The World’s Most Important Oil Price Is About to Change for Good

After years of wrangling, the world’s most important oil price is about to be transformed for good, allowing crude supplies from west Texas to help determine the price of millions of barrels a day of petroleum transactions.

The shift is because the existing benchmark, Dated Brent, is slowly running out of tradable oil for it to remain reliable. As such, its publisher S&P Global Commodity Insights — better known by traders as Platts — has been forced to make a dramatic overhaul.

Its switchover was fraught with controversy and caused a lot of stress among physical oil traders. But it was necessary. BP Plc at one stage said that Dated Brent was subject to “increasingly regular dislocations.”

But the future of Dated is now set. From cargoes for June onward, West Texas Intermediate Midland, oil from the Permian will become one of a handful of grades that set the Dated benchmark.

Here’s a look at what matters as the transition gets closer.

1. Why does it matter?

Dated, as it’s commonly known by oil traders, helps to set the price of about two-thirds of the world’s oil and even defines the price of some gas deals.

Oil producing states will often sell their barrels at small premiums or discounts to Dated, so the precise mechanics of how it is formed matter to them. In addition, the benchmark lies at the center of a complex web of derivatives, ultimately shaping Brent oil futures that get traded on exchanges.

Dated affects a host of oil prices, so even crude in Dubai could feel the effects, according to Adi Imsirovic, a veteran oil trader and senior research fellow at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.

2. Exactly what’s happening?

Traders will be able to offer WTI Midland for sale from the US Gulf Coast. It will be delivered into Rotterdam and then price will be netted back using a freight adjustment factor as if it’s shipped from the North Sea.

By following a careful process, Platts will evaluate if the oil is being offered at a higher or lower level than five existing grades that set Dated — Brent, Forties, Oseberg, Ekofisk or Troll.

If Platts judges that WTI Midland is the most competitive price on offer — or actually sold — then it could set Dated.

So WTI Midland might then influence the price a seller of an Atlantic Basin barrel charges a refinery in China.

3. How will price discovery work?

Imagine the existing Dated grades, which go under the acronym BFOET, are at $80 a barrel.

A trader might pick up a cargo of WTI Midland at $79 from a terminal the US Gulf with $2 added delivery cost to Rotterdam — more than 6,000 miles and around 17 days sailing away.

Platts would need to make that delivered cargo like-for-like against the existing BFOET grades, which are transacted on a so-called Free on Board, or FOB, basis in the North Sea.

To do that, it will use what it calls a freight adjustment factor, deducting the estimated cost of transportation across the North Sea to Rotterdam. If that were to be $1 a barrel, then the implied FOB price of WTI Midland in the North Sea would be about $80.

The process will place an emphasis on Platts’s assessments of tanker costs.

4. What’s the timeline?

Some changes are already getting underway. In February, Platts began assessing forward prices based on the new assessment. Real cargoes of crude from the US will be allowed for inclusion from early May.

The expiry of the May Brent futures contract at end-March will rely on some trades of a June Brent exchange of futures for physical contract, which will take the changes into account.

Those key derivatives tools, along with the futures market, will determine the basis price of physical Dated Brent for June.

An important detail in the coming weeks is just how much trading of forward Dated Brent will pick up. So far, twelve entities have conducted transactions based on the new terms, according to Platts.

Ultimately these deals will define something called the Brent Index, a once-a-month price published by ICE Futures Europe that’s used for the cash settlement of futures.

“Without a forward market, there’s no way to financially settle the ICE Brent contract,” said Kurt Chapman, a veteran oil trader and ex-head of crude at Mercuria Energy Group, who retired in 2018 after almost three decades on the front lines of global oil trading.

5. Will the Dated be better?

Assuming traders take to the adjustments, it will be transformative in terms of the underlying volume of oil that can be transacted.

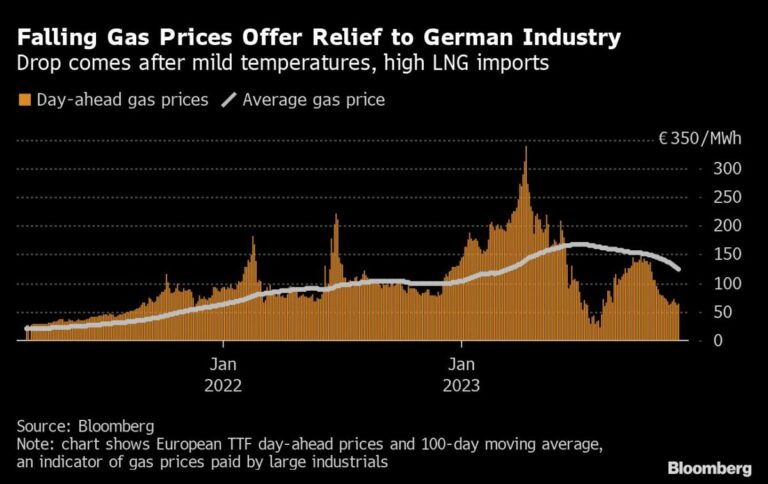

In March alone, around 60 tankers hauling around 1.8 million barrels a day of oil were expected to arrive in Europe, the highest since 2016, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Something like 1 million barrels a day of WTI Midland will theoretically be eligible for inclusion in Dated, although the volumes may be marginal until the trading of new Dated picks up.

6. What are the main concerns?

No two crudes are identical and eventually Platts will have to evaluate precisely how WTI Midland compares with other grades within BFOET.

Some say it is superior because of its density and sulfur levels.

However, some European traders have also expressed worries that the properties of WTI Midland cargoes may not match up to what was stipulated when it traded. That’s because WTI is actually a blend of different crudes.

It would be a problem if a cargo of oil — bought or sold with a view to setting a global benchmark underpinning prices globally — were found to have a flaw.

US terminal operators say there’s not much to be concerned about. They say that the 11 terminals approved by Platts that will send crude are all able to assure consistently high quality to suit Dated.

Another issue is the cargo sizes that will be allowed to be included. At 700,000 barrels, they do not match up to the reality of current oil trading of US oil.

There has been a flood of supertankers bringing 2-million-barrel cargoes across the Atlantic. Those wouldn’t qualify for inclusion in setting the Dated.

Finally, the BFOET grades all come with their own loading programs with each consignment given its own unique identifier. That gives traders clear visibility on the supply of oil. That’s not yet the case for WTI Midland and could cause some uncertainty about how many cargoes are being offered.

— With assistance by Sherry Su and Sheela Tobben