EMIR IN GREECE AND CYPRUS

Political 04.06.24

Interview by ALEXIA TASOULI

DIPLOMATIC CORRESPONDENT

POLITICAL.GR NEWSPAPER

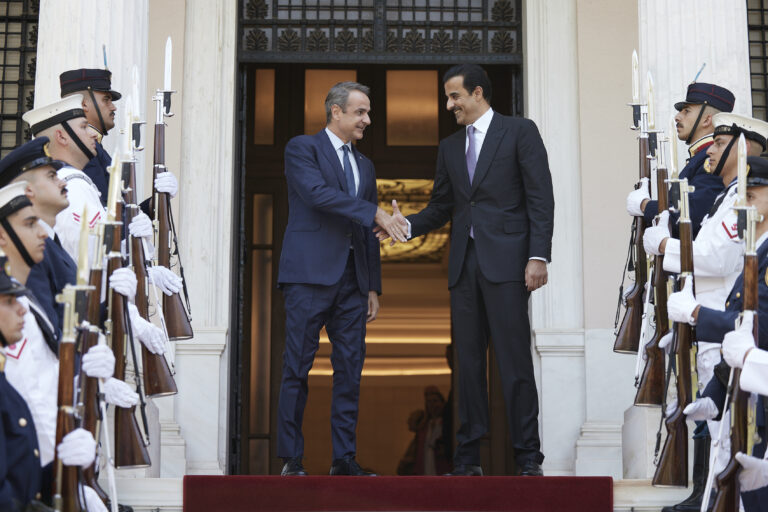

Athens, Friday 31st of May 2024: Qatar’s Emir Sheikh Tamim Bin Hamad AlThani paid official visits to Cyprus and Greece this week, meeting with senior officials from both countries as part of efforts to expand cooperation. International energy expert Roudi Baroudi, CEO of Dohabased independent consultancy Energy and Environment Holding, sat down to answer a few questions about the outcome and significance of the emir’s mission.

Question: Overall, how successful were HH the emir’s visits to Greece and Cyprus?

Answer: Both visits appear to have been very fruitful. HH the emir and his delegation held constructive talks with their counterparts in both countries, and all sides came away with clearer understandings of where the already strong relationships should go next, and how they can get there. Several important first steps were taken toward identifying likely areas for further cooperation, and now both sides have the information they need to come up with proposals for the next steps on several fronts.

Q: From your perspective, what are the main takeaways from HH the emir’s trip?

A: There are several elements at play here, multiple processes unfolding according to their own timelines, but all interrelated in some ways. The first thing to consider is that both visits constitute reaffirmations of Qatar’s traditional diplomatic strategy, much of which revolves around having stable and friendly relations with as many counterparts as possible. That might sound a little basic, but it’s really not: many governments “pick sides” in various international disputes, which often amounts to letting other countries decide your foreign policy for you. By contrast, the Qatari model seeks instead to be on good terms with all sides in most disputes, and the value of that approach has been on display for years: Doha has successfully used its good offices as a mediator in the past, and more recently it has done the same for ceasefire talks and other negotiations between Israel and Hamas.

This same philosophy also informs Qatar’s stances in the Mediterranean, where it looks for the warmest possible relations with Greece and Cyprus while simultaneously maintaining close ties with Türkiye, with which both Athens and Nicosia have been at odds for decades. I should mention, too, that Cyprus follows a similar path, maintaining friendly relations with both Israel and Lebanon, for example.

Both Cyprus and Greece also would like to play central roles in the development and buildout of facilities aimed at carrying energy to the European mainland. This is a core part of their respective plans to grow and develop their respective economies, and the necessary investment and expertise will require strong partnerships.

Q: So how do these priorities tie in with the emir’s visit?

A: In several ways, really. First, HH the emir’s goodwill visit is a reconnection: the COVID pandemic threw a lot of international issues into hibernation as governments everywhere spent a lot of time looking inward for several years. By visiting now, he’s demonstrating in general that he values Qatar’s relationships with both Cyprus and Greece. The reengagement also bodes well for particulars, and there are several opportunities for cooperation because the parties can help one another. Both Greece and Cyprus want to be part of plans to open new channels for natural gas into Europe, whether it’s Eastern Mediterranean gas or from further afield. For this they could find no better partner than Qatar, which, in addition to its own worldleading LNG industry, has also been acquiring stakes in energy assets around the world. But both countries also want investment in other sectors, too, and once again, both the Qatar Investment Authority, the country’s sovereign fund, and various private investors are on the hunt for moneymaking ventures.

Q: What does the emir’s trip mean for Greece, in particular?

A: To me the time looks ripe for more cooperation. The period since 20072008 has been very difficult, but the current government under Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis has done wonders, not just to stabilize the Greek economy and restore hope to the population, but also to help Greece regain its rightful place at the European table. The country is now looking to build on this foundation by fully embracing cuttingedge sectors like digital connectivity and cleantech, but also by reinvigorating its traditional shipping expertise by becoming a major logistics center and by getting more out if its hospitality sector, too. The long recession is over, and some asset classes look very attractive to Qatari investors – and others, as well – especially given the stronger, cleaner governance and leadership on which Mitsotakis has built his reputation.

Q: What about Cyprus?

A: Another European land of opportunity. All other things being equal, if the world operated according to logic instead of politics, Cyprus would already be a major energy hub. Its location makes it the ideal base for the Eastern Med’s burgeoning offshore gas industry, which also includes strategic ports, telecoms, and other support services. Many analysts see real potential in several sectors, including ports, banking, and a host of technologies. The increased economic activity will also introduce more people to the beaches and other attractions that make the island’s tourism industry so popular. Another ingredient is leadership: President Nikos Christodoulides has been in office for less than a year, but the former diplomat and foreign minister has already shown himself to be both a highly competent Head of State and a stern defender of his country’s economic development & interests.

And all this is not to mention the shipping of the gas itself, for Cyprus is not just part of the European Union: it is also very much an East Mediterranean country, so it stands to reason that it should become a gateway through which some of the world’s newest gas producers can sell their wares into the world’s largest gas market. Whether it’s a pipeline to Greece, an LNG plant to supply customers in Asia and East Africa, or both, it’s a nobrainer that Cyprus is the place to start the journey. To me, this is Cyprus’ destiny, and if it’s further Qatari investment that makes it happen, so much the better. Remember, too, that QatarEnergy is already involved in Cyprus’ gas industry, partnering with ExxonMobil to explore two offshore blocks. The Qataris know the LNG business like no one else, and their robust & steady reliability as partners is unchallenged: in 20172021, despite an illegal blockade imposed by some of their neighbors, they continued to process and ship at the highest rates to keep supplying LNG to all of their customers around the world, helping to calm world markets during a very vulnerable period.

“Baroudi, left, with Mitsotakis at the 2019 EUArab World Summit in Athens, before the latter became Greece’s prime minister. According to Baroudi, Mitsotakis has done much to speed his country’s recovery.”

Finally, the role played by Qatar and its leaders has captured the attention of the international community due to the wise policies of the Ruler of the Gulf state. His efforts have been lauded and appreciated by East and West alike, ranging from visits of goodwill by the Emir to regional countries, to forging relations based on mutual respect and cooperation. It also has been noted that visits by the Emir tend to manifest high levels of support in mediation, bringing peace, providing materials or otherwise, as and when needed.

By contrast, assistance to Ethiopia has declined in recent years. As a result, Ethiopia recently defaulted on its external debt, even though it amounts to just 25% of GDP. While the Kenya approach is not the solution – providing similar levels of support to all illiquid countries would require a tripling of MDB flows – this is clearly unacceptable.

A better approach would focus on closing the gap between short-term debt concerns and long-term investment needs, by unlocking net-positive inflows for countries facing liquidity constraints. As the FDL has proposed, an agreement among debtors, creditors, and MDBs to permit countries to reschedule debts coming due – delaying maturities by 5-10 years – would create fiscal space for climate-friendly investments, financed by MDBs.

For this liquidity bridge to work, MDBs would have to accelerate progress on implementing existing reform plans and increase funding substantially, while the IMF helps manage debt-rollover risks. Importantly, private and bilateral creditors would have to agree to the rescheduling. That is why, compared to the Debt Service Suspension Initiative that the G20 introduced in 2020, the proposal includes stronger incentives for private-sector creditors to participate, in addition to longer time horizons.

There are good reasons to believe that creditors can be convinced to join the program voluntarily. It is, after all, in their best interest to remain invested in solvent countries with strong growth prospects; no one benefits from debt crises like those that have ensnared Zambia and Sri Lanka. In any case, creditors would continue receiving interest payments, and as global interest rates fall and economic-growth prospects improve in the coming years, debtors may well be able to return to capital markets and resume repayment of the principal.

Shaping a workable blueprint along these lines is a task for upcoming international gatherings, such as the G20 summit in Brazil later this year. Logistical and financial coordination will be needed to ensure sufficient liquidity. Coordination among the IMF, the World Bank, and regional development banks will also be essential to ensure that participating debtor countries pursue investments that genuinely support green growth.

If nothing is done to help countries facing liquidity crises, the world will risk a wave of destabilizing debt defaults, and progress on the green transition will be severely undermined, with catastrophic implications for the entire world. Because promising solutions like the liquidity bridge can prevent such outcomes, they deserve broad global support.