AGENDA

THURSDAY | February 15

11.30 Participants Arrival – Registration

12.00 WELCOME REMARKS: Achilles Tsaltas, Vice President, International Conferences, The New York Times

12.10 OPENING SPEECH: George Stathakis, Minister of Energy and Environment, Hellenic Republic

12.30 REMARKS: Konstantinos Skrekas, MP – New Democracy Party, Head of Energy and Environment Sector,

- Minister of Development and Competitiveness, Hellenic Republic

12.40 REMARKS: Prof. Yannis Maniatis, MP, Democratic Coalition, f. Minister of Environment, Energy & Climate Change

Introduction & Chair: Symeon Tsomokos, Founder & Chairman, Delphi Economic Forum

12.50 Panel 1: The Global Geopolitical Parameters

- Diversification of energy sources to bring about energy independence for the region

- The impact of Brexit on EU Security & Energy Policy

Kate Smith, British Ambassador to the Hellenic Republic

Steven Bitner, Economic Counselor, U.S. Embassy, Athens

Energy sector as a leveraging tool despite geopolitical challenges

Nabil Fahmy, Dean, School of Global Affairs & Public Policy, American University of Cairo, f. Minister of Foreign Affairs, Egypt

Defne Sadiklar-Arslan, Executive Director, Atlantic Council Turkey

Introduction & Chair: Athanasios Ellis, Editor in Chief, Kathimerini English Edition

13.45 Networking Break – Light Lunch

14.30 Panel 2: Strategic Privatization Opportunities in the Energy Sector

Laurent-Charles Thery, Director for International Development, GRTgaz

George Longos, Managing Partner, Alantra

Introduction & Chair: Achilleas Topas, Journalist, SKAI Media Group Co-hosted by

14.50 Panel 3: Completing the Midstream Puzzle: Exporting Gas from the Eastern Med and the Caspian Sea

- Progress report on IGB and the dynamics of a second LNG imports facility in Alexandroupolis

- TAP: Progress Report and Phase 2

- The feasibility of the East Med Gas Pipeline

- The LNG export option

The View from Greece

Dimitrios-Evangelos Tzortzis, CEO, Public Gas Corporation – DEPA, Greece

Sotiris Nikas, President & CEO, Hellenic Gas Transmission System Operator – DESFA, Greece

Panayotis Kanellopoulos, Managing Director, M&M Gas S.A., Greece

The View from the Region

Ron Adam, Ambassador, Special Envoy on Energy, OECD coordinator, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Israel

Katerina Papalexandri, Country Manager Greece, TAP

Albert Nahas, Vice President, International Affairs, Tellurian Inc., U.S.A.

Dr. Theodore Tsakiris, Assistant Professor, Geopolitics & Hydrocarbons, University of Nicosia, Cyprus & Scientific Adviser Athens Energy Forum

Introduction & Chair: Alex Lagakos, Founding Chairman, Greek Energy Forum| Member, Sustainable Energy Committee

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe

16.00 Networking Break

16.30 Panel 4: The Domestic and Regional Electricity Market Dynamics

ADMIE: The day after the ownership unbundling

Manousos Manousakis, Chairman and CEO, Transmission System Planning Department, IPTO S.A., Greece

- The continuous need for complete market liberalization

- Progress report on the Inter-connectivity between the Islands and Mainland Greece

Prof. Nikos Chatziargyriou, Chairman & CEO, Hellenic Electricity Distribution Network Operator S.A.- HEDNO, Greece

Stavros Goutsos, Deputy CEO, Public Power Corporation, Greece

Dinos Benroubi, General Manager Electric Power Business Unit, MYTILINEOS, Greece

Introduction & Chair: Dr. Athanassios S. Dagoumas, Assistant Professor in Energy and Resource Economics, University of Piraeus

17.15 End of the 1st Day of the Forum Co-hosted by

FRIDAY | February 16

09.30 Arrival of Delegates – Coffee/Tea

10.00 KEYNOTE SPEECH: Dr. Stelios Himonas, Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Energy, Commerce, Industry and Tourism, Cyprus

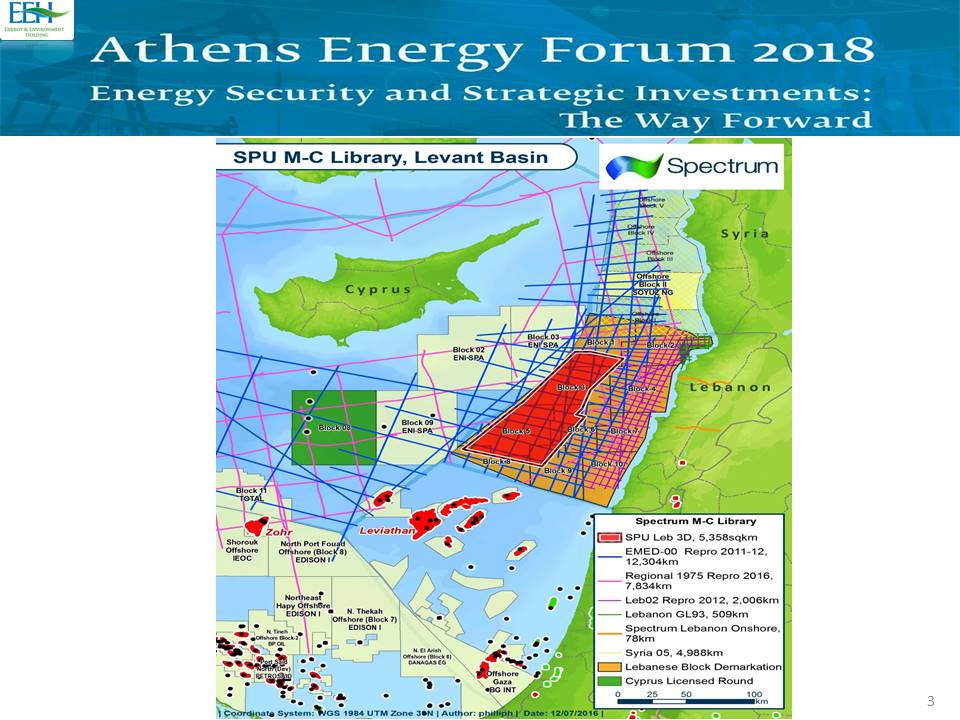

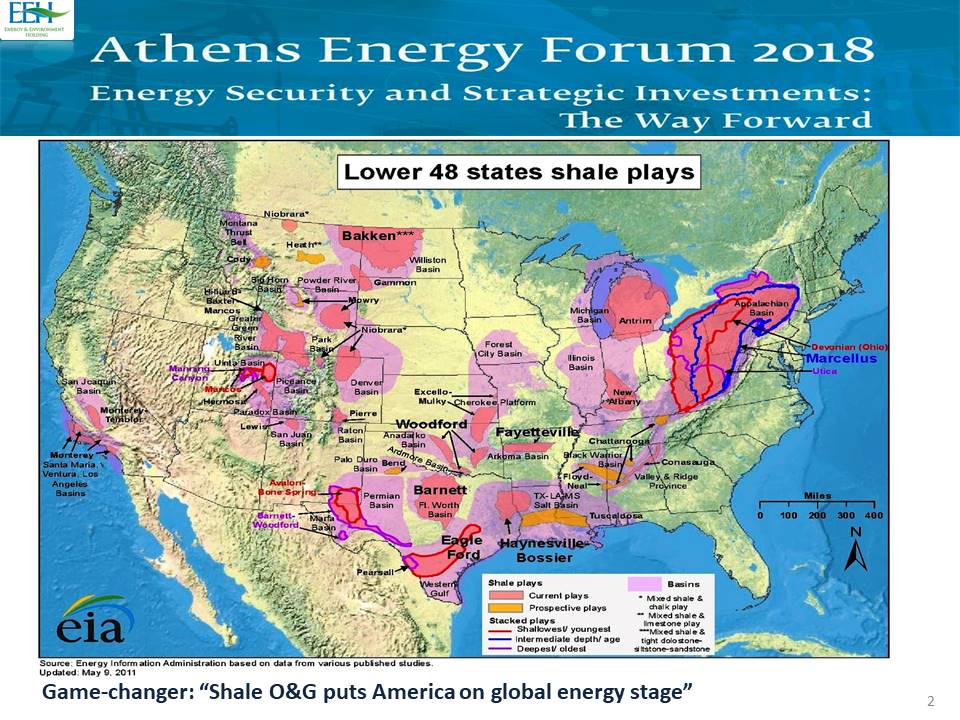

10.15 Panel 5: Regional Upstream Developments: Political, Regulatory and Economic Challenges

- The results of Cyprus’ Third Licensing Round and the Onisiphoros Discovery

- Future exploration prospects in Egypt and Israel and Lebanon’s untapped potential

- The entry of Exxon and Total in the Greek Upstream market

- Lebanon – The award of 2 offshore Blocks to TOTAL / ENI / Novatek

The national perspective

Yannis Bassias, President & CEO, Hellenic Hydrocarbons Resources Management S.A., Greece

Yannis Grigoriou, General Manager Exploration & Production of Hydrocarbons, Hellenic Petroleum SA

The regional perspective

Dr. Constantinos Hadjistassou, Ass. Professor, School of Sciences & Engineering, University of Nicosia

Bernard Clement, Vice President for Caspian and Southern Europe, Total E&P, France

Roudi Baroudi, CEO, Energy & Environment Holding, Qatar

Introduction & Chair: Dr. Theodore Tsakiris, Assistant Professor, Geopolitics & Hydrocarbons, University of Nicosia, Cyprus &

Scientific Adviser Athens Energy Forum

11.15 Networking Break

11.45 Panel 6: Sustainable development – climate change and energy

- Making energy technologies cleaner

- Responsible steps to cut carbon pollution

- Winning the global race for clean energy innovation

The evolving policy framework

Dr. Dionysia Avgerinopoulou, f. Chairman of the Standing Committee for the Environment of the Hellenic Parliament

Konstantinos Xifaras, Secretary General, World Energy Council, Hellenic National Committee

A focus on cleaner and alternative fuels

Dr. Spyros Kiartzis, Manager New Technologies & Alternative Energy Sources, Hellenic Petroleum S.A.

Dionissis Christodoulopoulos, Managing Director, MAN Diesel & Turbo Hellas Ltd, Greece

Introduction & Chair: Zoi Vrontisi, Chairwoman, National Center for the Environment & Sustainable Development Co-hosted by

12.30 Panel 7: RES, Energy Efficiency and Technological Innovation

- RES as a means of energy security

- Energy efficiency technologies as a new area for growth

- Overcoming regulatory hurdles for RES development

Harris Damaskos, Associate, EBRD

Professor Xenophon E. Verykios, Managing Director, Helbio Hydrogen & Energy Systems, Greece

Zisimos Daniil Mantas, Chief Business Development Officer, Eunice Energy Group, Greece

Introduction & Chair: Miltos Aslanoglou, Energy Regulation Expert, Greece

13.00 End of Forum