Différends Maritimes en Méditerranée Orientale: Comment en Sortir

Les différends de frontières maritimes en Méditerranée orientale empêchent l’exploitation raisonnée des récentes découvertes énergétiques dans la région :

un nouveau livre montre comment résoudre pacifiquement les conflits frontaliers maritimes.

L’ouvrage se présente comme une feuille de route pour aider les pays côtiers à exploiter les ressources offshore

Un nouveau livre de l’expert en politique de l’énergie Roudi Baroudi met en lumière des mécanismes souvent négligés qui pourraient aider à désamorcer les tensions et débloquer des milliards de dollars en pétrole et en gaz.

“Maritime Disputes in the Eastern Mediterranean: the Way Forward” («Différends Maritimes en Méditerranée Orientale: Comment en Sortir») -distribué par Brookings Institution Press- décrit le vaste cadre juridique et diplomatique dont disposent les pays qui cherchent à résoudre les conflits de frontières maritimes. Dans ce livre, M. Baroudi passe en revue l’émergence et l’influence (croissante) de la Convention des Nations unies sur le droit de la mer (CNUDM), dont les règles et les normes sont devenues la base de pratiquement toutes les négociations et de tous les accords maritimes. Il explique également comment les progrès récents de la science et de la technologie, notamment dans le domaine de la cartographie de précision, ont accru l’impact des lignes directrices de la CNUDM en éliminant les conjectures de tout processus de règlement des différends fondé sur celles-ci.

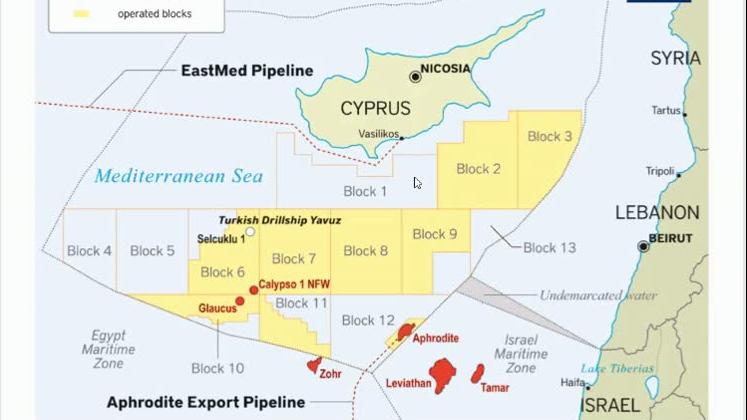

Comme le titre l’indique, l’ouvrage se concentre en grande partie sur la Méditerranée orientale, où les récentes découvertes de pétrole et de gaz ont souligné le fait que la plupart des frontières maritimes de la région restent discutées. L’incertitude qui en résulte ralentit non seulement l’utilisation des ressources en question (et le réinvestissement des recettes pour lutter contre la pauvreté et d’autres problèmes de société), mais augmente également le risque d’un ou plusieurs conflits meurtriers. M. Baroudi fait toutefois remarquer que, tout comme ces problèmes et leurs conséquences existent dans le monde entier, leur résolution juste et équitable dans une région pourrait contribuer à restaurer la croyance qu’ont les peuples et leurs dirigeants dans le multilatéralisme, et servir ainsi d’exemple.

Si les pays de la Méditerranée orientale acceptaient, en vertu des règles de la CNUDM, de régler leurs différends de manière juste et équitable, écrit-il, “cela donnerait une chance de démontrer que l’architecture de sécurité collective de l’après-guerre reste non seulement une approche viable mais aussi une approche vitale… Cela montrerait au monde entier qu’aucun obstacle n’est trop grand, aucune inimitié si ancrée et aucun souvenir si amer qu’il ne puisse-t-être surmonté en suivant les règles de base auxquelles tous les États membres des Nations unies ont souscrit en y adhérant: la responsabilité de régler les différends sans violence ou menace de violence”.

Le livre rappelle, de manière générale et spécifique, qu’il existe des leviers permettant d’uniformiser les règles du jeu diplomatique, une contribution utile à un moment où l’ensemble du concept de multilatéralisme est attaqué par certains des pays qui ont autrefois défendu sa création. L’ouvrage est écrit dans un style engageant, empruntant à plusieurs disciplines -de l’histoire et de la géographie au droit et à la cartographie- le rendant accessible et d’intérêt pour tous, des universitaires et des décideurs politiques aux ingénieurs et au grand public.

En attendant sa parution papier, ainsi que sa traduction en français prévue dans les prochaines semaines, le livre est disponible au format e-book. Dans le contexte actuel qui a forcé les maisons d’édition à adapter leur stratégie de lancement, l’ouvrage a fait l’objet ce jeudi d’un lancement organisé par TLN via zoom, avec la participation autour de l’auteur, de deux représentants éminents du Département d’État américain – Jonathan Moore (premier sous-secrétaire adjoint principal, Bureau des océans et des affaires environnementales et scientifiques internationales) et Kurt Donnelly (sous-secrétaire adjoint pour la diplomatie énergétique, Bureau des ressources énergétiques).

BONN – In the face of climate change, providing reliable supplies of renewable energy to all who need it has become one of the biggest development challenges of our time. Meeting the international community’s commitment to keep global warming below 1.5-2°C, relative to preindustrial levels, will require expanded use of bioenergy, carbon storage and capture, land-based mitigation strategies like reforestation, and other measures.

The problem is that these potential solutions tend to be discussed only at the margins of international policy circles, if at all. And yet experts estimate that the global carbon budget – the amount of additional carbon dioxide we can still emit without triggering potentially catastrophic climate change – will run out in a mere ten years. That means there is an urgent need to ramp up bioenergy and land-based mitigation options. We already have the science to do so, and the longer we delay, the greater the possibility that these methods will no longer be viable.

Renewable energy is the best option for averting the most destructive effects of climate change. For six of the last seven years, the global growth of renewable-energy capacity has outpaced that of non-renewables. But while solar and wind are blazing new trails, they still are not meeting global demand.

A decade ago, bioenergy was seen as the most likely candidate to close or at least reduce the supply gap. But its development has stalled for two major reasons. First, efforts to promote it had negative unintended consequences. The incentives used to scale it up led to the rapid conversion of invaluable virgin land. Tropical forests and other vital ecosystems were transformed into biofuel production zones, creating new threats of food insecurity, water scarcity, biodiversity loss, land degradation, and desertification.

In its Special Report on Climate Change and Land last August, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change showed that scale and context are the two most important factors to consider when assessing the costs and benefits of biofuel production. Large monocultural biofuel farms simply are not viable. But biofuel farms that are appropriately placed and fully integrated with other activities in the landscape can be sustained ecologically.

Equally important is the context in which biofuels are being produced – meaning the type of land being used, the variety of biofuel crops being grown, and the climate-management regimes that are in place. The costs associated with biofuel production are significantly reduced when it occurs on previously degraded land, or on land that has been freed up through improved agriculture or livestock management.

Under the 1.5°C warming scenario, an estimated 700 million hectares of land will be needed for bioenergy feedstocks. There are multiple ways to achieve this level of bioenergy production sustainably. For example, policies to reduce food waste could free up to 140 million additional hectares. And some portion of the two billion hectares of land that have been degraded in past decades could be restored.

The second reason that bioenergy stalled is that it, too, emits carbon. This challenge persists, because the process of carbon capture remains contentious. We simply do not know what long-term effects might follow from capturing carbon and compressing it into hard rock for storage underground. But academic researchers and the private sector are working on innovations to make the technology viable. Compressed carbon, for example, could be used as a building material, which would be a game changer if scaled up to industrial-level use.

Moreover, whereas traditional bioenergy feedstocks such as acacia, sugarcane, sweet sorghum, managed forests, and animal waste pose sustainability challenges, researchers at the University of Oxford are now experimenting with the more water-efficient succulent plants. Again, succulents could be a game changer, particularly for dryland populations who have a lot of arid degraded land suitable for cultivation. Many of these communities desperately need energy, but would struggle to maintain solar and wind facilities, owing to the constant threat posed by dust and sandstorms.

In Garalo commune, Mali, for example, small-scale farmers are using 600 hectares previously allocated to water-guzzling cotton crops to supply jatropha oil to a hybrid power plant. And in Sweden, the total share of biomass used as fuel – most of it sourced from managed forests – reached 47% in 2017, according to Statistics Sweden. Successful models such as these can show us the way forward.

Ultimately, a reliable supply of energy is just as important as an adequate supply of productive land. That will be especially true in the coming decades, when the global population is expected to exceed 9.7 billion people. And yet, if global warming is allowed to reach 3°C, the ensuing climatic effects would make almost all land-based mitigation options useless.

That means we must act now to prevent the loss of vital land resources. We need stronger governance mechanisms to keep food, energy, and environmental needs in balance. Failing to unleash the full potential of the land-based mitigation options that are currently at our disposal would be an unforgiveable failure, imposing severe consequences on people who have contributed the least to climate change.

Bioenergy and land-based mitigation are not silver bullets. But they will buy us some time. As such, they must be part of the broader response to climate change. The next decade may be our last chance to get the land working for everyone.