IMF’s misstep on climate finance

The International Monetary Fund seems determined to dilute one of the best examples of global co-operation in response to the economic disruptions induced by the Covid-19 pandemic and climate change. It must change course now, before it is too late.

The IMF’s allocation of $650bn in special drawing rights (SDRs, the Fund’s reserve asset) in August was long encouraged and widely welcomed. Given the IMF’s tight rules, it was clear from the start that the vast majority of SDRs would go to countries that did not need them. As a result, G7 leaders pledged to re-channel upwards of $100bn of their allocations to “countries most in need of … pandemic [support to] stabilise their economies, and mount a green and global recovery … aligned with shared development and climate goals.”

While these moves seem small compared to the $17tn that rich countries have spent to support their economies during the pandemic, they were nonetheless significant. In October, just two months after the allocation, the G20 backed a plan by the IMF and the World Bank to develop and implement a Resilience and Sustainability Trust, which would allow wealthy countries to channel their allotments to low- and middle-income countries vulnerable to economic shocks. Because the RST could be used to address risks related to climate change, it would fill a glaring gap in international finance. The IMF announced that it would have a proposal ready for its 2022 spring meetings.

But will it be enough?

Extreme weather events like floods and hurricanes can trigger financial instability in vulnerable countries as they wipe out capital stock and sources of foreign exchange. Likewise, countries dependent on fossil-fuel exports face fiscal uncertainty as demand for oil and gas decreases to meet climate goals. In both cases, spillover effects can negatively affect trade. Countries confronting such conditions must undertake a structural transformation of their economies. But many low- and middle-income countries lack access to the cost-effective, flexible financing they need.

A well-designed RST would make the IMF criteria for resource allocation and country eligibility more adaptable. Unfortunately, five design flaws in the IMF’s approach would render the planned RST ineffective for most climate-vulnerable countries.

The first flaw concerns eligibility. IMF programmes discriminate on the basis of income, but climate change does not. While the G20 explicitly called for the establishment of an RST covering low-income and climate-vulnerable middle-income countries, the IMF has adopted a narrow interpretation according to which middle-income countries would be eligible only if they do not exceed a certain income threshold.

But traditional measures of income are a poor criterion for determining eligibility. The IMF must adjust its thinking to actual circumstances and ensure that eligibility is based on climate vulnerability. It should not be controversial to integrate into the criteria simple measures such as susceptibility to physical climate risks like floods, droughts, and hurricanes, or economic factors like the share of fossil-fuel exports in total foreign-exchange earnings.

Second, there is a problem with the terms and accessibility of the funds. Developing countries lack the fiscal space to mobilise domestic resources to address the structural changes their economies need. Many also lack access to external resources on reasonable borrowing terms. But the IMF is proposing that RST users be charged the SDR interest rate (currently five basis points and on the rise) plus a margin of up to 100 basis points. These rates are not very different from what the Fund currently charges middle-income countries. More problematic is the access limits, which would be 100% of quota, or less than the SDR equivalent of $1bn. These guidelines would do little to address the financing needs of all but the smallest countries.

The third flaw is the IMF’s insistence on conditionality. The Fund sees the RST as a top-up scheme for existing programmes. This is deeply troubling. According to the IMF’s own research, its existing lending facilities are stigmatised, owing to their high levels of conditionality and low levels of performance with respect to economic recovery and other social outcomes. The RST was supposed to be a new instrument that recognises and channels resources to the countries that are most vulnerable to climate change. But what the IMF plans is repackaged business as usual.

Climate-vulnerable countries have not applied for IMF support even during the pandemic, when the Fund has experienced the largest use of its facilities. Adding a small top-up at the same price and level of conditionality essentially will lock up much-needed financing for climate resilience.

The fourth flaw is that even though the IMF is only now devising a climate-change strategy, it would head the RST. Multilateral and regional development banks are also prescribed SDR institutions, and they have a longer view and a stronger track record on climate policy. They need to be part of the RST’s governance.

Lastly, there is the question of scale. IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva has said the RST would be funded with around $30bn initially and then scaled up to $50bn. While the RST alone cannot be expected to substitute finance needed to address the intensifying effects of climate change, the needs assessment released by the Standing Committee on Finance of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change put the figure at $6tn, and other estimates are significantly higher. At the recent UN Climate Change Conference (COP26), Barbados Prime Minister Mia Amor Mottley, whose country is among the world’s most vulnerable, proposed an annual increase in SDRs of $500bn for 20 years to finance resilience and sustainability.

The IMF’s shareholders and stakeholders must reconsider the RST’s design. To succeed, it must include all climate-vulnerable developing countries, regardless of income level. It must provide low-cost financing that does not undermine members’ debt sustainability and is not linked to pre-existing IMF programmes with onerous conditionalities. It must be governed by key stakeholders in development-finance institutions. And it must scale appropriately over time.

The IMF must make the necessary adjustments to its proposal for the RST. If it cannot, creditor countries should refrain from capitalising it. — Project Syndicate

• The authors are members of the Task Force on Climate, Development and the International Monetary Fund.

NEW YORK – One way or another, central banks’ behavior will have to change with the climate. But it should evolve only because climate change will create new constraints and drive new forms of public and private economic activity. Central banks’ primary function should not change, nor should they adopt “green” targets that could undermine the pursuit of their traditional objectives: financial stability and price stability (which in the United States is a dual mandate of price stability and maximum employment).

Climate change will be a defining global issue for decades to come, because we are still a very long way from ushering in a low-carbon, climate-resilient world. Three features of our greenhouse-gas (GHG) emissions will impede the appropriate response. First, the benefits (cheap energy) are enjoyed in the present while the costs (global warming) are incurred in the future. Second, the benefits are “local” (they accrue to the GHG emitter) while the costs are global – a classic externality. Third, the most efficient methods of limiting GHG emissions impose disproportionate burdens on developing countries, while the task of compensating poor countries remains politically fraught.

The most efficient way to address climate-change externalities is through targeted fiscal and regulatory measures. Pigouvian taxes or tradable quotas would create the right incentives for reducing GHG emissions. Carbon taxes, as advocated by William D. Nordhaus of Yale University, must become the global norm (though it is difficult to envisage a global carbon tax working without a significant transfer of wealth from developed to developing countries). Rules and regulations targeting energy use and emissions can complement green taxes and quotas, and public spending can support research and development in the green technologies that we will need.

What does not belong in the mix is a green mandate for central banks. To be sure, legal mandates can change, and central banks have a well-established tradition of exceeding them. The European Central Bank’s financial-stability mandate is secondary to – “without prejudice to” – its price-stability mandate. This did not prevent it from acting decisively and quite effectively during the global financial crisis, the eurozone sovereign debt crisis, and the COVID-19 crisis, even when this meant overriding the price-stability target in 2021 and likely also in 2022. Moreover, Article Three of the Treaty on European Union explicitly provides for “a high level of protection and improvement of the quality of the environment,” so it is easy to see how the ECB’s financial-stability and monetary instruments could be used to target climate change.

But that does not mean they should be used in this fashion. The standard monetary-policy instruments (one or more policy interest rates, the size and composition of the central bank’s balance sheet, forward guidance, and yield curve control) are typically used to target price stability or the dual mandate. Judging by the results, there is no spare capacity in the monetary-policy arsenal.

These monetary-policy instruments impact financial stability as well, and not always in desirable ways. In addition, capital and liquidity requirements underpin micro- and macroprudential stability; and central banks can impose additional conditions on the size and composition of regulated entities’ balance sheets. As the lender and market maker of last resort, the central bank can choose its eligible counterparties, the instruments accepted as collateral or bought outright, and the terms and conditions on which it lends or makes outright purchases.

There is no doubt that climate change affects a central bank’s price-stability objective, including through current and anticipated changes in aggregate demand and supply, energy prices, and other channels. Climate change also could significantly alter the transmission of monetary policy, and thus will have to become an integral part of the models that guide central banks in pursuit of their primary objectives.

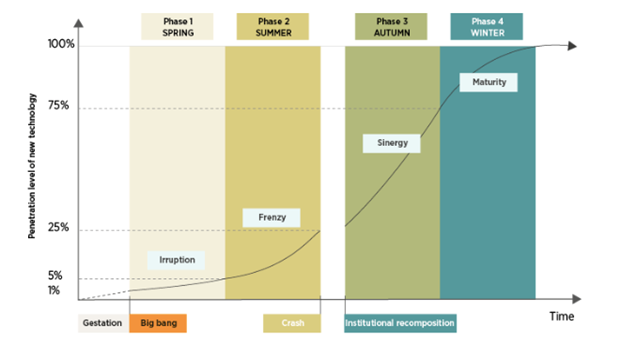

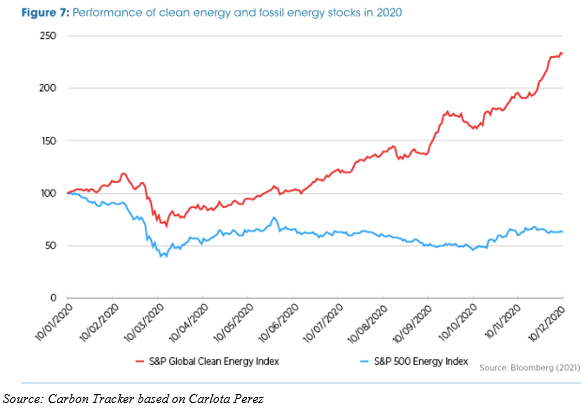

Green issues also affect financial stability in major ways. Extreme weather events can damage assets held by financial institutions and their counterparties. Climate-mitigation and adaptation efforts can depress the value of assets, potentially leaving many “stranded” or worthless. A central bank’s financial-stability mandate requires it to recognize and respond appropriately to the foreseeable effects that climate change will have on asset valuations and on the liquidity and solvency of all systemically important financial entities and their counterparties in the real economy.

But anticipating and responding appropriately to these risks now and in the future does not mean that higher capital or liquidity requirements should be imposed on “brown” loans, bonds, and other financial instruments. Financial-stability risks and global-warming risks are not perfectly correlated. Moreover, there are no redundant financial-stability policy instruments, and capital and liquidity requirements have a clear comparative advantage in pursuing financial-stability objectives, just as carbon taxes and emissions-trading systems have a clear comparative advantage in pursuing and achieving “green” objectives.

The shocks and disruptions caused by climate change will complicate central banks’ pursuit of their price-stability and financial-stability mandates. The last thing they need is to feel pressure to load additional objectives on their limited instruments. Just as it makes no sense to use carbon taxes or emissions-trading schemes to target financial stability, it makes no sense to use capital and liquidity requirements to address global warming. The appropriate tools to address climate change – fiscal and regulatory – are well-known and technically feasible. What is missing is the foresight, logic, and moral courage to deploy them.