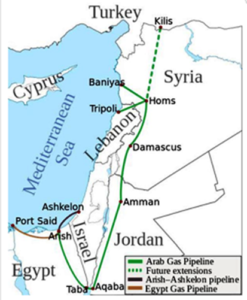

Arab Gas Pipeline

In Italy, a Sleeper Crisis for the E.U.

It is a strange development that the greatest alliance of democratic states in modern history, the European Union, has come to fear democratic votes and elections. Yet the plebiscite on a set of constitutional changes in Italy on Sunday may be a momentous day for Europe and the European Union.

Italy was a founding member of the European Economic Community and of the common currency, the euro. If Italy votes no in the referendum and then turns against Brussels and the euro, it might well spell the end of the European Union. It would also be a serious and lasting defeat for a reformist and internationalist social democracy.

Formally, the plebiscite puts to voters a set of constitutional changes that make a lot of sense. Matteo Renzi, Italy’s prime minister, proposes to reduce the power of the Senate, the upper house of Parliament. Unlike its American counterpart, the Italian Senate has not just representatives from various regions but also “lifelong” appointees and stakeholders from various lobbies.

The senators have blocked many decisions made by the Parliament in the past; because they tend to be older (minimum age of 40), they are often seen as a symbol of Italy’s “gerontocrazia.” Reducing the powers of the Senate is a key step to modernizing Italy’s political system and meeting economic challenges. In fact, a majority of the senators agreed with Mr. Renzi’s reforms, and they seemed likely to be approved in the plebiscite.

But in polls after September (before a blackout was imposed leading up to the vote), public opinion turned against Mr. Renzi and his proposals. That is largely because he has failed to deliver on his main promise to improve the economy. Italy has not yet fully recovered from the 2008 global crisis: For example, unemployment is higher than in most of the European Union, with youth unemployment hovering around 40 percent.

By these economic indicators, “la crisi,” as the Italians call it, is as deep as the depression that hit Poland and other Eastern European countries after 1989. Southern Italy now even has a lower gross domestic product per capita than Poland, adjusted for purchasing power.

Mr. Renzi made efforts to change things. He introduced job-market reforms that made it easier to hire young workers and eased some of the protections enjoyed by employees with older contracts. He has raised the retirement age modestly, a necessary step because of rising life expectancy (Italy has one of the highest life expectancies in the Western world) and to relieve the welfare state.

Mr. Renzi has also hired many young ministers instead of the old power brokers like Massimo D’Alema, the former leader of Mr. Renzi’s Democratic Party who now recommends a no vote. All in all, Mr. Renzi’s policies are reminiscent of Tony Blair’s New Labour in the 1990s or Germany’s labor-market and pension reforms under Gerhard Schröder after the turn of the millennium.

Mr. Renzi, however, is operating in a much worse global economic context. Italy cannot build on an export-driven growth model like Germany under Mr. Schröder, and it is suffering under a heavy debt burden left by Silvio Berlusconi.

And the tide has turned against reformist social democracy in Italy and elsewhere. The populists on the left and right build on the disenchantment, ire and despair of large parts of the electorate. They promise a real rupture, which Mr. Renzi’s party, part of the political establishment, cannot credibly offer.

If he loses the plebiscite and steps down, as he has vowed to do, the European Union would be badly damaged as well. Mr. Renzi is staunchly pro-European, while the populists rally against Brussels and the austerity policies of the Union. Jean-Claude Juncker, the president of the European Commission, understood this and unveiled a 315 billion euro investment plan in 2015. But it is probably too little, too late to help Mr. Renzi, even as Italy could benefit from investments in solar power and urgently needs investment in internet communication.

The union has also become increasingly unpopular because it largely left Italy alone to manage the tide of refugees and migrants from North Africa (more than 170,000 people have arrived in Italy so far in 2016). Hence, even many of Mr. Renzi’s adherents feel abandoned by the European Union.

Mr. Renzi’s foes — the left-wing populists of the Five Star Movement of Beppe Grillo, and the right-wing populists of the Northern League — fiercely attack the prime minister and the European Union. Mr. Grillo has indicated that if the plebiscite fails, he wants to hold a referendum on dropping the euro.

Brexit has set an example that a nation can vote against the advice offered by economic and political experts. Even without a plebiscite about the euro, Italy might become almost impossible to govern.

That will certainly frighten the financial markets. If the interest rates for Italy’s public debt, which at the moment stands at about 132 percent of gross domestic product, continue to rise (speculation against Italian government bonds has already started in recent weeks), it might be difficult to keep Italy in the eurozone.

If Italy, the fourth-largest economy of the European Union, rejects the euro, the common currency would be finished, and probably the Union as well. But how would the populists, once in power, act? If they have the choice between state bankruptcy and keeping the euro, they might still opt for the common currency.

The founding members of the European Economic Community reacted to the fall of the Berlin Wall and the breakdown of state socialism by establishing the more deeply integrated European Union and the euro. That worked well until the crisis of 2008.

It might be, however, that the union and the common currency were made for good times, not for bad ones.

Cyprus matters: An open letter to the new U.N. secretary-general

Your Excellency, Antonio Guterres:

The news out of Geneva is encouraging, offering hope that Cypriots might soon wake up from their decadeslong nightmare of division and hostility.

The potential of such a development – i.e. of a full and fair settlement that reunites the island nation’s ethnic Greek and Turkish communities for the first time since 1974 – reaches far beyond its own borders. As you yourself were quoted as saying Thursday, “We are facing so many situations of disasters. We badly need a symbol of hope. I strongly believe Cyprus be the symbol of hope at the beginning of 2017.”

Indeed, Cyprus matters – a lot, to many peoples, and for several reasons. The actual extent of symbolic value is notoriously difficult to determine, but the very demonstration that such a protracted conflict can be resolved through negotiations will buy credibility for diplomatic solutions wherever they are needed.

And that is not all, not by a long shot.

As you know, it has been determined beyond the shadow of a doubt that the Eastern Mediterranean contains world-class deposits of natural gas within the exclusive economic zones (EEZs) of several countries. This precious resource will not only generate revenues that allow regional governments to invest in education, health care and other social goods for their populations, but also provide Europe with greater energy security and lower costs that help restore its economic competitiveness.

Regardless of who ends up owning more or less of the deposits in question, Cyprus is destined to play a pivotal role that both accelerates the process by which benefits begin to flow and multiplies the positive impacts for producer and consumer nations alike.

Because of its physical location and geostrategic position, along with the often difficult relations among its neighbors, the island already qualifies as a powerful catalyst in several processes: as the most viable point of origin for a “Peace Pipe” that would carry the gas of several East Med countries to the European mainland and or to Turkey; as the most logical spot for a liquefied natural gas (LNG) plant whose output would reach customers in Europe and Asia by ship; and as the most convenient operational headquarters for everything from exploration and production to maintenance and telecommunications.

Of course, exploitation of this resource is inevitable to some extent. The gas is there, there is demand for it (especially from Europe, the world’s largest energy market), and there are no insurmountable obstacles to its extraction. Without a united Cyprus, however, the pace and scope of development will be substantially diminished. Cooperation with Turkey would remain difficult if not impossible, other regional players might judge it more prudent to build their own pipelines, and foreign investors would be less willing to invest in LNG and other capital-intensive facilities.

Excellency,

Just as a reunified Cyprus is a prerequisite for full and timely development of the region’s gas reserves, its rapid emergence as a regional energy hub can be the lifeblood of a new shared future for the island’s Greek and Turkish communities. The day-to-day work of reunification will continue long after the pageantry of any peace ceremony as homes and other properties are restored to original owners, displaced populations return to their towns and villages, and compensation is paid to qualified parties. The devil will remain very much in the details, patience will run short among people who have been waiting more than 40 years, and tempers will flare. With a lucrative gas sector growing up alongside this process, however, there will be both solid opportunities for intra-Cypriot cooperation and more financial resources available to smooth over the rough spots.

As you and others have recently stated, Cyprus is closer than ever to putting itself back together. Both President Nicos Anastasiades, who heads the internationally recognized Republic of Cyprus, and President Mustafa Akinci, leader of the breakaway Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, have expressed keen interest in – and even guarded optimism about – getting deal done sooner rather than later. What is more, a confluence of third-party interests, personalities and geopolitical developments is leading in the same direction. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan insists that he is committed to a settlement, Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras has made Cyprus a top priority, and both Russian and American energy companies are invested in the Eastern Med, giving them a shared interest in regional stability that figures to extend to their respective governments. In addition, the incoming U.S. secretary of state, former ExxonMobil chief Rex Tillerson, is a veteran oilman who not only understands energy economics but also has cultivated good relations with Moscow.

Excellency,

Many key players already have entered the mix, including ExxonMobil, whose consortium with Qatar Petroleum, the world’s largest LNG producer, has secured exploration rights to the most attractive morsel in Cyprus’ recent third licensing round, Block 10 of its EEZ. Rosneft, one of Russia’s top three energy companies and half-owned by the Russian government, just acquired a stake in Egypt’s massive Zohr field, directly adjacent to the Cypriot zone. Then there is another Russian giant, Soyuzneftegaz, which has been granted extensive exploration rights just to the east of Cyprus in Syrian waters.

Given Moscow’s decisive role in helping the Syrian government to battle insurgents, and the fact that its only overseas naval base lies on Syria’s coast, never has it been closer to securing the position of strength in the Eastern Med that Russian statesmen have sought for centuries. American power has long stood in the way, but now the two countries have a shared interest in the region’s stability, and Tillerson’s boss, President-elect Donald Trump, has articulated a less confrontational vision of the relationship.

The diplomatic tea leaves are hopeful too. Anastasiades recently credited the Turks with pushing for an early resumption of talks, describing the prospect of access to Cypriot gas as a key consideration in Erdogan’s calculations. Akinci has voiced his belief that 2017 “can be made a year of peace and resolution.” And the U.N.’s own envoy, former Norwegian Foreign Minister Espen Barth Eide, said both sides “recognize that the status quo is unacceptable and unsustainable, and that the current talks offer the best opportunity for a solution.”

Excellency,

The benefits of Cyprus’ returning to the world stage as a nascent energy hub would flow to peoples across the Euro-Mediterranean region and beyond. Once other countries in the Eastern Med start producing gas in quantities sufficient for export, a stable and unified Cyprus will make it easier for them to reach customers in Europe and Asia, providing enough revenues for a veritable renaissance of the regional economy; Turkey and its European neighbors would be surer of meeting their energy needs, and therefore of rejuvenating their own economies; the removal of an ever-present disagreement also would provide space for a rapprochement between Turkey and Greece; and the whole neighborhood would gain from a return to normality, helping it to attract more tourists and investors, expand trade relationships and increase cooperation on everything from academic and cultural exchanges to civil aviation and maritime search and rescue.

And on the aforementioned symbolic level, what could be more conducive to remedying the problems of the Middle East than to teach Arabs and Israelis that peace and coexistence are not zero-sum games? That peace is both its own dividend and the source of many more to come? That this formula can be applied to just about any case of ethnic, national and/or religious dispute? That the futures of individuals, families and communities can be radically improved by sharing a land you love with someone you used to hate?

A lot depends on the principals, Akinci and Anastasiades, to make this happen. Many members of their respective constituencies subscribe to rival narratives, but most are tired of division, and while cobbling together a workable deal and selling it in two separate referenda will be demanding work, the payoff figures to be almost incalculable. But ultimately it is up to Turkey to allow the Cypriots to find a solution that suits them.

Add all of this up, and the momentum for peace has never been greater. The people of Cyprus need and deserve all the help they can get to make good on this potential, as do those of other countries and societies in need of reconciliation, as well as still others who desperately need affordable and reliable energy supplies. In short, whoever we are, we help ourselves by assisting the Cypriots. That’s why Cyprus matters.

Roudi Baroudi is CEO of Energy and Environment Holding, an independent consultancy based in Doha, Qatar.

Cyprus matters: An open letter to the new U.N. secretary-general

The news out of Geneva is encouraging, offering hope that Cypriots might soon wake up from their decadeslong nightmare of division and hostility.

The potential of such a development – i.e. of a full and fair settlement that reunites the island nation’s ethnic Greek and Turkish communities for the first time since 1974 – reaches far beyond its own borders. As you yourself were quoted as saying Thursday, “We are facing so many situations of disasters. We badly need a symbol of hope. I strongly believe Cyprus be the symbol of hope at the beginning of 2017.”

Indeed, Cyprus matters – a lot, to many peoples, and for several reasons. The actual extent of symbolic value is notoriously difficult to determine, but the very demonstration that such a protracted conflict can be resolved through negotiations will buy credibility for diplomatic solutions wherever they are needed.

And that is not all, not by a long shot.

As you know, it has been determined beyond the shadow of a doubt that the Eastern Mediterranean contains world-class deposits of natural gas within the exclusive economic zones (EEZs) of several countries. This precious resource will not only generate revenues that allow regional governments to invest in education, health care and other social goods for their populations, but also provide Europe with greater energy security and lower costs that help restore its economic competitiveness.

Regardless of who ends up owning more or less of the deposits in question, Cyprus is destined to play a pivotal role that both accelerates the process by which benefits begin to flow and multiplies the positive impacts for producer and consumer nations alike.

Because of its physical location and geostrategic position, along with the often difficult relations among its neighbors, the island already qualifies as a powerful catalyst in several processes: as the most viable point of origin for a “Peace Pipe” that would carry the gas of several East Med countries to the European mainland and or to Turkey; as the most logical spot for a liquefied natural gas (LNG) plant whose output would reach customers in Europe and Asia by ship; and as the most convenient operational headquarters for everything from exploration and production to maintenance and telecommunications.

Of course, exploitation of this resource is inevitable to some extent. The gas is there, there is demand for it (especially from Europe, the world’s largest energy market), and there are no insurmountable obstacles to its extraction. Without a united Cyprus, however, the pace and scope of development will be substantially diminished. Cooperation with Turkey would remain difficult if not impossible, other regional players might judge it more prudent to build their own pipelines, and foreign investors would be less willing to invest in LNG and other capital-intensive facilities.

Excellency,

Just as a reunified Cyprus is a prerequisite for full and timely development of the region’s gas reserves, its rapid emergence as a regional energy hub can be the lifeblood of a new shared future for the island’s Greek and Turkish communities. The day-to-day work of reunification will continue long after the pageantry of any peace ceremony as homes and other properties are restored to original owners, displaced populations return to their towns and villages, and compensation is paid to qualified parties. The devil will remain very much in the details, patience will run short among people who have been waiting more than 40 years, and tempers will flare. With a lucrative gas sector growing up alongside this process, however, there will be both solid opportunities for intra-Cypriot cooperation and more financial resources available to smooth over the rough spots.

As you and others have recently stated, Cyprus is closer than ever to putting itself back together. Both President Nicos Anastasiades, who heads the internationally recognized Republic of Cyprus, and President Mustafa Akinci, leader of the breakaway Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, have expressed keen interest in – and even guarded optimism about – getting deal done sooner rather than later. What is more, a confluence of third-party interests, personalities and geopolitical developments is leading in the same direction. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan insists that he is committed to a settlement, Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras has made Cyprus a top priority, and both Russian and American energy companies are invested in the Eastern Med, giving them a shared interest in regional stability that figures to extend to their respective governments. In addition, the incoming U.S. secretary of state, former ExxonMobil chief Rex Tillerson, is a veteran oilman who not only understands energy economics but also has cultivated good relations with Moscow.

Excellency,

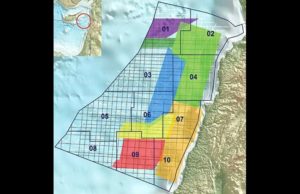

Many key players already have entered the mix, including ExxonMobil, whose consortium with Qatar Petroleum, the world’s largest LNG producer, has secured exploration rights to the most attractive morsel in Cyprus’ recent third licensing round, Block 10 of its EEZ. Rosneft, one of Russia’s top three energy companies and half-owned by the Russian government, just acquired a stake in Egypt’s massive Zohr field, directly adjacent to the Cypriot zone. Then there is another Russian giant, Soyuzneftegaz, which has been granted extensive exploration rights just to the east of Cyprus in Syrian waters.

Given Moscow’s decisive role in helping the Syrian government to battle insurgents, and the fact that its only overseas naval base lies on Syria’s coast, never has it been closer to securing the position of strength in the Eastern Med that Russian statesmen have sought for centuries. American power has long stood in the way, but now the two countries have a shared interest in the region’s stability, and Tillerson’s boss, President-elect Donald Trump, has articulated a less confrontational vision of the relationship.

The diplomatic tea leaves are hopeful too. Anastasiades recently credited the Turks with pushing for an early resumption of talks, describing the prospect of access to Cypriot gas as a key consideration in Erdogan’s calculations. Akinci has voiced his belief that 2017 “can be made a year of peace and resolution.” And the U.N.’s own envoy, former Norwegian Foreign Minister Espen Barth Eide, said both sides “recognize that the status quo is unacceptable and unsustainable, and that the current talks offer the best opportunity for a solution.”

Excellency,

The benefits of Cyprus’ returning to the world stage as a nascent energy hub would flow to peoples across the Euro-Mediterranean region and beyond. Once other countries in the Eastern Med start producing gas in quantities sufficient for export, a stable and unified Cyprus will make it easier for them to reach customers in Europe and Asia, providing enough revenues for a veritable renaissance of the regional economy; Turkey and its European neighbors would be surer of meeting their energy needs, and therefore of rejuvenating their own economies; the removal of an ever-present disagreement also would provide space for a rapprochement between Turkey and Greece; and the whole neighborhood would gain from a return to normality, helping it to attract more tourists and investors, expand trade relationships and increase cooperation on everything from academic and cultural exchanges to civil aviation and maritime search and rescue.

And on the aforementioned symbolic level, what could be more conducive to remedying the problems of the Middle East than to teach Arabs and Israelis that peace and coexistence are not zero-sum games? That peace is both its own dividend and the source of many more to come? That this formula can be applied to just about any case of ethnic, national and/or religious dispute? That the futures of individuals, families and communities can be radically improved by sharing a land you love with someone you used to hate?

A lot depends on the principals, Akinci and Anastasiades, to make this happen. Many members of their respective constituencies subscribe to rival narratives, but most are tired of division, and while cobbling together a workable deal and selling it in two separate referenda will be demanding work, the payoff figures to be almost incalculable. But ultimately it is up to Turkey to allow the Cypriots to find a solution that suits them.

Add all of this up, and the momentum for peace has never been greater. The people of Cyprus need and deserve all the help they can get to make good on this potential, as do those of other countries and societies in need of reconciliation, as well as still others who desperately need affordable and reliable energy supplies. In short, whoever we are, we help ourselves by assisting the Cypriots. That’s why Cyprus matters.

Roudi Baroudi is CEO of Energy and Environment Holding, an independent consultancy based in Doha, Qatar.

Lebanon step closer to becoming energy producer

BEIRUT: Six or seven years from now the Lebanese may able to watch from their vantage point giant platforms extracting gas from the bottom of the sea, provided that everything goes according to plan.

This sense of optimism was deepened after the Cabinet Wednesday passed the long-awaited decrees defining the blocks and specifying conditions for production and exploration tenders and contracts

Energy economist Roudi Baroudi said the passage of the two decrees was a step in the right direction.

“It’s never too late to do well. What has been done now with the passing of the two decrees is a small part to move forward. All of the oil companies that pre-qualified are still interested in exploring gas off the Lebanese coast,” Baroudi told The Daily Star.

He added that oil giants such as ExxonMobil are already operating 70 nautical miles from Lebanon, in reference to Cyprus.

It is still not clear if the Lebanese government and the Petroleum Administration will offer all of the 10 blocks off the coast for bidding.

The approval of the two decrees was seen as a crucial step after the previous cabinets shelved the issue of the gas exploration due to the deep political division in the country.

A source close to the Petroleum Administration said that newly appointed Energy and Water Minister Cezar Abi Khalil would hold a news conference Thursday to give further details about the prospect of gas exploration in the future.

“I think the minister and the Petroleum Administration will hold talks with the oil companies that won in the pre-qualification round to determine if they are still interested,” the source said.

Baroudi rejected the notion that the oil and gas glut in the world may discourage oil firms from taking part in the offshore gas licensing round in Lebanon.

“The world is still consuming double the size of gas they are producing. The prices are definitely going to go up if the consumption of gas globally remained high,” he added.

Baroudi stressed that according to a recent study, fossil fuel would remain the dominant commodity for energy production for the next 30 to 40 years. “Alternative energy such as wind mill and solar energy will only represent 20 percent of the total electricity consumption for many years to come,” he added.

The government will have a gargantuan task in persuading oil majors to participate in the next licensing round.

Former Energy Minister Gebran Bassil has said gas reserves off the Lebanese coast could potentially exceed 96 trillion cubic feet.

But companies and experts insist that it is too early to talk about the actual size of the gas reserves until drilling takes place.

However, Baroudi believes that there is strong possibility that the potential gas reserves off Lebanon’s coast may be bigger than those of Cyprus or Israel.

The other sensitive issue facing the government is the so-called disputed zone between Lebanese and Israeli territorial waters.

Lebanon has suggested that the United Nations broker a deal to demarcate this zone but Israel has rejected such a move.

International companies such as Spectrum have conducted 3-D seismic surveys of most of the coast to determine the potential size of hydrocarbon deposits.

These data were sold to the international oil companies.

A source close to the Petroleum Administration told The Daily Star just a fraction of the gas off the coast could run all of Lebanon’s power plants 24 hours a day for 25 years.

“If all the power plants in Lebanon were switched to gas, which is clean and cheap energy, then [the country] can operate all these power plants with 0.2 trillion cubic foot per year under the current energy consumption,” the source added.

He said Europe was an ideal export market once the country started pumping gas.

US OFFICIALS VISIT EAST MED TO ASSIST WITH ITS EMERGENCE AS AN ENERGY POWER

US Secretary of State John Kerry visited Lebanon last week where he met with Parliament Speaker Nabih Berri. Kerry announced to Berri that the US will be providing Lebanon with a financial aid to ease the burden created by the Syrian influx of refugees to Lebanon. Lebanon is providing sanctuary to over a million and a half Syrian refugees, a reality that is tremendously affecting Lebanon and causing authorities a major concern. The impact of the immigration is felt on a political, economic and security level. Kerry stressed on the importance of putting an end to the current political stalemate by electing a new President in the shortest delay. President Michel Suleiman’s six-year term ended last month. Lebanese politicians failed to agree on a successor since.

erri in turn expressed its hope that the U.S. will play a ‘fair and balanced role’ in mediating the Israeli-Lebanese dispute over maritime boundaries. Berri added that the U.S. could potentially benefit from such efforts as they could be involved in Lebanon’s offshore hydrocarbon explorations. Lebanon’s seabed is believed to contain substantial amounts of natural gas. Its first licensing round was postponed several times due to domestic political rivalries and is now scheduled to be opened in August 2014.

Lebanon and Israel both claim a triangular area of 850 square kilometers as their own. Direct negotiations between the two countries are inconceivable due to the fact that Lebanon and Israel are in a state of war and that Lebanon does not recognize Israel. The dispute gained importance after the discovery of substantial natural gas reserves in the Levant basin. Noble Energy discovered the Leviathan field and the Tamar field offshore Israel located respectively 130 and 80 kilometers west of Haifa with respective gross mean resources of 19 and 10 Tcf. Noble also made a successful encounter in Block 12 of Cyprus EEZ when it discovered the Aphrodite field, the third largest discovery in the deepwater Levantine Basin with a gross mean resources of 5 Tcf.

John Kerry’s visit to Lebanon follows Joe Biden’s visit to Cyprus. Biden met with the President of Cyprus Nicos Anastasiades to whom he stressed on the importance of Cyprus emerging as a net gas producer. The presence of the two senior U.S. officials in the Eastern Mediterranean Lebanon in the Eastern Mediterranean highlights the increasing importance of this region in the energy scene and Washington’s pledge to help solve the various disaccords. The Russian annexation of Crimea reminded Europe of its pressing need to diversify its geographical sources of supply. The Eastern Mediterranean could play a role in strengthening Europe’s energy security and the U.S. are investing efforts in this direction.

Greenspan admits Iraq was about oil, as deaths put at 1.2m

The man once regarded as the world’s most powerful banker has bluntly declared that the Iraq war was ‘largely’ about oil.

Appointed by Ronald Reagan in 1987 and retired last year after serving four presidents, Alan Greenspan has been the leading Republican economist for a generation and his utterings instantly moved world markets.

In his long-awaited memoir – out tomorrow in the US – Greenspan, 81, who served as chairman of the US Federal Reserve for almost two decades, writes: ‘I am saddened that it is politically inconvenient to acknowledge what everyone knows: the Iraq war is largely about oil.’

In The Age of Turbulence: Adventures in a New World, he is also crystal clear on his opinion of his last two bosses, harshly criticising George W Bush for ‘abandoning fiscal constraint’ and praising Bill Clinton’s anti-deficit policies during the Nineties as ‘an act of political courage’. He also speaks of Clinton’s sharp and ‘curious’ mind, and ‘old-fashioned’ caution about the dangers of debt.

Greenspan’s damning comments about the war come as a survey of Iraqis, which was released last week, claims that up to 1.2 million people may have died because of the conflict in Iraq – lending weight to a 2006 survey in the Lancet that reported similarly high levels.

More than one million deaths were already being suggested by anti-war campaigners, but such high counts have consistently been rejected by US and UK officials. The estimates, extrapolated from a sample of 1,461 adults around the country, were collected by a British polling agency, ORB, which asked a random selection of Iraqis how many people living in their household had died as a result of the violence rather than from natural causes.

Previous estimates gave a range between 390,000 and 940,000, the most prominent of which – collected by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and reported in the Lancet in October 2006 – suggested 654,965 deaths.

Although the household survey was carried out by a polling organisation, rather than researchers, it has again raised the spectre that the 2003 invasion has caused a far more substantial death toll than officially acknowledged.

The ORB survey follows an earlier report by the organisation which suggested that one in four Iraqi adults had lost a family member to violence. The latest survey suggests that in Baghdad that number is as high as one in two. If true, these latest figures would suggest the death toll in Iraq now exceeds that of the Rwandan genocide in which about 800,000 died.

The Lancet survey was criticised by some experts and by George Bush and British officials. In private, however, the Ministry of Defence’s chief scientific adviser Sir Roy Anderson described it as ‘close to best practice’.

MACHREK: UNE ENERGIE REGIONALE INTERCONNECTEE

II est maintenant confirme que nous aurons un reseau electrique regional pour relier ensembles plusieurs pays du Moyen-Orient. Sera-t-il realise dans un avenir proche? Le Liban y sera-t-il inclus? Quels seront ses avantages et ses consequences sur notre territoire? M. Roudi Baroudi, un consultant independant en energie, actif dans le monde Arabe et les Etats-Unis explique:

Le reseau electrique regional comprend-il cinq ou six pays et comment sera-t-il execute ?

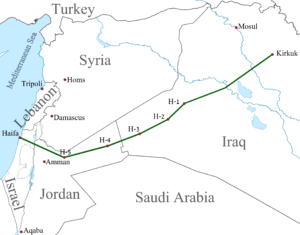

“A present, six pays, et non plus cinq sont deja relies ensembles (l’Irak, le Kowei’t, la Jordanie, la Syrie, la Turquie et le Liban). Ces connections electriques <latent du debut des annees 70 lorsque la Syrie et le Liban ainsi que la Syrie et la Jordanie ont ete connectes grace a un systeme de 66KV. II s’en est suivi, a la fin des annees 80, un lien Egypte – Jordanie avec une ligne aerienne de 400 kW.

Des le debut des annees 90, des plans et plusieurs reunions des Ministres arabes de l’electricite ont mene a bonne fin un nouveau Plan Directeur reliant la Syrie a la Jordanie par une ligne de 400 kW et la Syrie a l’Irak avec egalement une ligne de 400 kW aussi bien que l’Irak a la Turquie et la Syrie a la Turquie. Les travaux pour etablir un lien libanais allant de Ksara a la sous-station de Dimas (Syrie) grace a deux lignes aeriennes de 400kW est en nette progression.

Je confirme que ce projet est d’un grand intent pour notre utilite nationale l’EDL et, ii est de plus avantageux pour le Tresor. D’apres Jes demieres statistiques le reseau regional ETISTL aura une capacite disponible de 2500 a 3000 MW ce qui pourrait representer un cofit de 1.2 a 1.6 milliard de $ US. Les etats membres de ce reseau interconnecte n’ont pas a engager et a investir dans des projets intensifs et cofiteux. Ils pourraient utiliser leurs reserves communes de MW a travers ce reseau. Cela sera bien sfir ajoute aux autres avantages importants relevant de l’entretien periodique des equipements”.

Quel est le· statut du reseau electrique regional compare au processus du plan regional pour le gaz? “Different de l’electricite, le gaz ne doit pas etre consomme immediatement; ii peut etre entrepose pendant longtemps et etre consomme quand on en a besoin. Cela reduit les avantages de transporter le gaz a travers des canalisations parce que d’autres modes de transport et de stockage sont possibles. Les veritables benefices resident dans les differences de cofits, la source d’approvisionnement etant un facteur determinant.

D’un autre cote, le transport du gaz par canalisations est plus fiable. Quant a notre region, helas, ni l’Est de la Mediterranee, ni le Moyen-Orient ne sont encore desservis par un reseau National International. Des canalisations multinationales traversant les differents pays n’existent pas non plus a ce stade. Je pense cependant, que tout comme le reseau d’interconnexion de l’electricite qui a commence en 82 dans les pays du GCC, et plus precisement a Doha, celui des regions du Machrek et du Maghreb qui est encore en voie de realisation, prendra presque deux decennies avant d’etre acheve. Je n’y vois aucun probleme et je suis sfir que dans 5 a 10 ans, les canalisations de gaz

US OFFICIALS VISIT EAST MED TO ASSIST WITH ITS EMERGENCE AS AN ENERGY POWER

US Secretary of State John Kerry visited Lebanon last week where he met with Parliament Speaker Nabih Berri. Kerry announced to Berri that the US will be providing Lebanon with a financial aid to ease the burden created by the Syrian influx of refugees to Lebanon. Lebanon is providing sanctuary to over a million and a half Syrian refugees, a reality that is tremendously affecting Lebanon and causing authorities a major concern.

The impact of the immigration is felt on a political, economic and security level. Kerry stressed on the importance of putting an end to the current political stalemate by electing a new President in the shortest delay. President Michel Suleiman’s six-year term ended last month. Lebanese politicians failed to agree on a successor since. Berri in turn expressed its hope that the U.S. will play a ‘fair and balanced role’ in mediating the Israeli-Lebanese dispute over maritime boundaries. Berri added that the U.S. could potentially benefit from such efforts as they could be involved in Lebanon’s offshore hydrocarbon explorations. Lebanon’s seabed is believed to contain substantial amounts of natural gas.

Its first licensing round was postponed several times due to domestic political rivalries and is now scheduled to be opened inAugust 2014. Lebanon and Israel both claim a triangular area of 850 square kilometers as their own. Direct negotiations between the two countries are inconceivable due to the fact that Lebanon and Israel are in a state of war and that Lebanon does not recognize Israel.

The dispute gained importance after the discovery of substantial natural gas reserves in the Levant basin. Noble Energy discovered the Leviathan field and the Tamar field offshore Israel located respectively 130 and 80 kilometers west of Haifa with respective gross mean resources of 19 and 10 Tcf. Noble also made a successful encounter in Block 12 of Cyprus EEZ when it discovered the Aphrodite field, the third largest discovery in the deepwater Levantine Basin with a gross mean resources of 5 Tcf. John Kerry’s visit to Lebanon follows Joe Biden’s visit to Cyprus.

Biden met with the President of Cyprus Nicos Anastasiades to whom he stressed on the importance of Cyprus emerging as a net gas producer. The presence of the two senior U.S. officials in the Eastern Mediterranean Lebanon in the Eastern Mediterranean highlights the increasing importance of this region in the energy scene and Washington’s pledge to help solve the various disaccords. The Russian annexation of Crimea reminded Europe of its pressing need to diversify its geographical sources of supply. The Eastern Mediterranean could play a role in strengthening Europe’s energy security and the U.S. are investing efforts in this direction