Ρούντι Μπαρούντι: Να Τερματιστεί η Σύγκρουση Ισραήλ- Ιράν, πριν το Κόστος της Γίνει μη Διαχειρίσμο

Σήμα κινδύνου για τις επιπτώσεις που θα έχει ο πόλεμος μεταξύ Ισραήλ και Ιράν, σε όλο τον κόσμο στέλνει ο ειδικός αναλυτής στα ενεργειακά Ρούντι Μπαρούντι. Σε συνομιλία που είχαμε μαζί του με αφορμή άρθρο του που δημοσιεύτηκε στους Gulf Times. O κ. Mπαρούντι εστιάζει στις ενεργειακές επιπτώσεις σημειώνοντας ότι «τα αποθέματα αργού πετρελαίου και φυσικού αερίου του Ιράν

είναι, αντίστοιχα, τα δεύτερα και τρίτα μεγαλύτερα στον κόσμο. Ενώ το Ισραήλ έχει εξηγήσει ότι οι υποτιθέμενες πυρηνικές δραστηριότητες του Ιράν ως τον λόγο.

για τον οποίο ξεκίνησε τον πόλεμο, οι επιθέσεις του έχουν επικεντρωθεί επίσης στις υποδομές πετρελαίου και φυσικού αερίου του Ιράν. Πέντε από τα εννέα μεγάλα διυλιστήρια πετρελαίου του Ιράν είχαν πληγεί και τεθεί εκτός λειτουργίας, μαζί με αποθήκες και άλλες εγκαταστάσεις, ενώ οι ισραηλινές δυνάμεις προκάλεσαν επίσης μια τεράστια πυρκαγιά στο κοίτασμα φυσικού αερίου South Pars, το οποίο το Ιράν μοιράζεται με το Κατάρ – και το οποίο περιέχει σχεδόν τόσο φυσικό αέριο όσο όλα τα άλλα γνωστά πεδία φυσικού αερίου στη Γη. Επίσης οι ιρανικές επιθέσεις εναντίον του ισραηλινού συγκροτήματος διυλιστηρίων στη Χάιφα οδήγησαν στο κλείσιμο αρκετών υπεράκτιων πλατφορμών, μειώνοντας περαιτέρω την περιφερειακή παραγωγή υδρογονανθράκων».

Ο κ.Μπαρούντι εκτιμά ότι η κατάσταση μπορεί να επιδεινωθεί. «Η καταστροφή ή η διακοπή της ικανότητας του Ιράν να εξάγει, να επεξεργάζεται, να διανέμει και να εξάγει υδρογονάνθρακες θα προκαλούσε τεράστια προβλήματα στο εσωτερικό και θα ασκούσε ανοδική πίεση στις τιμές παντού, αν και ο παγκόσμιος αντίκτυπος θα ήταν πιθανότατα διαχειρίσιμος. Η κατάσταση θα ήταν πολύ πιο ανησυχητική εάν οι ισραηλινές επιθέσεις έπλητταν την περιοχή Μπαντάρ Αμπάς. Αυτό θα μπορούσε να προκαλέσει την εκτόξευση των τιμών του φυσικού αερίου – και άλλων μορφών ενέργειας – στις παγκόσμιες αγορές», τονίζει.

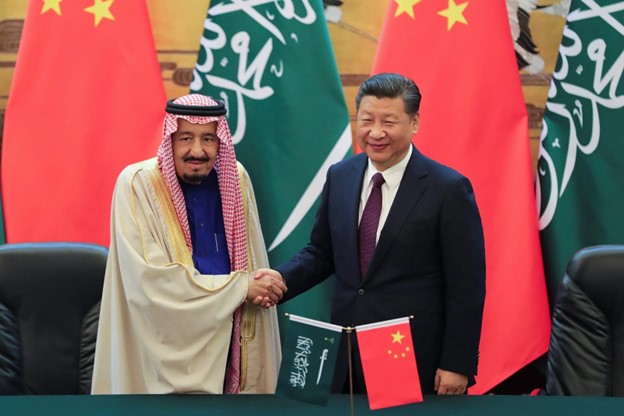

Δίνει μάλιστα μεγάλη έμφαση στα στενά του Ορμούζ καθώς συνδέει αρκετούς άλλους από τους πιο παραγωγικούς παραγωγούς πετρελαίου και LNG στον κόσμο – συμπεριλαμβανομένων του Ιράκ, του Κουβέιτ, του Κατάρ και της Σαουδικής Αραβίας – με τους πελάτες τους στο εξωτερικό.

«Ως αποτέλεσμα, κάθε μέρα, περίπου το ένα τέταρτο των παγκόσμιων αναγκών σε αργό πετρέλαιο και LNG εξέρχεται από τον Κόλπο μέσω του Ορμούζ, καθιστώντας τον το πιο στρατηγικά σημαντικό σημείο συμφόρησης της εποχής μας. Εάν αυτή η ροή σταματήσει ή ακόμη και επιβραδυνθεί σημαντικά, οι συνέπειες θα μπορούσαν να είναι καταστροφικές για μεγάλο μέρος του κόσμου. Αν και οι περισσότερες από αυτές τις εξαγωγές συνήθως προορίζονται για τις αγορές της Ασίας, ακόμη και μια σύντομη μείωση του διαθέσιμου πετρελαίου και φυσικού αερίου θα μπορούσε να εκτινάξει τις τιμές του αργού πετρελαίου, που επί του παρόντος είναι λίγο πάνω από 70 δολάρια το βαρέλι, πάνω από τα 100 ή ακόμα και τα 120 δολάρια σύντομα. Αν μια τέτοια κρίση εφοδιασμού διαρκούσε για κάποιο χρονικό διάστημα, η παγκόσμια οικονομία θα εισερχόταν σε αχαρτογράφητα εδάφη. Όχι μόνο οι υπερβολικά υψηλές τιμές ενέργειας θα προκαλούσαν αύξηση του πληθωρισμού σε όλους τους τομείς, αλλά οι ελλείψεις καυσίμων θα μπορούσαν επίσης να παραλύσουν επιχειρήσεις κάθε μεγέθους και είδους. Μεταφορές και μεταποίηση, επεξεργασία τροφίμων και ιατρική έρευνα, παραγωγή ενέργειας, θέρμανση και ψύξη οικιακών συσκευών, ακόμη και το ίδιο το Διαδίκτυο: όλα όσα εξαρτώνται από την ενέργεια θα μπορούσαν να επιβραδυνθούν σε μικρό βαθμό. Μια παγκόσμια ύφεση σχεδόν σίγουρα θα ακολουθούσε, και δεδομένου του τρέχοντος εμπορικού περιβάλλοντος, αυτό θα μπορούσε να οδηγήσει σε μια ακόμη Μεγάλη Ύφεση».

Ο κ. Μπαρούντι καταλήγει ότι η πιθανότητα παγκόσμιας οικονομικής καταστροφής – για να μην αναφέρουμε τους οικολογικούς κινδύνους και τους κινδύνους για τη δημόσια υγεία που προκαλούν οι διαρροές πετρελαίου, πυρηνικών υλικών ή και άλλων τοξινών στο περιβάλλον – απλά δεν είναι ένας κίνδυνος που οι περισσότεροι έξυπνοι άνθρωποι θέλουν να βιώσουν. «Επομένως, αρμόζει σε όσους έχουν τη δύναμη να αλλάξουν την κατάσταση να κάνουν ό,τι μπορούν για να τερματίσουν τη σύγκρουση προτού το κόστος της γίνει μεγαλύτερο από όσο μπορεί να αντέξει μια εύθραυστη παγκόσμια οικονομία»

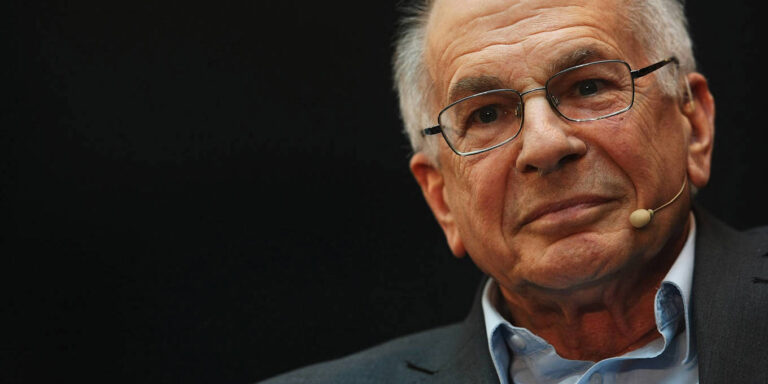

CAMBRIDGE – The recent passing of psychologist and Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman is an apt moment to reflect on his invaluable contribution to the field of behavioral economics. While Alexander Pope’s famous assertion that “to err is human” dates back to 1711, it was the pioneering work of Kahneman and his late co-author and friend Amos Tversky in the 1970s and early 1980s that finally persuaded economists to recognize that people often make mistakes.

When I received a fellowship at Stanford University’s Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences (CASBS) four years ago, it was this fundamental breakthrough that motivated me to choose the office – or “study” (to use CASBS terminology) – that Kahneman occupied during his year at the Center in 1977-78. It seemed like the ideal setting to explore Kahneman’s three major economic contributions, which challenged economic theory’s apocryphal “rational actor” by introducing an element of psychological realism into the discipline.

Kahneman’s first major contribution was his and Tversky’s groundbreaking 1974 study on judgment and uncertainty, which introduced the idea that “biases” and “heuristics,” or rules of thumb, influence our decision-making. Instead of thoroughly analyzing each decision, they found, people tend to rely on mental shortcuts. For example, we may rely on stereotypes (known as the “representativeness heuristic”), be overly influenced by recent experiences (the “availability heuristic”), or use the first piece of information we receive as a reference point (the “anchor effect”).

Second, Kahneman and Tversky’s work on “prospect theory,” which they published in 1979, critiqued expected utility theory as a model of decision-making under risk. Drawing on the “certainty effect,” Kahneman and Tversky argued that humans are psychologically more affected by losses than gains. The perceived loss from misplacing a $20 note, for example, would outweigh the perceived gain from finding a $20 note on the sidewalk, leading to “loss aversion.”

This insight is also at the core of the “framing effect.” The theory, developed while Kahneman was a fellow at CASBS and Tversky was a visiting professor at Stanford, posits that the way information is presented – whether as a loss or a gain – significantly influences the decision-making process, even when what is framed as a loss or gain has the same value.

Lastly, there is Kahneman’s popular masterpiece, the bestselling Thinking, Fast and Slow. Published in 2011 and offering a lifetime’s worth of insights, the book introduced the general public to two stylized modes of human decision-making: the “quick,” instinctive, emotional mode that Kahneman called System 1, and the “slower,” deliberative, or logical mode, which he called System 2. Humans, he showed, are prone to abandoning logic in favor of emotional impulses.

Kahneman received the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2002, despite, as he jokingly remarked, having never taken a single economics course. Nevertheless, his scholarship laid the groundwork for an entirely new field of economic research – and it had all begun in Study 6.

In particular, Kahneman’s work had a profound impact on University of Chicago economist Richard Thaler, who went on to become a Nobel laureate himself. As an assistant professor, Thaler managed to “finagle” a visiting appointment at the National Bureau of Economic Research, whose offices were located down the hill from CASBS, enabling him to connect with Kahneman and Tversky.

In 1998, Thaler co-authored a seminal paper with Cass Sunstein and Christine Jolls, introducing the concept of “bounds” on reason, willpower, and self-interest, and highlighting human limitations that rational-actor models had overlooked. By the time he received the Nobel Prize in 2017, Thaler had systematically documented “anomalies” in human behavior that conventional economics struggled to explain and conducted highly influential research (with Sunstein) on “choice architectures,” popularizing the idea that subtle design changes (“nudges”) can influence human behavior.

But as I gazed at the sweeping views of Palo Alto and the San Francisco Peninsula from the office window at CASBS, the birthplace of behavioral economics, I could not help but wonder whether Kahneman, despite his famously gentle nature, had perhaps been too critical of human decision-making. Are all deviations from “pure” economic logic necessarily “irrational”? Is our inability to align with the idealized model of economic analysis, coupled with our inevitable – albeit predictable – irrationality, really an inherent weakness? And is our tendency to rely on emotions rather than reason a fatal flaw, and if so, could our susceptibility to instinct ultimately lead to our downfall?

I wish I could ask Kahneman these questions. During my time there in 2020-21, Kahneman, affectionately known as “Danny” to all, was not just what CASBS called a “ghost” of the “study” – a former occupant who had been a major influence on my work – but also, happily, a vibrant, living legend who had enthusiastically invited me to discuss these very issues in person. Looking back, I regret my “planning fallacy” in not taking him up on his offer to deepen our conversation sooner – a sentiment shared by both my System 1 and System 2 modes. If “to err is human,” Danny taught me a poignant final lesson in human error.