Energy efficiency should not just be a matter of reducing energy consumption. As renewables grow pricing and profits should encourage renewable consumption. After all, renewables aren’t a problem. And greater renewables consumption means less fossil fuels.Yet consumer pricing models with a low fixed price + high variable rate are designed to discourage all consumption, warns James Bushnell of the Energy Institute at Haas. He says we must recognise that consuming energy is not, in and of itself, a bad thing. Valuable goods and services are made and enjoyed using energy. We shouldre-focus pricing to penalise the wasteful and inefficient, while encouraging the clean.

There are two duelling, strongly held, views on the definition of energy efficiency. The idea of energy efficiency, at least to economists, is to overcome market failures that can lead to people consuming energy even when the full societal costs of the energy exceed their benefits.

An alternative perspective also pervades policy circles. This perspective appears to be that people should just use less energy, period. To economists, this view is a perversion of the notion of energy efficiency. Energy efficiency should be about the efficient use of energy, not the non-use of energy.

Pricing electricity

One policy arena where these duelling views are colliding is electricity rate design. About a month ago I participated in a workshop at SMUD concerning a proposal to add a monthly fixed surcharge to homes that newly add rooftop solar. The logic behind the proposal was a familiar one to readers of the Haas blog site: many fixed utility distribution costs are recovered in variable, per kWh rates, and solar homes avoid paying for those fixed costs when they generate their own electricity but stay connected to the system. For SMUD, this is a financial concern: how to equitably recover the fixed costs of their infrastructure?

But there is a larger societal issue that gets overlooked when we focus too much on just the financial viability of a distribution utility. The larger question is: exactly what kind of behaviour do we want to discourage, or encourage, from consumers when we set electricity prices, and why?

The SMUD proposal was, not surprisingly, roundly criticised and opposed by solar trade groups. Somewhat frustrating, but not surprising, was the vocal opposition from 350.org and other environmental groups as well. My frustration stems from my belief that we have a much better chance at combating climate change if we direct our scarce resources away from rooftop solar toward more cost-effective solutions like grid-scale solar. What was surprising to me, however, was how the conversation turned to the wisdom, even the ethics, of SMUD’s general tariff structure, which has a higher monthly fixed charge, and lower variable prices, than most other California utilities.

Electricity prices: how high is too high?

The general tone of this part of the discussion was that it was socially irresponsible for SMUD to charge a lower variable price of electricity, because it would encourage people to use more electricity. The argument is often extended to support steeply rising increasing-block rate structures, such as exist in much of California, on the grounds that higher prices encourage conservation (i.e., discourage electricity use). This begs a question that I wish I had asked at the time, but didn’t. If lower electricity prices are “bad”, and by implication higher electricity prices “good”, then how high is too high?

Social marginal costs

Economists have a framework for answering this question. It is called marginal cost. Because we, as a society, are worried about climate change and other environmental costs, we should include those in marginal cost as well. That’s called social marginal cost (the cost of producing the electricity plus the external damages done by it). Ideally marginal prices would be set at social marginal cost, so that when a consumer turns on a light bulb, or charges their electric vehicle, the incremental amount they pay matches the incremental cost they impose on society.

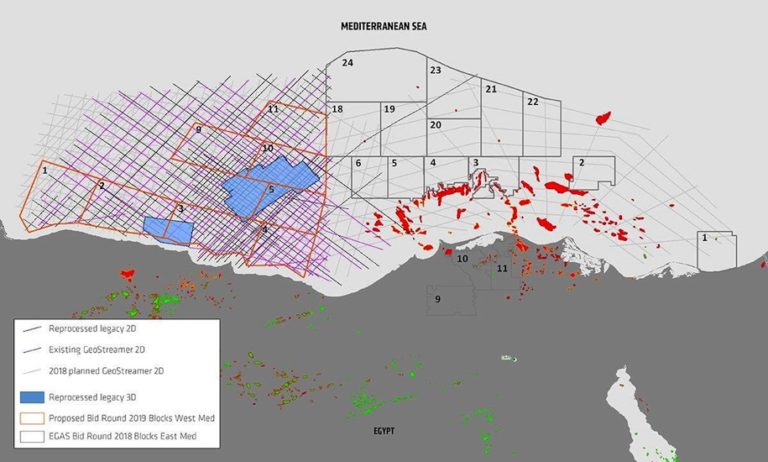

In a previous blog, Severin Borenstein talked about work we have been doing estimating the social marginal cost of electricity around the US, and comparing it to the marginal ($/kWh) price faced by residential customers. These social costs reflect the marginal wholesale cost of electricity and researchers’ estimates of the environmental costs of generation. There is a striking diversity across the US in the relationship between marginal prices and social marginal cost, but one fact that stands out is that marginal prices in California are among the highest in the country even though our marginal cost of electricity is among the cheapest and cleanest in the country.

Energy Efficiency: duelling definitions

Again, the idea of energy efficiency—at least as an economic concept—is to overcome market failures that lead to people consuming energy even when the costs exceeded their benefits. There are two types of market failures, broadly speaking: either the energy price is “wrong” or the price is right but consumers don’t respond correctly to it.

The first failure is usually linked to externalities, like climate change, whose costs may not appear in the energy price, leading consumers to consume “too much” because the price, lacking the environmental cost, is “too low.” The second failure can be attributed to a myriad of institutional breakdowns, like landlords who don’t have an incentive to invest in efficiency for tenants, or behavioural factors such as consumers misunderstanding or not wanting to spend the time understanding their electricity prices.

But a corollary to the economic view of energy efficiency is that if true social costs are low, it’s OK to consume more. In fact, it’s a bad idea, even wasteful, to devote scarce resources to reducing consumption if the costs of those investments exceed the benefits provided. This is where electricity pricing comes into the picture. If we set electricity prices well above the costs of serving customers, we are encouraging consumers to take steps to reduce electricity consumption when the electricity cost savings outweigh the investment costs to the customer, but not to society. Rational consumers will reduce their electricity consumption (or install rooftop solar) based upon these price distortions.

Indeed, this is exactly what my colleagues at UC Davis, Kevin Novan and Aaron Smith find in their 2016 paper, The Incentive to Over-invest in Energy Efficiency. They study air conditioner replacements in Sacramento and estimate that while the AC investments save about $11.50 per month in avoided social costs, they save the consumers who make the investments about $26.50 per month because of SMUD’s rate structure where marginal prices exceed marginal social cost.

Considering the fact that marginal electricity prices are more than double the marginal cost of energy (including externalities) in much of California, any behavioural reluctance on the part of consumers to invest in energy efficiency could actually improve rather than reduce total benefits. The customer’s cost-benefit test for saving money needs to be passed by a wide margin before energy efficiency makes economic sense in places like California. Unfortunately, as the above map illustrates, as a country, we are devoting funds to overcoming customer inertia in all the wrong places. Energy efficiency program expenditures are highest in states with high prices and clean electricity, and low to non-existent in the states where electricity is dirty and more expensive.

Less is more, no matter what?

One can argue with the specific numbers, but the general principle of marginal cost pricing is pretty compelling. If consumers want to consume energy and are willing to pay the societal cost to provide it, their consumption creates a benefit that economists call welfare. If prices rise well above social marginal cost, then we are inefficiently discouraging the use of electricity. Yet there are some who are not persuaded. They appear to think people should use less energy, period, regardless of whether costs are low or costs are high.

More consumption, so long as it’s renewable

The inconsistency in the “less is more, no matter what” view of energy efficiency is becoming more obvious as the grid gets cleaner and we are hoping to electrify other sectors, like transportation and home heating. The former trend means that the social marginal cost is getting cheaper, even while the total cost of providing electricity is getting more expensive (including fixed costs like renewable capacity, the transmission system, etc.). In fact, there are times and places where electricity is effectively costless. Do we really want to discourage consumption, even the charging of EVs, through high prices during times like these?

It is interesting that some opponents of rate structures like monthly fixed charges also support increased time-varying prices. Support for the latter implies a recognition that when costs are low it’s OK to encourage consumption. However, opposition to fixed charges when marginal prices are so far in excess of costs implies a rejection of the same principles of marginal cost pricing that would lead one to favour time varying prices.

The other area where the view of “less electricity is better” runs into trouble is when we consider what the alternatives to electricity consumption are. Those alternatives are increasingly gasoline or natural gas. If marginal electricity is clean and cheap, we want people to shift from gasoline to electricity to power transportation. But high electricity prices clearly undermine that transition.

So, what exactly are we trying to achieve with electricity prices? Once we deviate from the principle of marginal cost pricing, we risk making moral judgments about how other people perceive the benefits of consuming energy. Now I’m not against doing that. I quite enjoy judging other people, in fact. But it’s a wobbly foundation to base public policy upon.

As a policy community we need to come to some common understanding about what energy efficiency is and should be. This means recognising that consuming energy is not, in and of itself, a bad thing. Many fantastic goods and services are made and enjoyed using energy. What is “bad” is wasting money and polluting the environment. Energy efficiency efforts should be focused on truly wasteful, inefficient consumption. When we place the marginal price of electricity excessively high, we are throwing out the good consumption with the bad and making the achievement of our ultimate goal of a prosperous, clean-energy society harder to reach.