By Roudi Baroudi

Lebanon, Beirut – 07/01/2026

January 1 marked a watershed moment for Cyprus, the first day of a six-month stint in the rotating presidency of the European Union that will give the tiny island nation massive influence, not just over the current agenda, but also the future direction of the entire EU and the destiny of the Eastern Mediterranean region.

The real significance of the moment lay not in the position itself, though, nor even in the considerable (but temporary) increase of Nicosia’s raw political power. In fact, this is not even the first time that Cyprus has held the presidency; that came in the second half of 2012.

Instead, what makes this time different is that a) the Cypriot leadership has laid out a highly ambitious agenda, one designed to generate recurring benefits for both the EU and its Mediterranean neighbors; b) regional circumstances cry out for precisely the kind of engagement that Nicosia envisions; and c) Cyprus today is far better-equipped to advance its politico-diplomatic goals than it was in 2012, not just because its economy and finances are in better shape, but also because it is now on the verge of becoming become an oil and gas producer and exporter. If well-managed, this latter point figures to drive growth for decades to come, enabling historic investments in education, healthcare, transport, and other drivers of greater economic competitiveness and better living standards, not to mention greater ability to influence – and stabilize – the surrounding region.

None of this has happened overnight. Geography and history have situated Cyprus – both literally and figuratively – athwart what is both our planet’s most long-lived maritime trade route and its most famous crossroads of different languages, cultures, faiths, and ethnicities. The island’s copper and other resources have always had their own attractiveness, rising or falling in value depending on the period, but it was location – specifically its proximity to each of Asia, Africa, and Europe – that made Cyprus a strategic prize for millennia, and that same location gives it enormous potential today.

None of this has happened overnight. Geography and history have situated Cyprus – both literally and figuratively – athwart what is both our planet’s most long-lived maritime trade route and its most famous crossroads of different languages, cultures, faiths, and ethnicities. The island’s copper and other resources have always had their own attractiveness, rising or falling in value depending on the period, but it was location – specifically its proximity to each of Asia, Africa, and Europe – that made Cyprus a strategic prize for millennia, and that same location gives it enormous potential today.

For decades, the centerpiece of this toolkit has been a foreign policy which seeks friendly relations with as many countries – especially neighboring ones – as possible. And it has worked. Both during and since the Cold War, for example, Nicosia has been able to maintain working relationships with governments on both sides of the East/West divide, and its search for neutrality has been equally assiduous on the Arab-Israeli front. By habitually staking out the middle ground, Cyprus has not only insulated itself against most external problems, but also steadily burnished its bona fides as a helpful player on the international stage.

All of this helped, but it was not enough. Try as Cyprus might to parlay its neutrality into tangible benefits at home and abroad, its economy remained fragile and unbalanced, distracting and undermining the freedom of action of successive governments. After its banks had to be rescued with EU bailout funds in 2012-2013, support began to grow for reforms that would prevent future meltdowns, restore the stability of the financial services industry, and rebuild its ability to finance private and public activities alike.

By the time President Nikos Christodoulides took office in early 2023, Cypriots of all persuasions were fed up with “business as usual”. Because he had run as an independent and attracted support from a broad cross-section of society, he had a strong mandate to make sweeping changes, and these have included an increase in the minimum wage, income tax cuts for working people, more effective financial regulation, and a far-reaching program for digital transformation. His administration also has run a tight fiscal ship, dramatically reducing public debt (from 115% of GDP in 2020 to a forecast 65% for 2025) and thereby making more credit available to the private sector. As a result, Cyprus’ sovereign rating was upgraded by all three of the major credit rating agencies in 2024, and as of this writing, two of them regard its outlook as positive, while the third views it as stable.

At the same time, Christodoulides’ background as a professional diplomat has empowered him to focus closely and effectively on foreign policy, recognizing its capacity to help shield the island against exogenous shocks, shore up the stability required to pursue its domestic social and economic development goals, and restore regional stability in the aftermath of the war in Gaza. It is no surprise, therefore, that his government has been at the center of international efforts to assist Palestinian refugees affected by the conflict, making Cyprus the staging ground for a vital flow of relief supplies.

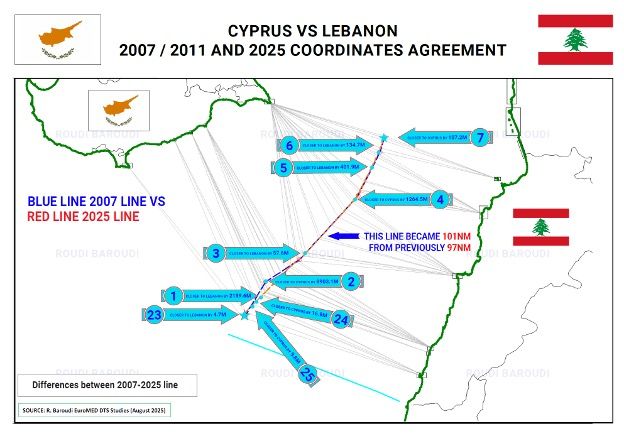

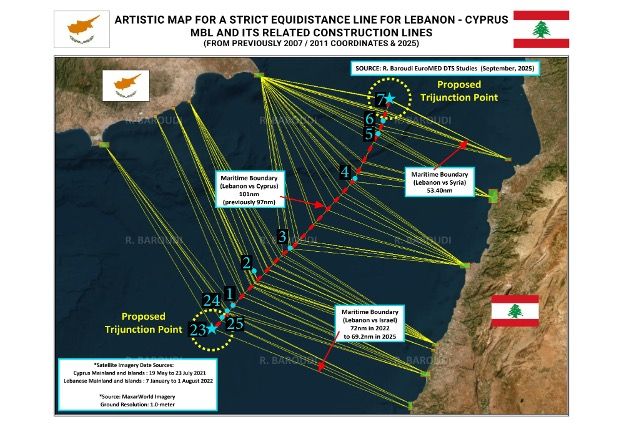

Earlier this year, Christodoulides also teamed up with his Lebanese counterpart, President Joseph Aoun, to make sure their respective negotiating teams finally concluded a long-awaited maritime boundary agreement. The MBA clearly defines who owns what on the seabed, making both countries’ offshore hydrocarbon sectors more attractive, especially to the major oil and gas companies whose capabilities will be required to explore, develop, and extract the resources in question. Nicosia and Beirut are considering several other agreements as well, including ones that would expand cooperation in electricity and other fields, but the MBA was crucial because of the doubts it removed and the doors it opened.

All of these factors are steering the entire Eastern Mediterranean region to what can only be described as its “Cyprus moment”: the day when this miniscule country finally rises to its full stature as an exemplar of effective governance at home and a voice for peace and prosperity abroad. By some measures, this moment has already arrived, but the first exports of Cypriot natural gas to the European mainland will leave no doubt, and those are currently planned for late 2027.

Some say that timeline will be difficult to meet, but the positive effects are already being felt, and historians looking back will rightly regard the precise start state as a footnote. The economy has responded well to treatment, growth is expected to average 3% for the next couple of years, and diversification is already under way, including a variety of technology-related businesses that are helping to reduce the island’s traditional reliance on tourism and construction.

Most importantly, the buzz generated by offshore hydrocarbons has attracted the attention of international investors, and they like what they see: in addition to its prime location and increasingly sophisticated workforce, Cyprus also offers some of the EU’s most favorable tax conditions, strong investment protections, and a common law legal system modeled on the United Kingdom’s, making it more familiar and easier to use for many outsiders. The result? Over the past few years, hundreds of companies have relocated to Cyprus, including some 270 in 2024 alone, adding at least 10,000 new jobs to the island’s economy.

When gas production starts adding extra motive force to the economy, even more opportunities will open up. The advent of domestic energy production will not only spur employment both directly and indirectly, but also reduce the country’s need for expensive energy imports, and put downward pressure on domestic energy prices across the board, imparting a key competitive advantage on the entire economy. If all goes according to plan, this would be just the beginning, because while the savings and security enabled by production will be significant, the really lucrative next step will be exports, and Western Europe – the world’s hungriest energy market – is right next door.

As luck would have it, one of the island’s first commercially operational undersea gas fields figures to be Cronos, which lies within easy distance of existing Egyptian infrastructure, meaning its production can be easily piped to the Egyptian processing facility at Damietta and then delivered to European customers by LNG carrier. Nicosia’s plan is for this flow to begin in 2027, but again, that is just the beginning: Cyprus also expects the nearby Aphrodite field to be a major money spinner, and the plan there is to install a Floating Production Storage and Offloading Unit directly above the deposit. This would enable both dry gas shipments for use in Egypt and further production of LNG for export further afield.

In the longer term, other streams are under consideration as well, including undersea pipelines to Greece, Italy, and/or (one day) even Turkey, and possibly a fully fledged liquefaction plant onshore that would be far and away the largest infrastructure project in Cypriot history. The investments being made and planned now are expected to fundamentally alter the path of Cyprus’ economic and social development. What is more, if and when the time comes, the same infrastructure could also be used to help neighbors like Lebanon and Syria, both of whose coasts are less than 100 nautical miles away, to get their own gas to market. That could be crucial in enabling both of those countries to start recovering and rebuilding after decades of stagnation, and like Cyprus itself, the EU at large has a vested interest in seeing peace and prosperity spread across the Levant.

These and other factors give Cyprus’ strategy a level of importance that goes beyond the purely national. Gas exports to Europe also will help increase the EU’s energy independence, for example, further reducing continuing dependance on Russian energy supplies, and strengthening Europe’s position in any negotiations over the situation in Ukraine. An LNG plant also would make affordable primary energy supplies available to several African countries, enabling them to pursue the electrification strategies they need to modernize their own economies. Again, Europe has countless reasons to want a stabler, happier Africa on its doorstep, beginning with the fact that this would automatically reduce the flow of undocumented migrants making their way across the Med.

The Cypriot approach is nothing less than inspiring, especially since it springs from the very same wells of good will, good governance, and good sense that inspired the Barcelona Declaration more than 30 years ago. The EU envisioned by Barcelona, a strong and cohesive bloc closely integrated with vibrant neighborhoods in the MENA region, has been long-delayed by the collapse of what was then a promising Israeli-Palestinian peace process, and some countries have largely given up on that dream.

Clearly, Cyprus is not one of those countries. Instead, it has wagered on cooperation, weaving good governance and sensible diplomacy into a bold and hopeful venture.

No longer is Cyprus just a sunny little island filled with charming holiday homes and ringed with the Mediterranean’s cleanest beaches; now it is also going to be a regional energy hub, a magnet for international investment, a docking mechanism to help its non-EU neighbors access European markets, and a catalyst for EU dialogue and engagement with Africa and Asia. In short, the country has refashioned itself into the ultimate “project of common interest” – a venture that serves so many useful purposes, both inside and outside the bloc, that it verily demands support from Brussels.

The before and after contrast is increasingly striking. Once a fragile neophyte dependent on handouts from Brussels, today’s Cyprus has transformed itself into the very model of a Euro-Mediterranean country envisioned by the Barcelona process: a hopeful, peaceful, and universally useful land whose success promises only more opportunities for its friends and neighbors.

Cyprus: The Euro-Med region’s ultimate ‘country of common interest’ is about to have its moment