(Bloomberg) — Drive down any highway in the world and you’ll see countless reminders that the price of Big Oil’s primary product is rising. What’s less obvious is how the inflationary pressures from transport fuel are being amplified by another part of this sprawling industry — chemicals.

The cost of the building blocks for everything from plastics to paint has surged over the past year. That’s great for companies like Exxon Mobil Corp. and Royal Dutch Shell Plc, whose petrochemical units just earned their biggest profit in years.

But it’s unwelcome news for consumers as commodities from copper to lumber are already testing record highs. The price of materials like PVC and ethylene, staples of construction and manufacturing, have risen to the highest in at least seven years on a combination of pandemic-driven demand, the broader post-Covid recovery and once-in-a generation supply disruptions.

“The demand is coming from food, packaging, medical goods, protective equipment,” said Oswald Clint, senior research analysts at Sanford C Bernstein Ltd. “Does it add to inflation? Yes.”

Oil has advanced steadily this year, coming within a whisker of $70 a barrel in London this week. Yet even as higher crude prices boosted earnings from the oil majors’ exploration and production units, the performance of their petrochemical businesses really stood out.

In the first three months of this year, Exxon made $1.4 billion from chemicals, more than in any quarter since at least 2014, when oil prices were above $100 a barrel. More than a fifth of Shell’s $3.23 billion of adjusted net income for the period came from the division, the highest in four years.

Global Winners

It’s not just the oil majors seeing sales surge. Chemicals was the fastest growing unit at Indian conglomerate Reliance Industries Ltd. in the first three months of 2021, compared with the prior quarter.

Other winners from the boom include Brazil’s Braskem SA, Indorama Ventures PCL from Thailand, Celanese Corp., Dow Inc. and LyondellBasell Industries NV in the U.S., and Saudi Basic Industries Corp., according to Jason Miner, Bloomberg Intelligence chemicals analyst.

“It’s a story of the strength of the intermediates,” Shell chief financial officer Jessica Uhl told investors on April 29, referring to compounds that are derived from basic petrochemical feedstocks. Demand is growing as the economy recovers, notably in Asia, she said.

For example, the price of styrene monomer — used in medical devices and latex — surpassed $1,000 a ton in the first quarter, Uhl said. The average price of the chemical at the port of Rotterdam in the Netherlands was about $700 a ton in 2020, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

The global vaccination drive and large stimulus packages are boosting consumer sentiment and demand from health care, packaging, consumer durables, textiles and automobiles, Reliance said in its earnings presentation last week. Demand for polymers and polyesters has been particularly strong in India, it said.

Trouble in Texas

This isn’t just a story about strong demand. The chemicals industry is also just coming back from several major supply disruptions.

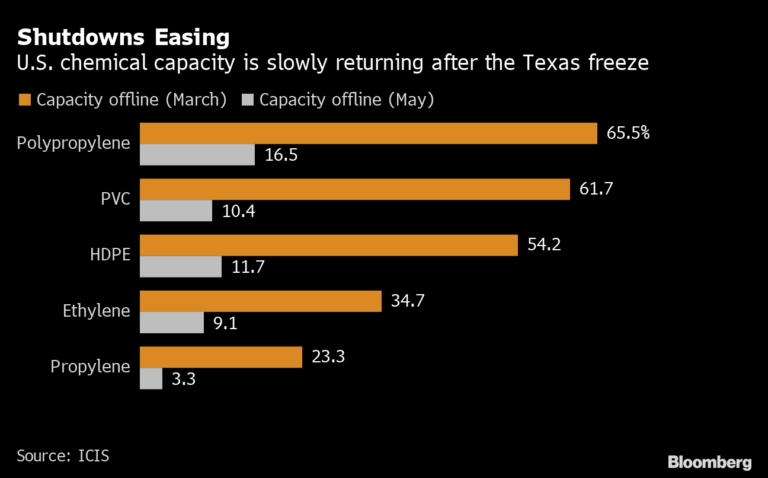

Back-to-back hurricanes on the U.S. Gulf Coast last year were followed by unusually cold weather in February, which knocked out much of the electricity grid in Texas and forced giant petrochemical facilities to shut down. Two months later, many are still not back working at full-capacity.

The region has become a dominant player in the world’s plastics trade thanks to natural gas liquids — a cheap petrochemical feedstock — coming out of the Texas shale boom. For example, North America is the world’s biggest producer of high-density polyethylene, used in everything from shampoo bottles to snowboards. It’s also the largest exporter of PVC.

“The big freeze sent a shockwave through global petrochemical markets,” Vienna-based consultant JBC Energy GmbH said in a note. While almost all of the plants that were disabled by the weather have been brought back online, inventories of many chemicals are still low, keeping prices elevated, it said.

The price of ethylene, the chemical building block for everything from plastics to solvents, reached a seven-year high of 59.5 cents a pound in March, according to ICIS, a data and analytics provider. PVC reached a record high of $1,625 a ton that month.

Even recycled plastic is in high demand, with the price of polyethylene terephthalate, or PET, used for drinks bottles and packaged food, reaching a 10-year high of 1,250 euros ($1,519) a metric ton in northwest Europe on Wednesday, according to S&P Global Platts. The price remained at that level Friday.

“If you were able to get back up and running quickly after the storm” you found a marketplace desperate for your product that “would almost pay any price to get it,” said Jeremy Pafford, head of North America at ICIS.

The tight supply and demand balance for many chemicals looks set to continue in the second quarter, Exxon Chief Executive Officer Darren Woods said on a call with analysts last week. Dow and LyondellBasell have said they are currently selling everything they produce and don’t anticipate being able to restock inventories until the third or fourth quarter.

To manufacture enough chemicals to satisfy customer demand and start building up its stockpiles again, the U.S. needs “four dull months” without any further disruption, said Pafford.

But hurricane season is just around the corner, and the global economy does not have time on its side.

The world is expected to see a surge in spending in the coming months as many countries end their lockdowns and cooped-up consumers dip into their savings or stimulus checks. That could happen alongside the continuation of pandemic-driven trends such as high demand for plastic medical goods as new strains of Covid-19 trigger fresh outbreaks around the world.

“Demand for personal protective equipment is unlikely to fade soon,” said Armaan Ashraf, an analyst at consultant FGE. “E-commerce, retail, durable goods demand is also likely to remain strong through the rest of this year as well.”

(Updates PET price in 17th paragraph)

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.