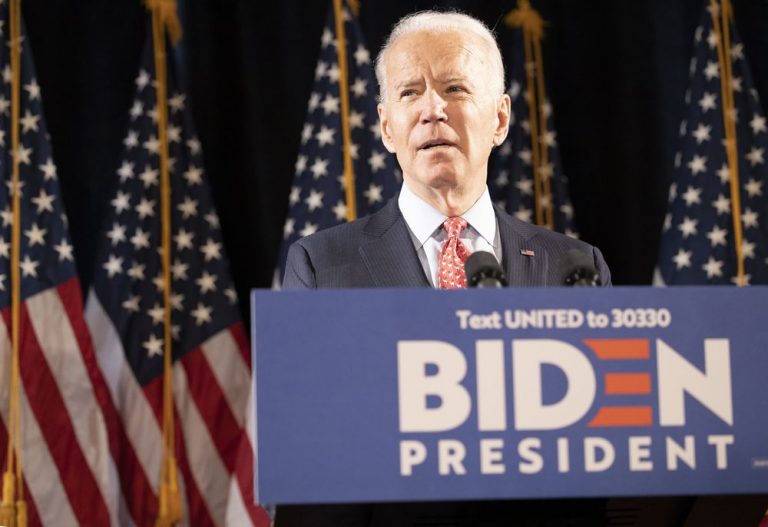

Climate-change activists are pressuring Joe Biden to distance himself from former Obama administration advisers they view as either too moderate or too cozy with the fossil-fuel industry, a sign of disunity on the eve of the Democratic convention.

Groups such as Data for Progress and the Revolving Door Project are building a case against some people advising the Democratic presidential nominee, such as former Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz and President Barack Obama’s environment aide Heather Zichal. Both have served on the boards of companies linked to fossil fuels since leaving government.

The effort reflects simmering tension between the party’s moderate nominee and progressives whose votes he needs to win. Polls show a lack of enthusiasm for Biden among young voters, something that could be exacerbated by open divisions within the environmental movement. But if climate activists succeed in pulling him to the left, it could cost him mainstream support.

The activists are collecting information on the advisers and formulating a strategy that could include a letter-writing campaign and petitions, similar to what has been employed to pressure Biden to sever ties with Obama’s one-time National Economic Council Director Larry Summers. Summers is a contributor to Bloomberg Television.

Obama’s record on cutting greenhouse-gas emissions was widely regarded as ambitious at the time. But activists say now there’s no time left for anything other than a no-holds barred approach.

“If you want to maximize the effectiveness of a Biden administration on climate you need climate warriors,” said Jeff Hauser, founder and director of the Revolving Door Project, which is assembling critical dossiers on the Biden advisers. “If you are going to take the climate crisis seriously you can’t be seeking a middle-road solution.”

Not everyone’s on board with the activists’ approach, with the election quickly approaching. Biden is close to naming a running mate as the party prepares for a trimmed down, four-day nominating convention in Milwaukee set to begin Aug. 17.

Bigger Objective

Some environmentalists prefer to focus on helping Biden defeat President Donald Trump and stop his rollback of environmental regulations. Trump, who is withdrawing the U.S. from the Paris climate treaty, has repeatedly called climate change a “hoax.” By contrast, Biden’s $2 trillion plan for combating climate change won robust praise last month from across the spectrum of environmental advocacy groups.

Others worry that a climate purity test means muzzling some of the nation’s top energy experts.

“It’s OK right now that he’s relying on those people, because he’s got to focus on the primary objective — which is stopping the catastrophe we are in right now,” said Brett Hartl, chief political strategist for the Center for Biological Diversity Action Fund.

But critics say Biden’s reliance on a stable of former Obama energy officials is already limiting the Democratic presidential candidate’s climate ambition.

Read More: Biden Feels Heat From Left to Drop Larry Summers as an Adviser

“The people who built the system and are profiting from it are not going to want to tear it down,” said Collin Rees, a senior campaigner with Oil Change U.S., an environmental group that advocates shifting away from fossil fuels.

Other aides to Obama who have drawn the ire of climate activists include one-time White House energy adviser Jason Bordoff, State Department official Amos Hochstein and economic adviser Brian Deese.

None of the targeted officials are employed by the Biden campaign, though Zichal, Bordoff and Moniz have informally advised it, according to people familiar with the matter who asked not to be identified. And the campaign is widely consulting outsiders; senior campaign officials said they conferred with scientists and leaders of the environmental justice movement in developing Biden’s $2 trillion climate plan.

The activists point to signs of caution, including language in a Biden-Sanders unity task force report that rules out public financing of overseas coal projects but leaves the door open for supporting natural gas ventures.

Obama’s Record

Some environmental activists are advancing an array of choices deemed acceptable as possible cabinet members — from Washington Governor Jay Inslee for Interior secretary to California Air Resources Board Chair Mary Nichols as Environmental Protection Agency administrator.

Biden is naturally relying on advice from some of Obama’s old hands, having worked with many of the same advisers during his eight years as vice president, Hartl said.

Activists say they are most concerned by what Biden’s team has done in recent years — not the policies they pushed as part of the Obama administration.

“We are gearing up,” said RL Miller, chair of California Democratic Party’s environmental caucus and a member-elect to the Democratic National Committee. “We will be exposing the flaws in these people’s records as climate peacocks and we will be making it toxic for Joe Biden to be taking advice on matters of energy from them.”

LNG Exports

Zichal has served on the board of Cheniere Energy Inc., which became the first major U.S. exporter of shale gas in 2016, and has stressed the need to find a “middle ground” environmental policy. She also continues to promote marine protections and sustainability as head of the Blue Prosperity Coalition, has discouraged new offshore drilling off South Africa and previously was vice president of corporate engagement for the Nature Conservancy. Zichal declined to comment.

Bordoff has served on the National Petroleum Council, an Energy Department advisory group that includes oil company executives. He also founded a Columbia University energy policy center affiliated with the School of International Public Affairs Center. It draws funding from oil companies, climate-focused groups and other organizations, including Bloomberg Philanthropies, the charitable organization founded by Michael R. Bloomberg, the majority owner of Bloomberg LP.

Like Summers, Bordoff has praised energy exports, noting earlier this year that increased foreign sales of liquefied natural gas help lower the price of the fossil fuel that can displace dirtier-burning coal in generating electricity. He has also warned about “dwindling time” to make progress fighting climate change and last month argued the issue should be “squarely at the center of U.S. foreign policy.”

Bordoff is helping guide Columbia University’s creation of a climate school and develop a public database with environmental groups to track whether countries are spending Covid-19 recovery dollars to underwrite fossil fuels or clean energy.

“Throughout his career in policy and academia, Jason has focused on the urgency of the climate crisis and worked to achieve more rapid and ambitious action to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050,” said Artealia Gilliard, the Center on Global Energy Policy spokeswoman.

Deep Decarbonization

Moniz, an informal adviser to the Biden campaign, has joined the board of Southern Co., a utility that generates power from natural gas, coal, nuclear and renewables. He also proposed a “Green Real Deal” alternative to the “Green New Deal” backed by progressives. He’s drawn fire for forming a partnership with the AFL-CIO that endorses an “all-of-the-above” climate change strategy.

David Ellis, a spokesman for the Energy Future Initiative, a think tank led by Moniz, declined to comment. But he pointed to testimony Moniz gave earlier this year saying he “endorses a focus on the simultaneous needs for achieving deep decarbonization and ensuring that social equity issues are central in the clean energy transition.”

Hochstein, a former special envoy and coordinator for international affairs under Obama, worked with the State Department to ensure American energy companies had access to global oil fields. More recently, he has warned of the need to stabilize oil-dependent nations as the world moves away from petroleum and has stressed the importance of natural gas in buttressing renewable power.

“I am not advising the Biden campaign, and I fully and 100% support the climate agenda that the campaign has laid out,” Hochstein said.

Deese, an economic adviser to Obama, now works on sustainability issues at investment firm BlackRock Inc. While BlackRock has announced plans to stop investing in companies generating more than a quarter of their profits from coal production, environmentalists say the company hasn’t gone far enough. A BlackRock spokesman said Deese sits on the board of the environmental group League of Conservation Voters and helped negotiate the Paris climate agreement during his time in the Obama administration.

Biden should be getting advice from people who recognize there needs to be an end to fossil fuels instead of embracing “false solutions” that allow the construction of more oil pipelines and gas development for decades to come, said Rees, the Oil Change U.S. official.

“Ten years ago, we were certainly in a different place,” Rees said. “Today, there’s no lack of powerful voices, there’s no lack of people who know their stuff, there’s no excuse for essentially defaulting to energy consultants when you are talking about these kinds of things.”