Why company carbon cuts should include ‘scope’ check

When a company pledges to cut its carbon emissions, how big a deal is it? That depends on what’s being counted. An oil company’s direct emissions – those from its trucks, drills and facilities – are only a sliver of the carbon released when the fuel it sells is burned, and an airport vowing to use wind power for its runway lights is making a much smaller commitment than if its promise covered the flights that take off there. As more investors take environmental factors into account, what had been a technical debate is taking on increased importance, as a matter of “scope.”

1. What does scope mean?

As the effort to boost green investment has grown, so have efforts to create metrics and standards for accounting and disclosure. Counting emissions isn’t as simple as tracking what comes out of a smokestack. Under what’s known as the Greenhouse Gas Protocol Standard, emissions are classed as Scope 1, 2 or 3. Scope 1 covers “direct emissions” – those from sources that are owned or controlled by a company, like those oil company trucks. Scope 2 covers emissions from the generation of energy the company buys, such as electricity or heat. Scope 3 is everything else: the emissions that come from the entire value chain.

2. What does that mean?

Scope 3 covers emissions from all of a company’s non-energy inputs, like steel for a drilling rig or cement for its buildings, and from all the uses to which a company’s products are put, like the fuel an oil company sells. It’s the complete supply chain, which means that for almost all companies, Scope 3 is far bigger than the other two scopes combined.

3. What’s the purpose of breaking it down this way?

To add meaning to company pledges about becoming more climate friendly, and to give investors more objective measures for evaluating how a company or sector is doing on going green. The hope is that disclosure will give the market the opportunity to reward or pressure companies depending on their performance.

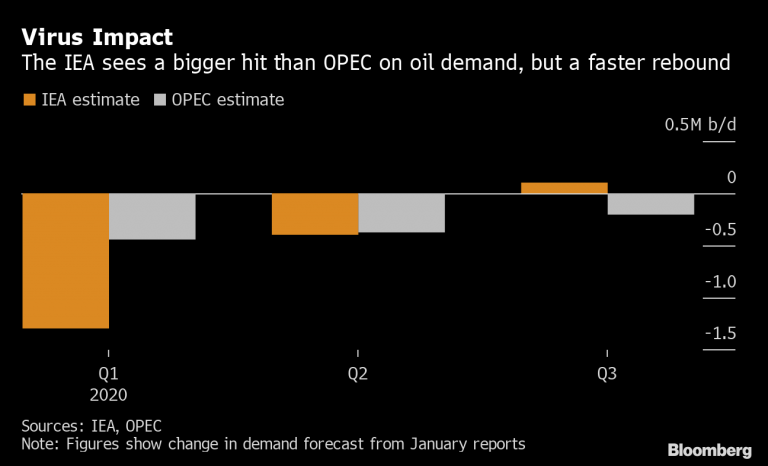

Calculating Carbon

Oil companies’ carbon footprints are mostly due to scope three emissions

4. Where did this approach come from?

The first investor to measure the carbon footprint of a portfolio may have been Henderson Global Investors in 2005, but the idea gained momentum following the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change, in which countries pledged to set specific targets for emissions cuts to slow down the threat of global warming. The Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures, an industry-led group set up that year to encourage companies to put details about their environmental risks in the public domain. It encourages investors and executives to disclose the scope 1 and scope 2 emissions of their portfolios, and scope 3 “if appropriate.” (The task force was founded and is chaired by Michael R. Bloomberg, the majority owner of Bloomberg LP, the parent company of Bloomberg News.)

5. Is it working?

To an extent. Some companies are beginning to clean up supply chains that they’ve left to their own devices for decades. They’re questioning how their raw materials are manufactured and, among other things, are moving to develop greener, cleaner ways of making steel or cement and transporting goods. Vestas Wind Systems A/S, the world’s largest maker of wind turbines, promised to eliminate all waste in the production of its machines by 2040 as part of its drive to hit carbon neutrality by the start of the next decade. Big emitters like Royal Dutch Shell Plc, BP Plc and Equinor ASA have committed to carbon-emissions targets that include Scope 3, that is, the end use of the products they sell, while Repsol SA pledged to eliminate all emissions from its operations and fuel sold to customers by 2050.

6. What kind of problems are there?

Climate disclosure is voluntary, and among the companies that are making pledges on emissions, there are no requirements about what kind of scope needs to be covered. For instance, last year National Grid Plc, the U.K.’s power network operator, unveiled a plan to hit net zero emissions by 2050, but the plan only covered Scope 1 and 2, which together made up only 18% of emissions when Scope 3 was included.

7. Can that change?

Maybe. The Science-Based Targets Initiative, a non-profit group that encourages companies to set emissions targets based on the latest available scientific pathways, has said that if any member company’s scope 3 emissions account for 40% or more of its total emissions, it should set a target covering scope 3. Companies also face growing pressure from asset owners, such as pension plans and sovereign wealth funds, as well as their employees, lawmakers and activists. Money managers from Amundi SA to BlackRock Inc have pledged to use their vast resources to combat climate change. Non-profits like CDP, a U.K.-based group, are pushing for increased transparency, working with thousands of companies around the world including Bloomberg to help them be more open and better understand their environmental impact.