Essar Steel case: SC clears way for ArcelorMittal to complete $5.8 bn deal

US and Chinese trade officials are “close to finalising” some parts of an agreement after high-level telephone discussions yesterday, the US Trade Representative’s office said, adding that deputy-level talks would proceed “continuously.”

In a statement issued after the call, the USTR provided no details on the areas of progress.

“They made headway on specific issues and the two sides are close to finalising some sections of the agreement.

Discussions will go on continuously at the deputy level, and the principals will have another call in the near future,” it said.

The call came as Washington and Beijing are working to agree on the text for a “Phase 1” trade agreement announced by US President Donald Trump on October 11.

Trump has said he hopes to sign the deal with China’s President Xi Jinping next month at a summit in Chile.

Beijing was expected to request cancellation of some planned and existing US tariffs on Chinese imports during the phone call, people briefed on the negotiations told Reuters.

In return, China was expected to pledge to step up its purchases of US agricultural products.

The world’s two largest economies are trying to calm a nearly 16-month trade war that is roiling financial markets, disrupting supply chains and slowing global economic growth.

“They want to make a deal very badly,” Trump told reporters at the White House.”They’re going to be buying much more farm products than anybody thought possible.”

So far, Trump has agreed only to cancel an October 15 increase in tariffs on $250bn in Chinese goods as part of understandings reached on agricultural purchases, increased access to China’s financial services markets, improved protections for intellectual property rights and a currency pact.

But to seal the deal, Beijing is expected to ask Washington to drop its plan to impose tariffs on $156bn worth of Chinese goods, including cell phones, laptop computers and toys, on December 15, two US-based sources told Reuters.

Beijing also is likely to seek removal of 15% tariffs imposed on September 1 on about $125bn of Chinese goods, one of the sources said.

Trump imposed the tariffs in August after a failed round of talks, effectively setting up punitive duties on nearly all of the $550bn in US imports from China.

“The Chinese want to get back to tariffs on just the original $250bn in goods,” the source said.

Derek Scissors, a resident scholar and China expert at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, said the original goal of the early October talks was to finalise a text on intellectual property, agriculture and market access to pave the way for a postponement of the December 15 tariffs.

“It’s odd that (the president) was so upbeat with (Chinese Vice-Premier) Liu He and yet we still don’t have the December 15 tariffs taken off the table,” Scissors said.

US Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin last week said no decisions were made about the December 15 tariffs, but added: “We’ll address that as we continue to have conversations.”

If a text can be sealed, Beijing in return would exempt some US agricultural products from tariffs, including soybeans, wheat and corn, a China-based source told Reuters.

Buyers would be exempt from extra tariffs for future buying and get returns for tariffs they already paid in previous purchases of the products on the list.

But the ultimate amounts of China’s purchases are uncertain.

Trump has touted purchases of $40bn to $50bn annually — far above China’s 2017 purchases of $19.5bn as measured by the American Farm Bureau.

One of the sources briefed on the talks said China’s offer would start at around $20bn in annual purchases, largely restoring the pre-trade-war status quo, but this could rise over time.

Purchases also would depend on market conditions and pricing.

US Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer has emphasised China’s agreement to remove some restrictions on US genetically modified crops and other food safety barriers, which the sources said is significant because it could pave the way for much higher US farm exports to China.

The high-level call came a day after US Vice President Mike Pence railed against China’s trade practices and what he termed construction of a “surveillance state” in a major policy speech.

But Pence left the door open to a trade deal with China, saying Trump wanted a “constructive” relationship with Beijing.

While the US tariffs on Chinese goods has brought China to the negotiating table to address US grievances over its trade practices and intellectual property practices, they have so far failed to lead to significant change in China’s state-led economic model.

The “Phase 1” deal will ease tensions and provide some market stability, but is expected to do little to deal with core US complaints about Chinese theft and forced transfer of American intellectual property and technology.

The intellectual property rights chapter in the agreement largely deals with copyright and trademark issues and pledges to curb technology transfers that Beijing has already put into a new investment law, people familiar with the discussions said.

More difficult issues, including data restrictions, China’s cybersecurity regulations and industrial subsidies will be left for later phases of talks.

But some China trade experts said that a completion of a Phase 1 deal could leave little incentive for China to negotiate further, especially with a US election in 2020.

“US-China talks change very quickly from hot to cold but, the longer it takes to nail down the easy phase 1, the harder it is to imagine a phase 2 breakthrough,” said Scissors. Pages 2, 3 & 12

VERONA/MOSCOW (Reuters) – Russia’s largest oil company Rosneft (ROSN.MM) has fully switched the currency of its contracts to euros from U.S. dollars in a move to shield its transactions from U.S. sanctions, its Chief Executive Igor Sechin said on Thursday.

Rosneft’s switch to the euro is seen as part of Russia’s wider-scale drive to reduce dependence on the dollar, but it is unlikely to quickly boost the euro’s role for Russia given the negative interest rates it carries.

“All our export contracts are already being implemented in euros and the potential for working with the European currency is very high,” Sechin told an economic forum in Italy’s Verona.

“For now, this is a forced measure in order to limit the company from the impact of the U.S. sanctions.”

Reuters reported earlier this month that state-controlled Rosneft set the euro as the default currency for all its new export contracts.

Washington has threatened to impose sanctions on Rosneft over its operations in Venezuela, a move which Rosneft says would be illegal.

Moscow has been hit by a raft of other financial and economic sanctions from Washington over its role in the Ukrainian crisis and alleged meddling in the U.S. elections. Russia denies any wrongdoing.

Last year, Rosneft exported oil and oil products worth 5.7 trillion roubles ($89 billion), according to its reports.

Russia’s largest producer of liquefied natural gas Novatek (NVTK.MM) also said on Thursday it had switched to euros in most of its contracts in order to avoid the impact of U.S. sanctions.

Rosneft’s switch to the euro comes amid attempts by Russian companies to work out ways to carry out international transactions without the U.S. dollar.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has called for de-dollarisation that should help limit exposure to the lasting risk of more U.S. sanctions, while the Russian central bank has lowered the amount of U.S. Treasuries in its reserves in 2018.

The switch to the euro has its downside as, under the current policy of the European Central Bank, financial institutions are required to pay interest for parking excess reserves with the bank, known as negative interest rates.

“There is no sense in storing money under negative interest rates,” said Alexander Losev, head of Sputnik Asset Management.

Given the negative rates, Rosneft’s switch to operations in euros is capable of increasing the amount of euro conversion as Rosneft will seek to ditch the currency for those that are of more use for its operations, market experts say.

The euro’s share in Russia’s exports has been on the rise since 2015 but Rosneft’s adoption of it is unlikely to have an impact on the Russian currency market, said a manager at one of Russia’s state-controlled banks.

Other experts agree, saying that Rosneft will still need to convert its euros for tax payments and other needs in Russia.

A senior forex dealer at a state-controlled bank also said the impact of Rosneft’s move on the rouble will be negligible.

The Moscow Exchange (MOEX.MM) said Rosneft’s move will increase the euro share in its overall trade turnover.

Previously, the share of euro trade on the Moscow Exchange has been increasing only marginally. Over the past year, the euro/rouble share in overall FX turnover on Russia’s main bourse stood at 12%, up from 11% in 2017 and 9% in 2016.

Bloomberg/ Johannesburg

Credit default swaps for Eskom Holdings SOC Ltd, South Africa’s state-owned power company, are trading near the cheapest level in almost three years relative to the sovereign risk after the Treasury published proposed conditions for funds to bail out the utility.

That suggests investors are comfortable a turnaround plan for the debt-ridden company, which President Cyril Ramaphosa says will be presented to cabinet shortly, will include a sustainable framework to deal with its $30bn of debt. The government has said it won’t allow Eskom to fail or bondholders to take a haircut.

“It’s about 10 years too late, but better than nothing,” said Rashaad Tayob, a money manager at Abax Investments Ltd in Cape Town. “It’s positive that there will be oversight on Eskom’s capex, and a requirement that they must work to recover debtors in arrears. But nothing on energy and staff costs, so we must wait for the special paper/white paper to understand the long term plan to fix Eskom.”

Eskom, which supplies about 95% of South Africa’s electricity, has been granted 128bn rand of state bailouts over the next three years to help it remain solvent.

Amounts of 26bn rand and 33bn rand will be allocated in portions to Eskom in the 2020 and 2021 financial years on dates determined by the finance minister, the Treasury said in a presentation on its website Wednesday.

The conditions offered include that Eskom publish separate financial statements for its generation, distribution and transmission units. Treasury will also require daily liquidity position updates and for no incentive bonus payouts to be made to executives in the years where equity support is provided.

“The market is taking comfort from the fact that there is increased government oversight,” said Bronwyn Blood, a fixed-interest portfolio manager at Granate Asset Management Ltd in Cape Town. “Conditions imposed on Eskom will ultimately allow for more certainty around repayment of debt, thus minimising the risk of default.”

MILAN (Reuters) – The chief executive of UniCredit (CRDI.MI) has a plan to revive his company’s ailing share price – make it less Italian.

Italy’s biggest bank is looking at whether it can distance itself from its home country’s stagnating economy and fractious politics by putting some of its most prized assets under one roof in Germany, people familiar with the matter said.

Jean Pierre Mustier will unveil on Dec. 3, as part of his new business plan, a scheme to set up a new sub-holding company in Germany to house the bank’s foreign operations, the sources said.

By keeping its assets in Germany, Austria, Eastern Europe and Turkey away from Italy, UniCredit could reduce their Italian identity – and associated credit rating – making their funding cheaper, the sources said.

Mustier, a Frenchman appointed in July 2016 to reinvigorate the then weakly capitalized Milanese bank, has sold businesses, cut jobs and shut branches to strengthen UniCredit’s balance sheet. Sources earlier this year said the bank had put on ice a possible bid for German rival Commerzbank (CBKG.DE).

But UniCredit, which describes itself as pan-European, operates in 14 countries and makes just over half of revenues outside Italy, is still essentially perceived by investors as a risky Italian institution.

The new plan is an indication of Mustier’s belief that the Italian economy is holding back UniCredit’s share price and risks pushing up the bank’s funding even more if the economic outlook deteriorates.

“Who can say for sure that Italy’s debt won’t be downgraded to junk?” said one source, speaking on condition of anonymity and describing the corporate reorganization as an insurance policy if Italy’s economy continues to perform poorly.

“The bank has to be ready for that kind of possibility,” the person said, noting Moody’s currently rates the euro zone’s third biggest economy – burdened with the second highest debt to GDP ratio in the single currency bloc – just one notch above non-investment grade. Germany has a triple-A rating with all major credit ratings agencies.

Italian banks – which are struggling with bad loans, a sluggish economy and political instability – have traditionally been seen as a proxy for the country’s sovereign debt because they hold vast amounts of government bonds.

UniCredit trades at 0.5 times book value, among the lowest levels in the industry, despite having a better than average return on equity. Its share price has fallen 30% since April last year, wiping out much of the rally it had after Mustier took charge.

To place a $3 billion, five-year bond in November last year, when a sell-off in Italian assets sent borrowing costs for the country’s banks soaring and shut all but the strongest names out of the funding market, UniCredit had to pay a steep 7.8% coupon.

“UniCredit is by size one of Europe’s leading banking groups but, because of its Italian roots, investors associate it with the Italy risk to an extent which is in my opinion excessive given its geographical diversification,” Stefano Caselli, banking and finance professor at Milan’s Bocconi University.

“It’s clear that UniCredit pays a price both in terms of regulatory capital and cost of funding for being Italian,” he said. “So a diversification strategy aimed at allowing the bank to link its cost of funding to the countries where it is present makes total sense.”

Some other Italian companies with big foreign operations, including car maker Fiat Chrysler (FCHA.MI) and broadcaster Mediaset (MS.MI), have moved or are in the process of moving their legal headquarters to the Netherlands as part of a pivot away from Italy.

he European Central Bank would have to approve the plan to set up the holding company in Germany – where UniCredit already owns lender HVB – potentially taking at least a year, meaning the shift would not happen for sometime.

Mustier has repeatedly said that UniCredit will remain listed and headquartered in Milan and reiterated the bank’s commitment to its home country.

But since May he has steadily cut the bank’s exposure to Italy, including by selling its stake in online broker FinecoBank (FBK.MI) and announcing it would reduce its 55 billion euros ($61.37 billion) portfolio of Italian government bonds.

The bank is also considering cutting 10,000 jobs, or around 10% of its workforce, as part of the new 2020-2023 plan, almost all of them in Italy, sources said in July.

UniCredit has said any workforce reduction will be handled through early retirement.

But the planned cuts, together with a wider management reshuffle earlier this year, have helped to create a perception among some employees and rivals that the bank is less focused on its Italian operations.

“You can tell that the Italian commercial business is not a priority for them, they are not aggressive, they are not chasing clients,” said the chief executive of another Italian bank.

A UniCredit spokesperson said that figures from the bank’s divisional database showed customer deposits for Italy’s commercial banking operations rose by 4.3% in the second quarter of 2019 from a year earlier, while customer loans increased by 1.7% over the same period.

Explore what’s moving the global economy in the new season of the Stephanomics podcast. Subscribe via Pocket Cast or iTunes.

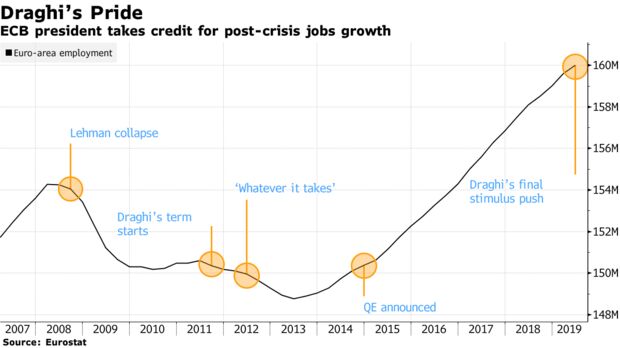

Three words — whatever it takes — defined Mario Draghi’s time as European Central Bank president, but he’s prouder of another number: 11 million jobs.

Hardly a public appearance goes by without Draghi mentioning employment growth in the euro zone as a justification for the extraordinary monetary stimulus he’s pushed through since 2011.

The focus on jobs might be understandable given that, despite all his efforts, he’s fallen far short on his primary mandate of inflation. That failure forced him into a last-ditch, and controversial, push in September to boost price growth. He leads his last Governing Council meeting on Thursday before retiring on Oct. 31.

So how has the region’s economy fared under Draghi, with his 2012 pledge to save the euro, and crisis-fighting measures such as negative interest rates and asset purchases? Here are some of the metrics that show his successes and failures.

Employment growth since 2013, when the 19-nation euro zone emerged from its double-dip recession, is unequivocally Draghi’s biggest economic achievement — if you discount that the single currency might not even exist today without his commitment the previous year to protect it when a debt crisis sparked breakup fears.

The labor market has underpinned the bloc’s recovery, feeding private spending and investment. It has become one of the biggest bulwarks against the recent chaos from the U.S.-China trade war, President Donald Trump’s protectionist rhetoric against Europe, and Brexit.

Looking deeper though, the picture is more complex. Germany has built on impressive job creation that started well before Draghi’s term, after domestic reforms, and was only briefly interrupted by the Great Recession. France can tell a similar tale, but labor markets in Spain and Greece along with some of the smaller euro members still haven’t made up the lost ground.

Regional differences are equally striking when analyzing economic growth. Aside from Greece and Cyprus — both deeply scarred after years of austerity and a near-collapse of their financial system — no country has done worse than Draghi’s native Italy in terms of total output per head.

The prime reason for the ECB’s record-low interest rates, cheap long-term loans and 2.6 trillion euros ($2.9 trillion) of asset purchases — so far — is its attempts to overcome weak inflation.

That hasn’t gone well. Consumer-price growth over Draghi’s eight-year term has averaged 1.2% which, unlike with his predecessors, falls short of the goal of “below, but close to, 2%.” It was even negative at times — so Draghi can at least console himself with the fact that he beat deflation.

Subdued price pressures are a mystery, and not only for Draghi. Central bankers around the world have puzzled over why low unemployment and rising wages aren’t translating into stronger inflation as standard economic models predict. The suspicion is that developments such as global supply chains and internet commerce are at least partially to blame.

The result is dwindling inflation expectations, a dangerous development for a central bank whose credibility hinges on convincing investors and the public that it can deliver on its mandate. The drift has kicked off a debate about whether incoming president Christine Lagarde needs to commission a review looking at both how the ECB sets policy and whether its definition of price stability, last updated in 2003, is still appropriate.

One other key indicator the ECB uses to gauge its success is lending by banks to companies and households, and that has responded better to stimulus. At just under 4%, credit is expanding at three times the rate of gross domestic product. Banks say that growth is threatened by negative interest rates, which squeeze their profit margins and might eventually force them to pull back.

One small economy has taken an outsized chunk of Draghi’s attention. Concerns about Greece’s public finances first surfaced in late 2009, and by 2015 the ECB was enmeshed in a banking crisis and game of political brinkmanship that threatened to splinter the single currency area.

Draghi’s kept the country’s lenders alive, by approving emergency liquidity, just long enough to allow a political solution that kept Greece in the bloc. Since then, the economy has started to recover, though lags far behind its peers. Draghi himself said this year that the Greek people paid a high price.Euro’s Future

For all the furor over a possible “Grexit” and the flirtations of factions in France and Italy with the idea of a future outside the currency union, membership has actually continued to grow. Latvia joined in 2014, Lithuania one year later, and other countries in eastern Europe have expressed an interest in doing likewise.

At the end of Draghi’s term, a measure of the probability of a breakup of the bloc is near a record low. It might be his ultimate legacy.

For Sarah Hewin, an economist at Standard Chartered Bank in London, both Draghi’s role in keeping the euro region intact and his record of “huge” job creation won’t be easily forgotten.

Those were “two really huge achievements during his time,” she told Bloomberg Television on Tuesday. “I think those are the ones that he’ll be remembered for.”

STRASBOURG (Reuters) – The European Commission said France and Italy draft budgets for next year might breach of European Union fiscal rules and it asked for clarification by Wednesday in letters sent to the countries’ finance ministers.

The EU executive has also issued budget warnings to Finland over its spending, and to Spain, Portugal and Belgium, who have submitted incomplete budget plans because of recent elections.

The EU’s move on Italy is considered necessary, since Rome plans to spend more to boost growth. It is unlikely to lead to a repeat of last year’s standoff, when Brussels forced the Italian government to amend its budget to avoid sanctions.

The letter to Italy, dated Oct. 22 and signed by economic commissioners Valdis Dombrovskis and Pierre Moscovici, said a preliminary assessment of the 2020 draft budget showed that it fell short of EU fiscal recommendations to reduce spending.

“Italy’s plan does not comply with the debt reduction benchmark in 2020,” the letter said.

That was the same message Brussels sent Italy last year. The situation since then has changed: Italy now has an EU-friendly government, the EU is pushing for more spending to counter recession risks and the current commission is also about to end its five-year mandate.

Moscovici told reporters on Tuesday the situation was different from last year and the commission would not ask for changes to Italy’s budget, reiterating the soothing message he delivered last week in an interview with Reuters.

Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte said Rome would provide the necessary information to Brussels as part of an exchange that finance ministry sources said did not cause concerns.

Brussels wants Italian Finance Minister Roberto Gualtieri to explain why, according to his draft budget, the country’s structural balance, which excludes one-off revenues and expenditures, would worsen by 0.1% of gross domestic product instead of improving by 0.6% as requested by the EU.

The Commission is also asking why net primary expenditure, which strips out interest payments, is budgeted to grow by 1.9% of output next year, instead of falling as recommended by the EU.

At the same time, Brussels is looking into whether it could grant Italy leeway for “unusual events”, it said in the letter. If granted, as widely expected after Rome’s request, the flexibility could allow Italy to deviate from fiscal targets without breaching EU fiscal rules.

Brussels sent similar warnings to French Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire, saying under the existing draft budget that Paris would breach EU rules on public debts.

France foresees no structural improvement next year, contrary to EU requests for an improvement worth 0.6% of GDP.

Paris will provide the requested clarifications, Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire said, adding that he had made a political choice to cut taxes in a bid to address social issues in France and the slowdown of the global economy.

The Commission, which is in charge of assessing the budgets of euro zone countries, also sent warnings to Spain, Portugal and Belgium, whose caretaker governments were not in a position to submit complete budgets by the Oct. 15 deadline set by EU rules.

Spain and Belgium have not formed new governments following this year’s elections, with Spain going to the polls again in November. In Portugal, a new cabinet has not yet been sworn in after elections held this month.

Countries occasionally present incomplete budgets because of elections, but the commission warned that the current budgetary measures laid out by the three caretaker executives could fall short of EU fiscal rules.

A warning letter was also sent to Finland because of its growing public spending. Helsinki replied, saying the measures were temporary and necessary to boost employment and improve public finances in the long run.

Reporting by Francesco Guarascio, editing by Alexandra Hudson, Ed Osmond, Larry King

Sunrise Communications Group bowed to investor pressure yesterday and scrapped its 6.3bn Swiss franc ($6.39bn) acquisition of Liberty Global’s Swiss cable business UPC.

The number two Swiss telecommunications group had battled to save the deal in the face of opposition from its biggest shareholder, Germany’s Freenet, which holds 25% of its stock, and activist investors including Axxion and AOC.

“This is a missed opportunity to promote competition in the Swiss market,” said Sunrise chief executive Olaf Swantee, who had planned to bundle mobile, broadband, TV and fixed-line products to close the gap to market leader Swisscom.

Sunrise will now focus on going it alone, top managers said, stressing that its dividend was not at risk from transaction costs and a 50mn Swiss franc break fee it owes Liberty Global, a firm set up by US cable pioneer John Malone.

The company cancelled an extraordinary shareholder meeting (EGM) planned for today to approve a 2.8bn franc cash call needed to finance the UPC deal, avoiding an embarrassing defeat on the measure.

Freenet and other investors had opposed the rights issue even in its scaled-down form, saying the takeover was too expensive, improperly financed and strategically flawed.

Influential proxy adviser ISS helped doom the deal by recommending shareholders oppose it.

“We regret cancelling the EGM. We have spent a significant amount of time engaging with our shareholders and continue to believe in the compelling strategic and financial rationale of the acquisition,” Sunrise chairman Peter Kurer said.

Not even support from investment banks UBS, Deutsche Bank, Morgan Stanley, Credit Suisse and Goldman Sachs was able to help Sunrise get the deal across the finish line.

Although the share purchase agreement technically remains in force until late February, Sunrise made clear the deal was effectively dead.

“Management is now really focused on implementing the standalone strategy. We respect the decision of the shareholders,” Swantee told Reuters, adding he did not expect to resume negotiations with Liberty Global.

Asked about his future after championing a deal that went awry, Swantee said only: “Our priority is stabilising Sunrise.”

Kurer, who has said he would likely be voted out of office if the deal failed, was also under fire. “We expect that he will now draw the consequences and immediately resign as chairman,” activist AOC said.

Sunrise shares, which had fallen more than 10% this year, gained 2.7% by 1230 GMT. Freenet boss Christian Vilanek saw more room for them to rise. “If we all pull together the stock can rise significantly over the next 12 to 24 months,” he said, adding Freenet had no plans to divest its Sunrise stake.

Analysts said the collapse would ease pressure on prices in the Swiss market. “Swisscom receives a ‘get out of jail free’ card,” Berenberg analyst Usman Ghazi said.

The future of UPC remained in limbo.

Ghazi said he doubted UPC would join forces with Salt, the third big Swiss player, but an investment banker involved in the deal said this was clearly a possibility, if not in the immediate future.

Liberty Global, which is exiting several European markets, was unlikely to change course and become a buyer, analysts said.

UPC Swiss head Severina Pascu said her operation remained a successful company with a strong standalone strategy.

Google lured billions of consumers to its digital services by offering copious free cloud storage. That’s beginning to change.

The Alphabet Inc. unit has whittled down some free storage offers in recent months while prodding more users toward a new paid cloud subscription called Google One. That’s happening as the amount of data people stash online continues to soar.

When people hit those caps, they realize they have little choice but to start paying or risk losing access to emails, photos and personal documents. The cost isn’t excessive for most consumers, but at the scale Google operates, this could generate billions of dollars in extra revenue each year for the company. Google didn’t respond to an email seeking comment.

A big driver of the shift is Gmail. Google shook up the email business when Gmail launched in 2004 with much more free storage than rivals were providing at the time. It boosted the storage cap every couple of years, but in 2013 it stopped. People’s in-boxes kept filling up. And now that some of Google’s other free storage offers are shrinking, consumers are beginning to get nasty surprises.

“I was merrily using the account and one day I noticed I hadn’t received any email since the day before,” said Rod Adams, a nuclear energy analyst and retired naval officer. After using Gmail since 2006, he’d finally hit his 15-gigabyte cap and Google had cut him off. Switching from Gmail wasn’t an easy option because many of his social and business contacts reach him that way.

“I just said, ‘OK, been free for a long time, now I’m paying,’” Adams said.

Other Gmail users aren’t so happy about the changes. “I am unreasonably sad about using almost all of my free google storage. Felt infinite. Please don’t make me pay! I need U gmail googledocs!” one person tweeted in September.

One self-described tech enthusiast said he’s opened multiple Gmail accounts to avoid bumping up on Google’s storage limits.

Google has also ended or limited other promotions recently that gave people free cloud storage and helped them avoid Gmail crises. New buyers of Chromebook laptops used to get 100 GB at no charge for two years. In May 2019 that was cut to one year.

Google’s Pixel smartphone, originally launched in 2016, came with free, unlimited photo storage via the company’s Photos service. The latest Pixel 4 handset that came out in October still has free photo storage, but the images are compressed now, reducing the quality.

More than 11,500 people in a week signed an online petition to bring back the full, free Pixel photos deal. Evgeny Rezunenko, the petition organizer, called Google’s change a “hypocritical and cash-grabbing move.”

“Let us remind Google that part of the reason of people choosing Pixel phones over other manufacturers sporting a similar hefty price tag was indeed this service,” he wrote.

Smartphones dramatically increased the number of photos people take — one estimate put the total for 2017 at 1.2 trillion. Those images quickly fill up storage space on handsets, so tech companies, including Apple Inc., Amazon.com Inc. and Google, offered cloud storage as an alternative. Now as those online memories pile up, some of these companies are charging users to keep them.

Apple has been doing this for several years, building its iCloud storage service into a lucrative recurring revenue stream. When iPhone users get notifications that their devices are full and they should either delete photos and other files or pay more for cloud storage, people often choose the cloud option.

In May, Google unveiled Google One, a replacement for its Drive cloud storage service. There’s a free 15 GB tier — enough room for about 5,000 photos, depending on the resolution. Then it costs $1.99 a month for 100 GB and up from there. This includes several types of files previously stashed in Google Drive, plus Gmail emails and photos and videos. The company ended its Chromebook two-year 100-GB free storage offer around the same time, while the Pixel free photo storage deal ended in October with the release of the Pixel 4.

Gmail, Drive and Google Photos have more than 1 billion users each. As the company whittles away free storage offers and prompts more people to pay, that creates a potentially huge new revenue stream for the company. If 10% of Gmail users sign up for the new $1.99-a-month Google One subscription, that would generate almost $2.4 billion in annual recurring sales for the company.

Adams, the Gmail user, is one of the people contributing to this growing Google business. The monthly $1.99 is a relatively small price to pay to avoid losing his main point of digital contact with the world.

“It’s worked this long,” Adams said. “I didn’t want to bother changing the address.”

De Vynck writes for Bloomberg.

Qatar is expected to be a $225bn economy by 2020, thus offering immense investment potential to foreign investors, as Doha eyes substantial inflow of foreign direct investment (FDI). The future of Qatar’s economy, as well as the FDI potential, was highlighted by senior officials from the Qatar Financial Center (QFC), Qatar Free Zones Authority (QFZA) and the Investment Promotion Agency of Qatar (IPAQ) at a recent event in New York.

“Qatar has invested significantly in its economy, generating gross domestic product growth that is expected to hit an impressive $225bn by 2020. This growth unlocked many investment opportunities in the country, and has already attracted the attention of foreign investors interested in establishing themselves in the Middle East,” said IPAQ chief executive Sheikh Ali al-Waleed al-Thani. Saud bin Abdullah al-Attiyah, deputy undersecretary for Economic Affairs, Ministry of Finance, said Qatar remains one of the world’s fastest-growing economies, with an abundance of investment opportunities across numerous sectors.

“This reflects the forward-thinking and progressive fiscal policies and legislative reforms introduced by Qatar that have already seen a positive impact, as noted by international ratings agencies including Moody’s and Standard and Poor’s, all of which underlines the nation’s attractiveness as an investment hub,” he added. Highlighting that Qatar’s regulatory, digital, entrepreneurial, and legislative frameworks off er a sustainable climate for global investors to prosper, Abdulla al-Misnad, deputy chief executive, QFZA, said the country’s free zones are committed to foster economic growth by focusing on sectors where Qatar has a “strong value proposition”.

“We aim to attract companies with willingness to play an active role in our vision towards a dynamic and diversified economy, and have the ability to penetrate large, fast-growing underserved global markets,” he said. Sarah al-Dorani, chief marketing officer, QFCA showcased Qatar as the ideal location (for global companies) to expand in the region. The event saw a range of experts discuss the outlook for foreign investors in Qatar; some of Qatar’s rapidly growing sectors including FDI in financial technology, as well as the upward investing trends seen in the past several years.

The event was hosted by Jason Kelly, New York Bureau Chief of Bloomberg and included a lineup of highly promi- nent speakers including ambassador Anne Patterson, President of the US- Qatar Business Council; Rachel Duan, president and chief executive of GE’s Global Growth Organisation; and James Zhan, Director of Investment and Enterprise at the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.