ترسيم الحدود البحرية اللبنانية – السورية على نار حامية بارودي لـ”النهار”: الحل التقني موجود وينطلق من نقطة الحدود البرّية

وضع لبنان الخطوط الاساسية لبدء عملية التفاوض مع الجانب السوري في ما يتعلق بمسألة ترسيم الحدود، وتحديدا البحرية منها، بعدما أظهر العقد الذي صادقت عليه الحكومة السورية في 18 آذار 2021 والموقع بين وزارة النفط السورية وشركة Capital Limited الروسية للتنقيب عن النفط والغاز شرق المتوسط قبالة ساحل طرطوس، عند الحدود البحرية اللبنانية – السورية، وتحديدا في البلوك البحري الرقم 1 في المنطقة الاقتصادية الخالصة السورية والتي تتداخل مع جزء كبير من المنطقة الاقتصادية البحرية اللبنانية.

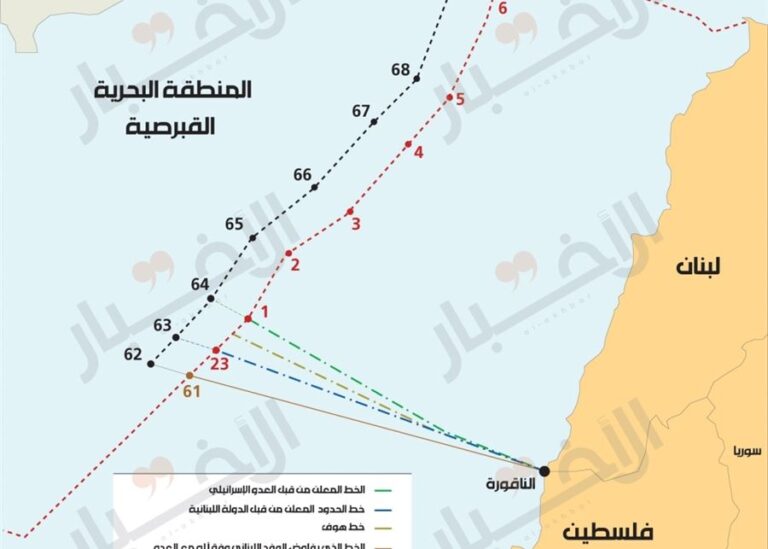

بالفعل، يتداخل البلوك الرقم واحد بشكل كبير مع البلوك 1 والبلوك 2 ضمن المياه اللبنانية، وتراوح مساحة هذه الرقعة المائية ما بين 750 و1000 كلم2 تقريبا داخل المياه اللبنانية إستنادا الى تقارير وضعها الجيش اللبناني، ما أعاد تسليط الضوء على ضرورة الاسراع وفورا بالتفاوض مع الجانب السوري لإنهاء ملف ترسيم الحدود، اقله حاليا الحدود البحرية. هذه الحدود التي كان حددها لبنان في العام 2011 ضمن مرسوم تحديد المنطقة الاقتصادية الخالصة الذي لحظ إحداثيات النقاط الجغرافية للحدود البحرية والبرية، ورفضها الجانب السوري الذي تقدم بشكوى ضد لبنان أمام الأمم المتحدة في العام 2014. إعتمدت سوريا خطاً حدودياً بحرياً ينطلق من شاطئ طرطوس أفقياً نحو الغرب، الامر الذي اعترض عليه لبنان، مؤكدا ان هذه الآلية تتعارض مع قانون البحار الدولي المعمول به من خلال الامم المتحدة والقواعد المعتمدة عالمياً لتحديد الحدود البحرية، وهي ايضا المقاربة التي يعتمدها لبنان في مفاوضاته مع الجانب الاسرائيلي لتحديد حدوده الجنوبية.

البعض طالب الحكومة اللبنانية بضرورة تقديم شكوى ضد سوريا امام الامم المتحدة إعتراضا على آلية ترسيم الحدود البحرية مع لبنان بطريقة أحادية والشروع بأعمال مسح وتنقيب عن النفط والغاز في منطقة متداخلة مع المياه اللبنانية، بعد تقديم اعتراض خطي أمام الحكومة السورية على ما تقوم به والاصرار على وقف الاعمال في المنطقة المتداخلة الى حين الانتهاء من ترسيم الحدود البحرية. ومن المهم أيضا ان تراسل الحكومة اللبنانية ممثلة بوزارة الطاقة والمياه الشركة الروسية المعنية لإعلامها بان الحدود البحرية اللبنانية – السورية غير مرسَّمة نهائيا، وإرسال اي باخرة لتقوم بالمسح الجيولوجي ضمن المناطق المتنازع عليها بين لبنان وسوريا، يعرّض الشركة للملاحقة ويهدد مسار عملها، خصوصا في حال قرر لبنان الذهاب بهذا الملف الى المحاكم الدولية للفصل بالنزاع، وكذلك من المهم ان تطلب الحكومة اللبنانية من شركة Capital الروسية توقيع تعهد لدى الجانب اللبناني بان اي نشاط ستقوم به على البلوك السوري الرقم 1 سيكون خارج المنطقة البحرية المتداخلة بين لبنان وسوريا.

وقد كلف رئيس الجمهورية العماد ميشال عون رئيس الوفد اللبناني المفاوض لترسيم الحدود البحرية الجنوبية العميد الركن الطيار بسام ياسين تسلم زمام التفاوض ايضا مع الجانب السوري في مسألة ترسيم الحدود، على ان يقوم بالتواصل مع الجانب السوري لمعالجة ما يحصل عند الحدود البحرية، والاهم العمل على وقف أعمال الاستكشاف والتنقيب من قِبل الشركة الروسية التى لُزِّمت العمل على البلوك 1 السوري، ضمن منطقة متداخلة مع البلوكات البحرية اللبنانية (1 و 2)، مع الاشارة الى ان طول الحدود البحرية بين سوريا ولبنان يبلغ نحو 53 ميلاً بحرياً، فيما يبلغ طول الحدود البحرية بين لبنان وقبرص 96 ميلاً، وطول الحدود البحرية اللبنانية – الاسرائيلية 71 ميلًا.

في هذا السياق، وانطلاقا من آخر التطورات على صعيد هذا الملف، يعتبر الخبير الدولي في شؤون الطاقة رودي بارودي ان “من المهم التأكيد ان سوريا ليست طرفًا في اتفاقية الأمم المتحدة لقانون البحار ولكنها دولة مراقبة، ومع الإعلان الأخير عن تلزيم البلوك السوري الرقم 1 لشركة “Capital” الروسية برز الكثير من المواقف المتخوفة من التعدي على حقوق لبنان من قِبل سوريا، ولكن ما هو مؤكد ان البلوك السوري الرقم 1 يقع جنوب الخط الطبيعي الموقت المحايد بنسبة 100٪ إذا ما تم اعتماد قواعد الأمم المتحدة لقانون البحار. ومع ذلك، ووفقًا لمعلومات التنقيب العالمية حول مناطق امتياز النفط والغاز لعام 2018 و2019 و2021، لم تتغير اشكال البلوكات السورية، فهي واقعة لم تفاجىء متخصصي الصناعة النفطية، وهي اليوم كما كانت من قبل”. ويشير بارودي الى ان “حدود سوريا القانونية البحرية وفقًا لجدول مطالبات الأمم المتحدة للعام 2011 هي كما يأتي:

البحر الإقليمي = 12 ميلا بحريا.

المنطقة المجاورة = 24 ميلا بحريا.

المنطقة الاقتصادية الخالصة = 200 ميل بحري.

فإذا نظرنا إلى البلوكات اللبنانية، نجد أنها تتداخل أيضًا مع البلوكات السورية”.

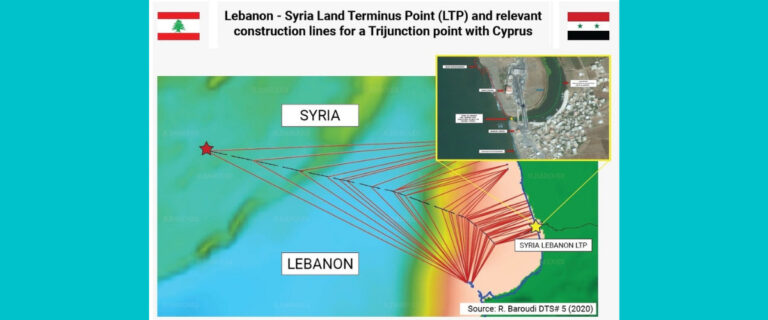

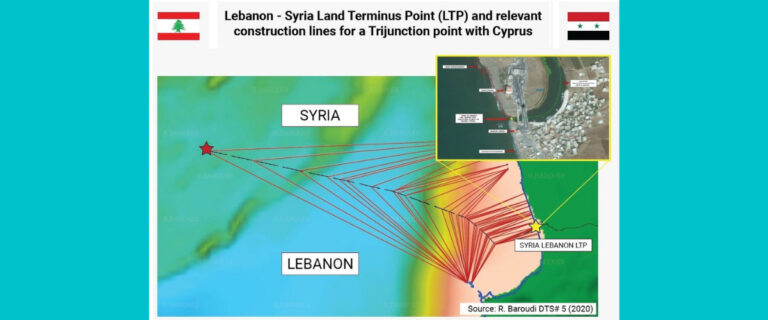

وقّع لبنان وسوريا نحو 40 اتفاقا تتناول مختلف المجالات، ومنها ما يتعلق بتقاسم مياه الانهر المشتركة بين البلدين، سواء نهر العاصي او النهر الكبير الجنوبي. وامام هذه الوقائع ونظرًا للتداخل بين سوريا ولبنان، وعلاقاتهما الجغرافية والمعاهدات الموقعة بينهما، يمكن الدولتين، بحسب بارودي، وبسهولة رسم خط متساوي الأبعاد، وفقًا لنقطة الحدود عند نهاية البر – (LTP Land Terminus Point) الذي يلتزمه كلا البلدين كما هو ظاهر في الخريطة الرقم 1 بحيث يمكن الجيش اللبناني أن يحدد الخط الحدودي بدقة من خلال عمل دقيق ومحترف مع الجانب السوري، شبيه بالذي قام به خلال إعداد المفاوضات لترسيم الحدود البحرية اللبنانية في المناطق المتنازع عليها مع إسرائيل.

تستطيع الحكومتان اللبنانية والسورية حل الاشكال الحدودي البحري بشكل سريع طالما ان خط LTP الذي يعتمد نقطة الحدود على نهاية البر بين البلدين محدد والجزر قبالة البلدين محددة بشكل رسمي لا لبس فيه، وحل هذا الامر يؤسس لحل عادل وسريع لاشكالية ترسيم الحدود البحرية بين لبنان وقبرص نظرا لترابط الملفين. في هذا الاطار وطالما ان الموضوع يتعلق بقطاع الطاقة، ونظرا للوضع الصعب الذي يمر به لبنان من الناحيتين الاقتصادية والانسانية، فانه يتوجب بحسب بارودي على المعنيين اللبنانيين “التفاوض مع الجانب السوري وبشكل سريع لاعادة تفعيل القانون الرقم 509 الصادر في 16/7/2003 والذي يجيز إبرام اتفاقية بيع الغاز بين لبنان وسوريا كما التواصل مع الجانب المصري لتنفيذ المرسوم الرقم 15722 الصادر في 14/11/2005، والذي أجاز بموجب مذكرة التعاون بين وزارة الطاقة في لبنان ووزارة البترول والثروة المعدنية المصرية استجرار الغاز من الجانب المصري، كي يستطيع لبنان ان يؤمن بعض حاجاته من الغاز الطبيعي، ما يساعد على انتاج نظيف للكهرباء وباسعار مقبولة ويحقق وفرا وديمومة. فالجانب السوري يدرك ان هنالك حوالى مليوني لاجئ سوري على الاراضي اللبنانية، وبالتالي في حال تطبيق الاتفاقات المذكورة يمكن تأمين غاز لمعمل دير عمار لكي ينتج اكثر من 400 ميغاواط تساعد كهرباء لبنان في هذه الفترة العصيبة، على ان يدفع لبنان ثمن الغاز في فترة تمتد من ثلاث الى اربع سنوات، وهذا الامر ليس بمستحيل على رغم العقوبات الاميركية على سوريا، اذ ان لبنان يستطيع ان يتشبه بالعراق الذي استطاع ان يؤمن استثناءات انسانية من العقوبات الاميركية المفروضة على إيران عبر محادثات جدية قام بها الجانب العراقي مع الادارة الاميركية، ويعتبر هذا الامر من الضروريات في الوقت الراهن بعيدا من السياسات الداخلية الضيقة التي تمنع القيام بهذه الخطوة المهمة. نجاح هذه الخطوة الوطنية يحتاج، بحسب بارودي، “إلى تعاون وتفهّم كل القوى السياسية اللبنانية لاهميتها في مجال تأمين الطاقة الكهربائية للمواطنين وقطاعات الانتاج اللبنانية التي تعاني الامرّين لتأمين كهرباء باسعار مقبولة للتمكن من الصمود بوجه الازمات التي يمر بها لبنان. فقد بلغت نسبة الفقر بين اللبنانيين نحو 50% وهي نسبة مرتفعة لم يعرفها لبنان من قبل والعدد مرشح للازدياد في حال عدم ايجاد حلول سريعة لما نعاني منه من هدر في مختلف القطاعات، علما ان الكهرباء تقع على رأس القطاعات التي ينبغي اعادة الحيوية اليها وفقا لما جاء في ورقة باريس الاصلاحية ولمطالب صندوق النقد الدولي والمجتمع الدولي لمد يد العون للبنان. واستجرار الغاز الى دير عمار سواء من سوريا او من مصر يساعد على تأمين هذا الامر ولو جزئيا، اذ يؤمن انطلاقا ثابتا ومنافسا للصناعة والزراعة وقطاع الخدمات كما مختلف القطاعات الإنتاجية الاخرى، ما يساعد على تقليل الخسائر التي تعاني منها الخزينة اللبنانية وعلى الحد من استنزاف موجودات مصرف لبنان من العملات الصعبة”.

وينهي بارودي بالتأكيد على “أهمية قيام لبنان بتعديل المرسوم 6433 للعام 2011 والمتعلق بالمنطقة الاقتصادية الخالصة على الحدود الجنوبية، على ان يتم ارسال التعديل الى الامم المتحدة فورا لضمان الحفاظ على حقوقنا البحرية الجنوبية مع اسرائيل”. وحاليا تستمر دراسة التعديلات المقترحة على هذا المرسوم بين الوزارات المعنية وقيادة الجيش، على ان يتم في نهاية المطاف عرضه على رئيس الحكومة لتوقيعه وإحالته على رئاسة الجمهورية لإصدار الموافقة الاستثنائية المطلوبة.