش كبيرة».

وإعتبر أنه «إذا لم يتم تصحيح ذلك، فقد تعني النتائج أن المستثمرين سيبقون بعيدين عن كلا الجانبين، أو سيبطئون في أنشطتهم الاستكشافية، أو حتى أن العلاقات قد تتدهور بين البلدين ». «وان أي من هذه التطورات من شأنه أن يقوض مصالح جميع المعنيين».

وحدّد بارودي ملاحظاته بضرورة التزام الدول الساحلية بسيادة القانون، ولا سيما اتفاقية الأمم المتحدة لقانون البحار (UNCLOS).

وأوضح أن «قواعد اتفاقية الأمم المتحدة لقانون البحار متاحة للجميع، وقد تم تحديد معانيها بشكل أكبر من خلال قرارات المحاكم والتحكيم والمعاهدات الثنائية، والتكنولوجيا المطلوبة لتحديد الحدود العادلة هي في متناول جميع الدول تقريبًا». “ما يعني عملياً أنه يمكن للحكومات أن تعرف مسبقًا ما يمكن أن تدلي به المحكمة أو المحكم حول مطالباتها بالحدود البحرية. طالما أن هناك حسن نية من كلا الجانبين، فإن هذا يبسط العملية بشكل جذري. ”

واردف بارودي إنه بالإضافة إلى حماية مصالحهم الخاصة، فإن لبنان وجيرانه سيضربون أيضًا مثالًا مفيدًا لدول البحر الأبيض المتوسط الأخرى في حل النزاعات الحدودية حبيا.

وأشار على وجه التحديد إلى حالة تركيا واليونان وقبرص، حيث يهدد عدم وجود حدود بحرية تركية – قبرصية وتركية – يونانية مستقرة بعرقلة تنفيذ خط أنابيب مخطط لنقل غاز شرق البحر المتوسط إلى البر الرئيسي الاوروبي. حيث يُنظر إلى هذا المشروع على أنه أمر بالغ الأهمية لخطط أوروبا لاستبدال واردات الطاقة من روسيا، والتي تم تقليصها بشكل حاد منذ غزو الأخيرة لأوكرانيا عام 2022، خصوصا وان الرئيس التنفيذي لشركة الطاقة الإيطالية العملاقة إيني حذر مؤخرًا من أنه لن يمضي قدمًا دون موافقة تركيا.

وقال بارودي «الأتراك واليونانيون والقبارصة يختلفون حول أشياء كثيرة، لكن لديهم أيضًا مصلحة مشتركة في كل من التنمية الاقتصادية، وبالتالي في الاستقرار المطلوب لتسريع هذه التنمية». واضاف في هذا المجال فان « اتفاقية الأمم المتحدة لقانون البحار توفر آلية موثوقة، متجذرة في العلم وتطبيقها القائم على القواعد، يمكن أن توفر الإطار لبدء مناقشة اختلافاته هذه الدول بطريقة خاضعة للرقابة».

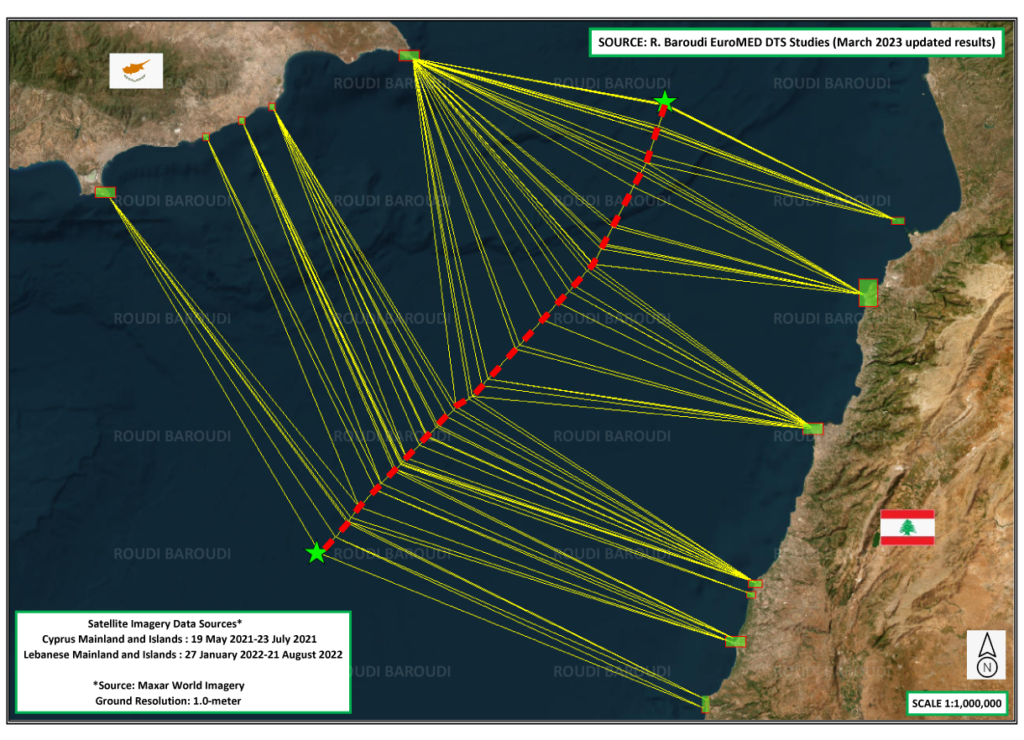

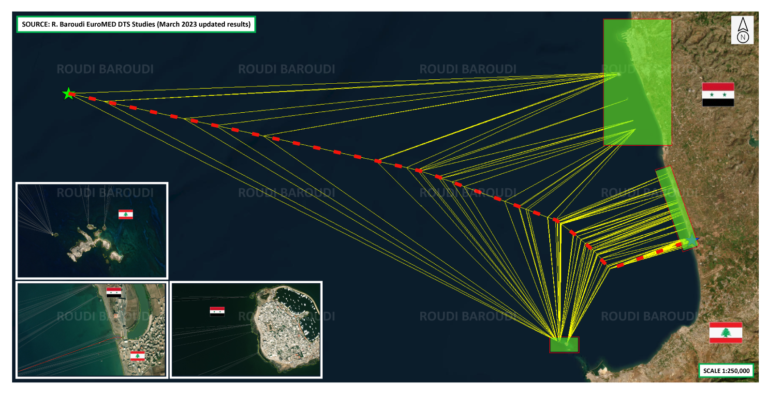

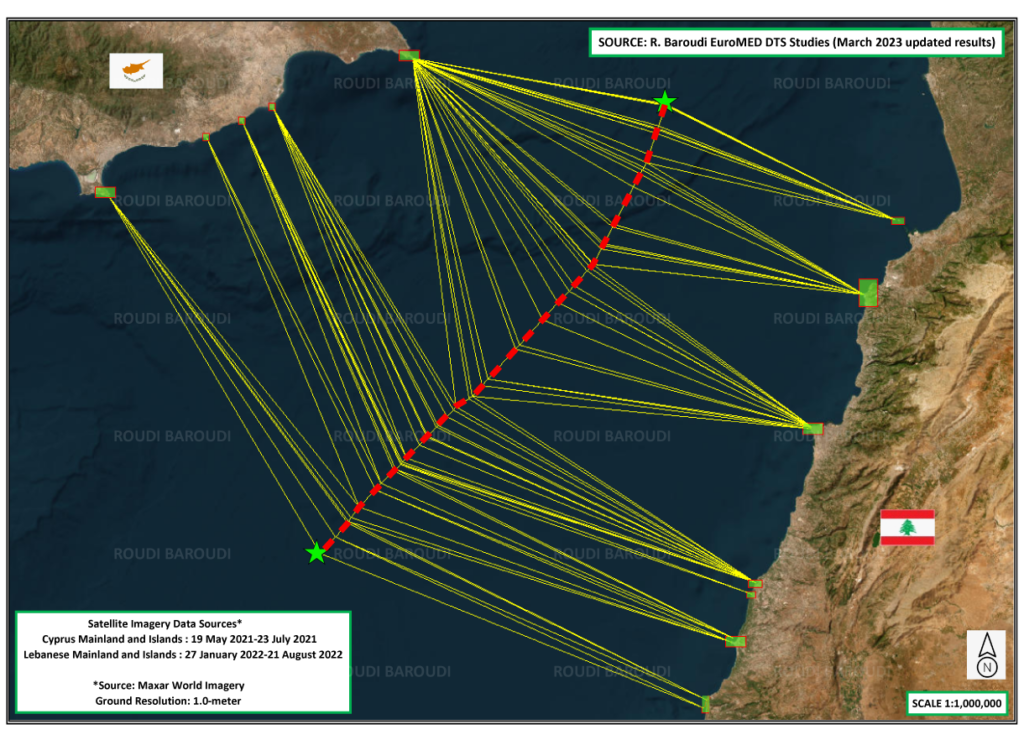

وقد تضمن عرض الدراسة من قبل بارودي أيضًا الكشف عن العديد من الخرائط الحصرية ، بناءً على صور الأقمار الصناعية، والخدمات الجيوتقنية الأخرى. وتشير الخرائط إلى المكان الذي يحتمل أن تحدد فيه الحدود البحرية المقبلة، وفقا للقواعد التي وضعتها اتفاقية الأمم المتحدة لقانون البحار.

رودي بارودي، وهو من المختصين في صناعة الطاقة منذ أربعة عقود ولديه خبرة في كل من القطاعين العام والخاص، هو أيضًا مؤلف العديد من الكتب حول هذا الموضوع، بما في ذلك «النزاعات البحرية في البحر الأبيض المتوسط: الطريق إلى الامام». هذا العمل، الذي نشرته شبكة القيادة عبر الأطلسي في عام 2021، اصاب حينما توقع أنه يمكن حل الاتفاقية اللبنانية الإسرائيلية باستخدام المبادئ التوجيهية لاتفاقية الأمم المتحدة لقانون البحار كنموذج واستخدام حلول غير تقليدية لجوانب معينة من نزاعهما الحدودي.