The long-feared war between Israel and Iran is now fully under way, and the repercussions threaten to include significant disruptions – not just for the two belligerents, but also for economies, peoples, and governments around the world.

To understand how and why an armed conflict between two regional powers could have such a widespread impact, start by considering the following:

1. Iran’s reserves of crude oil and natural gas are, respectively, the second- and third-largest in the world;

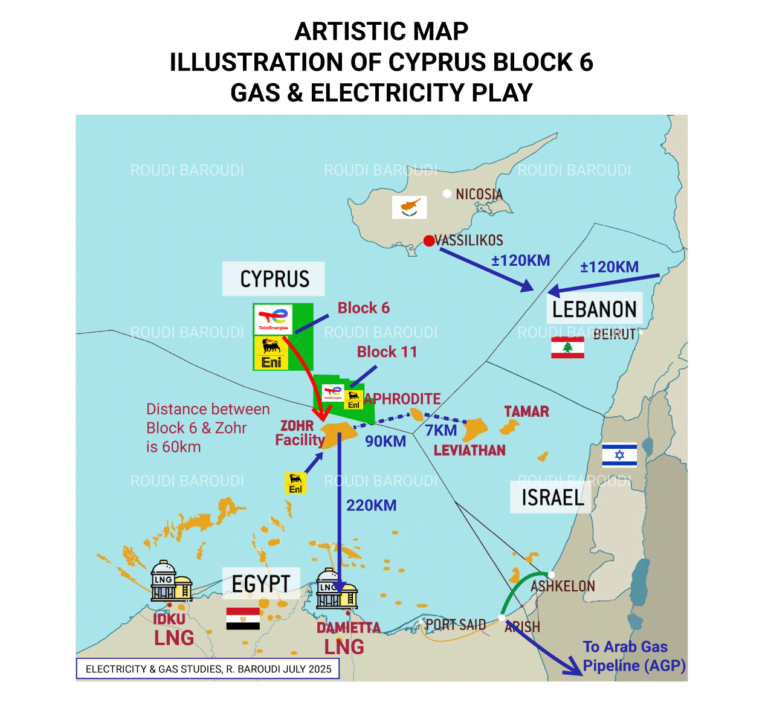

2. While Israel has posited Iran’s alleged nuclear activities as its reason for going to war, its strikes have also focused on Iran’s oil and gas infrastructure;

3. At the time of this writing, five of Iran’s nine major oil refineries had been hit and knocked out of service, along with storage depots and other facilities;

4. Israeli forces also started a huge fire at the South Pars gas field, which Iran shares with Qatar – and which holds almost as much gas as all of the other known gas fields on Earth.

5. For good measure, Iranian strikes against the Israeli refinery complex at Haifa have led to the shutdown of several offshore platforms, further crimping regional hydrocarbon output;

Now consider that it gets worse. The destruction or shutdown of Iran’s ability to extract, process, distribute, and export hydrocarbons would cause tremendous problems at home, and put upward pressure on prices everywhere, although the global impact would likely be manageable. The situation would be far more disruptive if Israeli attacks hit Bandar Abbas area. That could cause prices for gas – and other forms of energy – to soar on world markets.

And yet even this is not the greatest peril threatened by this war. That desultory honour goes to the possibility that traffic could be disrupted in the Strait of Hormuz, the relatively narrow channel that connects the Gulf to the open ocean. The passage is only 40 kilometres at its narrowest spot, wending for over 150 kilometres between Oman and the United Arab Emirates, to the west and south, and Iran’s Hormozgan Province to the east and north. Hormozgan is also home to the famous port city of Bandar Abbas, which hosts a giant oil and petrochemical complex that has already been struck at least once by Israeli forces.

What really matters for our purposes is that Hormuz also connects several other of the world’s most prolific oil and LNG producers – including Iraq, Kuwait, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia – to their overseas clients. As a result, every day, about a quarter of the world’s crude oil and LNG requirements exit the Gulf through Hormuz, making it the most strategically important chokepoint of our times. If this flow were halted or even significantly slowed, the consequences could be disastrous for much of the world. Although most of these exports are typically bound for markets in Asia, even a brief reduction in available oil and gas could send crude prices, currently a little more than $70 a barrel, shooting past $100 or even $120 in short order.

If such a supply crisis lasted any length of time, the global economy would enter uncharted territory. Not only would sky-high energy prices cause inflation to rise across the board, but fuel shortages could also be expected to cripple businesses of every size and sort. Transport and manufacturing, food processing and medical research, power generation, household heating and cooling, even the Internet itself: everything that depends on energy could slow to a trickle. A global recession would almost certainly ensue, and given the current trade environment, that might lead to another Great Depression.

So what might cause such an interruption? There are several possibilities, including the accidental sinking or crippling of a supertanker or two in just the right (i.e., wrong) place(s). Even if one or more accidents did not make Hormuz physically impassable, they could make insurance rates prohibitively expensive, causing many would-be off-loaders to decide against hazarding their ships amid the crossfire. Alternatively, Iran could decide to close the strait in order to punish the “international community” in general, for not doing enough to rein in the Israelis.

Whatever the rationale, the potential for global economic ruin – not to mention the ecological and public health risks posed by leaks of oil, nuclear materials, and/or other toxins into the environment – is simply not a risk that most intelligent people want to run. It therefore behooves those with the power to change the situation to do everything they can to end the conflict before its costs become more than a fragile world economy can bear.

Another is how to get Iran to behave itself, and that, too, shapes up as a difficult task. The Islamic Republic has spent most of the past half-century seeking to undermine US and Israeli influence over the region, and its substantial investments in proxy militias abroad and its own military at home may be skewing high-level decision-making. As the saying goes, when all you have is hammer, everything starts to look like a nail.

Despite these obstacles, it remains a fact that war is almost never preferable to negotiation. Iran and Israel agree on very little, their objectives are often in direct opposition to one another, and each views the other as a murderous and illegitimate state. Nonetheless, whether they realise it or not, both sides have a vested interest in ending the current conflict. Given the massive disparities in their respective strengths and weaknesses, this conflict could turn into a long-term bloodletting in which the value of anything achieved will be far outstripped by the cost in blood and treasure.

But who will get the two sides to so much as consider diplomacy when both of them are increasingly committed to confrontation? Although several world leaders have offered to act as mediators, the belligerents don’t trust very many of the same people. To my mind, this opens a door for Qatar, which has worked assiduously to maintain relations with all parties – and which already has a highly impressive record as a peacemaker – to step up in some capacity.

Whether it provides a venue for direct talks, a diplomatic backchannel for exchanging messages, or some other method, Doha has proved before that it can be a stable platform and a powerful advocate for peaceful negotiations. Let us hope it can do so again.

- Roudi Baroudi is a four-decade veteran of the oil and gas industry who currently serves as CEO of Energy and Environment Holding, an independent consultancy based in Doha.