LEBTALKS INTERVIEW: INTERNATIONAL ENERGY EXPERT ROUDI BAROUDI APPLAUDS ‘HISTORIC’ LEBANON-CYPRUS DEAL, DISMISSES ‘BASELESS’ CRITICISMS FROM NEIGHBORS

Following criticism of the Lebanon-Cyprus Maritime Boundary Agreement (MBA) by the governments of Israel and Turkiye, LebTalks spoke with energy and policy expert Roudi Baroudi, who has authored several books and studies on sea borders in the Eastern Mediterranean. Baroudi praised the pact as “full of positives” for the interests of both parties and stressed the words of Lebanese President Joseph Aoun, who pledged after signing the MBA that “this agreement targets no one and excludes no one.”

LebTalks: How significant is the signing of the maritime boundary agreement between Lebanon and Cyprus?

RB: The official signing of the Lebanon-Cyprus deal is a major achievement, one that confers important advantages on both parties. This process was delayed for a very long time for no good reason, so President Joseph Aoun and the government deserve congratulations for having seized the initiative, and for having seen the job through to completion. So do Cypriot President Nikos Christodoulides and his team, because they did the same thing. What made this historic agreement possible – after an impasse lasting almost two decades – was that Lebanon finally had a president who both understood the need for an MBA and made achieving it a top priority.

LebTalks: What does Lebanon gain by signing this deal?

RB: The agreement, which was reached by the negotiating teams in September, provides several benefits for both countries in the short, medium, and long terms.

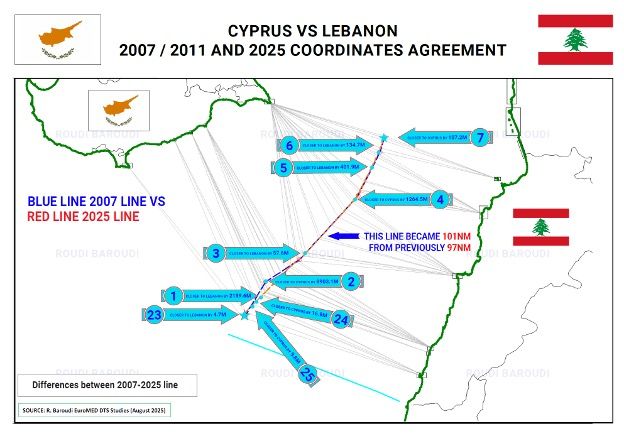

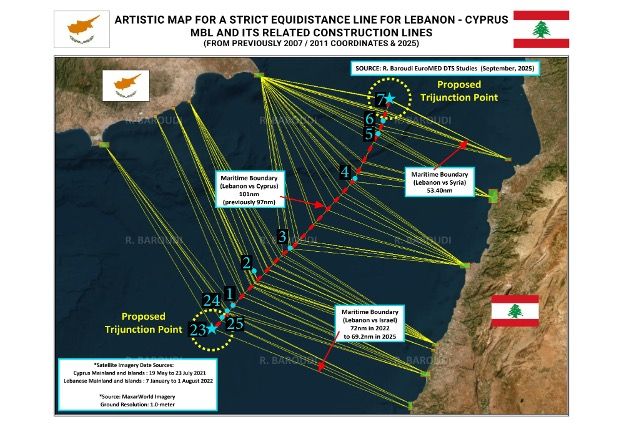

The new equidistance line between the two states, defined according to the rules and guidelines of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), provides a fair and largely uniform boundary between the two brotherly countries’ maritime zones. Most of the new turning points used to draw the line have moved in Lebanon’s favor compared to the earlier negotiation in 2011, giving it an extra 10,200 meters on its western front while Cyprus received 2,760 meters.

Crucially, the MBA wipes away all overlapping claims caused by previous uncertainty over the precise location of the border. Accordingly, this eliminates 108 km2 of (map attached) Lebanese offshore blocks that were actually in Cypriot waters, as well as 14 km2 of Cypriot blocks which were also on the wrong side of the line.

Apart from removing a key risk for would-be investors, the agreement also contributes to stability and security by providing clarity and thereby enabling easier cooperation, not just bilateral, but also, potentially, involving other states as well. It really is full of positives for both Lebanon and Cyprus, and therefore for the region as a whole.

LebTalks: What should Lebanon do to follow up on this agreement?

RB: To make the most of this clearer playing field, the logical next step is for Lebanon and Cyprus to immediately start drafting a joint development agreement, which would allow them to have a smooth partnership in place for any hydrocarbon reserves which are found to straddle their maritime boundary.

Perhaps the most important feature of the Lebanon-Cyprus MBA is that it provides a clear and stable starting point, putting Lebanon in ideal position to finish defining its maritime zones. The new line means that Lebanon’s existing maritime boundary arrangements with Israel, signed in 2022, should be tweaked a little, but it also makes it easier to do that – and to negotiate a similar agreement in the north with Syria when that country’s new leadership is ready to do so.

LebTalks: What about the objections voiced by Irael and Turkiye?

RB: With all due respect, these claims and complaints are completely baseless. As President Aoun has stressed from the very day it was signed, this accord targets no one, excludes no one, challenges no one else’s borders, and undermines no one else’s interests. I know there has been some negative commentary from both Israel and Turkiye, but there really is nothing here for anyone to be upset about. The line agreed to by Lebanon and Cyprus, which Turkiye has claimed is ‘unfair’ to residents of the self-styled ‘Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus’, is literally several kilometers away from any waters claimed by the TRNC. Beirut and Nicosia were very careful to make sure of this.

As for the Israelis, the only material change relating to the Lebanon-Cyprus line is that it pushes the Israel-Cyprus line in Cyprus’ favor. But that’s not Lebanon’s fault. Or Cyprus’ or anyone else’s. It’s just a fact of new mapping technologies, which today are far more precise and more accurate than those used when the Israel-Cyprus line was drawn in their 2011 treaty.

On that subject, I would also note for all stakeholders in the East Med that while Lebanon and Cyprus are the region’s only full-fledged members of UNCLOS, all states are subject to its rules and precedents, which have become part of Customary International Law. Since the Lebanon-Cyprus deal adheres strictly to those rules and the science behind them, the criticisms haven’t got a legal leg to stand on. This is especially true with regard to Israel, whose own treaty with Cyprus was negotiated on the basis of the very same laws, rules, and science.

I have to assume that a lot of this is posturing, that both Israel and Turkiye will settle down once they’ve had more time to analyze the deal and see that, far from damaging them in any way, it could help all concerned by contributing to regional stability and economic growth. And again, I would go back to Aoun’s words on signing day, when he declared that “this agreement should be a foundation for wider regional cooperation, replacing the language of violence, war, and ambitions of domination with stability and prosperity.”