Royal Dutch Shell’s profits soared to a four-year high in the third quarter, boosted by rising oil and gas prices as the company accelerated its giant $25bn share buyback programme.

Although the $5.6bn quarterly profit slightly missed forecasts for a fourth quarter, investors took heart from a nearly 60% rise in Shell’s cash generation to $12.1bn, as deep cost savings in recent years filtered through.

Excluding one-off charges, cashflow was the highest in 10 years at $14.7bn, the company said yesterday.

“Good operational delivery across all Shell businesses produced one of our strongest-ever quarters,” chief executive Ben van Beurden said in a statement.

The Anglo-Dutch company launched a three-year $25bn share buyback programme in July, making good on a promise to boost shareholder returns following the 2016 acquisition of BG Group, in a show of confidence in its cash generation and profit growth outlook.

Shell said it completed the first tranche of buybacks in October for $2bn and was launching a second tranche yesterday of up to $2.5bn by January 28.

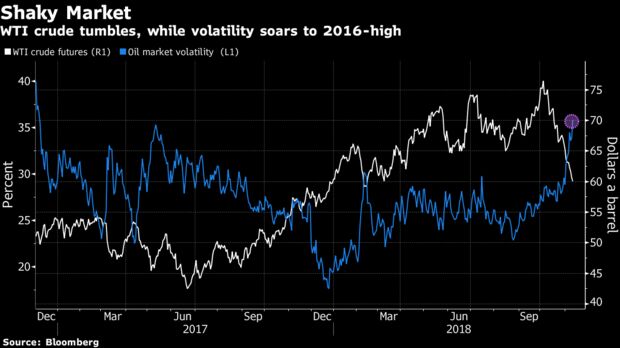

This year’s sharp rise in oil prices to a four-year high of around $85 a barrel has boosted revenues for oil and gas companies.

Shell’s net income attributable to shareholders in the quarter, based on a current cost of supplies (CCS) and excluding identified items, rose 39% to $5.624bn from a year ago.

That compared with $4.691bn in the second quarter, and a company-provided analysts’ consensus of $5.766bn.

Profits benefited from stronger oil and gas prices as well as bigger contributions from trading operations, though that was offset by weaker refining margins, tax and currency exchange effects.

Chief financial officer Jessica Uhl said Shell will stick to its $25 to $30bn capital expenditure plans in the coming years despite rising waging and services costs.

Debt levels remained stubbornly high.

Shell’s debt ratio versus company capitalisation, known as gearing, declined to 23.1% in the quarter from 23.6% at the end of June.

Oil and gas production in the quarter fell 2% from a year earlier to 3.596mn barrels of oil equivalent.

Output was expected to rise in the fourth quarter due to lower maintenance, Shell said.

Credit Suisse

Credit Suisse defended its global markets trading arm yesterday, even as losses at the division took the shine off a jump in quarterly profit as the bank wraps up a three-year revamp under chief executive Tidjane Thiam.

The unit, the focus of Thiam’s cuts and a source of billions of dollars of losses over years, still has an important role to play after the restructuring to focus on managing billionaire’s wealth and scale back investment banking, Thiam said.

Third-quarter group net income jumped 74% to 424mn Swiss francs ($422mn), helped by the ongoing wind-down of its so-called Strategic Resolution Unit — a home for assets that have been a drag on the bank’s past performance.

But that missed analysts’ average estimate of 449mn francs in a Reuters poll.

Credit Suisse said a $250mn cut to funding costs coupled with investments into its equities business should help the division raise returns next year.

ROTE was 6.3% in the first nine months of 2018.

Spotify

Spotify sent its shares tumbling as much as 10% yesterday after the world’s most popular paid music streaming service said it would continue to sacrifice profit margins to generate future growth.

The Swedish company came close to making its first-ever operating profit in the third quarter, years ahead of schedule, which the company said was because it had not been spending heavily enough to hire more engineers.

Spotify reported an operating loss of €6mn after previously guiding investors to expect losses between €10-90mn.

The company tightened its expectations for full-year 2018 monthly active listeners to between 199mn to 206mn users.

Analysts, on average, had been predicting 208mn users by the end of the year.

Monthly subscribers, which deliver 90% of revenue, rose to 87mn, up from 83mn in the second quarter ending June, it said.

The latest results matched the average forecast in a Thomson Reuters analyst poll.

Total users rose to 191mn, including free, advertising-supported listeners.

The New York Times

The New York Times said yesterday that digital subscriptions topped three million in the past quarter, keeping the prestigious daily profitable in a difficult environment for the news media.

With a gain of 203,000 online-only subscribers in the third quarter, the newspaper is now getting nearly two-thirds of its revenue from subscriptions, helping offset weakness in advertising and print circulation.

The Times posted a net profit of $24.9mn in the quarter, down from $36mn in the same period a year ago, as total revenues rose eight% to $417mn.

While its profits are modest, the Times has been among the most successful legacy news organizations navigating the transition to digital news amid sharp declines in print readership.

The quarterly update showed a 7% year-on-year increase in advertising, led by digital.

But ad revenues for the first nine months of the year are down 2.5% and the company said it expects flat advertising revenues in the fourth quarter.

According to the Times, revenue improved in part due to an agreement with Long Island daily Newsday to print and transport its publications, and the renting of four additional floors in the New York headquarters.

Teva Pharmaceutical

Teva Pharmaceutical Industries raised its 2018 earnings outlook, said it was seeing “a very strong launch” for its long-awaited migraine treatment Ajovy and expects to launch generic EpiPen in the fourth quarter.

Teva raised its full-year forecast for adjusted EPS to $2.80-$2.95, from a previous estimate of $2.55-$2.80 and its shares were 8.5% higher in early US trading.

The company also said it was on track with plans to reduce its workforce by 14,000, having let over 9,000 employees go so far.

Net debt decreased by $800mn to $27.6bn.

Teva said it earned 68 cents per share excluding one-time items in the July-September period, down from $1a year earlier.

Analysts had forecast Teva would earn 54 cents a share ex-items on revenue of $4.53bn, according to I/B/E/S data from Refinitiv.

Teva confirmed its revenue fell 19% to $4.53bn due to generic competition to its multiple sclerosis drug Copaxone, price erosion in its US generics business and a loss of revenue from the divestment of some of its products and the discontinuation of some activities.

Indivior

Embattled drug maker Indivior said yesterday the hit to revenue this year from a cheap copy of its top-selling opium addiction drug would be less than feared, as cost cutting helped it to deliver a 22% rise in quarterly profit.

Indivior has been battling the introduction of a cheaper generic version of its film-based opioid addiction treatment Suboxone, and has also faced distribution challenges with its new injectable opioid addiction drug, Sublocade.

Third-quarter adjusted net income rose to $58mn, ahead of analysts’ average forecast of $49mn, according to Jefferies.

Revenue came in at $245mn, down 11% from a year earlier, but ahead of the average forecast by 3%.

Banco Bradesco

Bradesco chief executive Octavio de Lazari said yesterday that the bank, Brazil’s second-largest lender, sees the possibility of lower default ratios and higher profitability in the coming quarters.

Recurring net income rose to 5.47bn reais ($1.47bn) in the quarter, from 4.81bn reais a year ago, the bank said in a securities filing.

Bradesco said that loan-loss provisions were 3.512bn reais in the third quarter, 23.3% lower year on year, amid a gradual recovery in Brazil’s economy.

In July, Bradesco lowered its year-end target for loan-loss provisions from 16bn to 19bn reais to 13bn to 16bn reais.

Bradesco’s loan book reached 523.5bn reais, up 1.5% in the quarter, helped mostly by retail banking.

In the last 12 months, loan book growth reached 7.5%, above the top of its 2018 target range of 3% to 7%. Lazari also said that the pace of loan book growth is expected to rise next year but avoided specifics.

ING

Top Dutch bank ING posted yesterday a 43.6% year-on-year drop in net profit for the third quarter, blamed on a multimillion-euro settlement with Dutch authorities in a money laundering probe.

Net earnings fell to €776mn ($883mn), in large part to the €775mn the Amsterdam-based lender said in September it paid to settle a criminal investigation into money laundering which found that ING had failed to ensure its accounts were not misused.

The amount included a €675mn fine and a reimbursement of €100mn which ING underspent on staffing to prevent money laundering.

“The third quarter of 2018 for ING was deeply marked by the settlement agreement with the Dutch public prosecution service,” chief executive Ralph Hamers said.

The scandal saw ING axe its chief financial officer Koos Timmermans after a two-year probe by Dutch authorities that found many white-collar crime suspects held accounts at the bank.

The case threatened to seriously damage ING’s reputation and triggered calls for the resignation of its directors.

But the dispute has not deterred customers, with ING saying it expanded its client base by 200,000 in the third quarter.

The bank now has 38mn retail customers world-wide.

Revenue was up by 6.5% to 2.12bn euros year-on-year “driven by continued growth in loans with strong margins”, tight cost control and continued low-risk costs, although these were higher than in 2017, ING said.

ING employs more than 52,000 people in 40 countries around the world.

ArcelorMittal

ArcelorMittal, the world’s largest steelmaker, expects its financial results to improve in the coming months as global economic growth drives demand and US tariffs lead to higher prices for the metal.

Arcelor reported a 42% year-on-year increase in third-quarter core profit (EBITDA) to $2.73bn, roughly in-line with analyst expectations, while sales rose 5% to $18.5bn.

Steel tariffs worked to Arcelor’s advantage in the third quarter, as 5% higher prices offset an equally large decline in steel shipments in the North American region, as the US market weakened.

Total shipments of steel also fell 5% in the July-September period, due to supply problems stemming from a disruptive power outage in France and a furnace blast in Poland.

The company plans to invest €2.4bn ($2.7bn) in its newest asset, to increase Ilva’s production and to make the plant more sustainable.

Meanwhile, asset sales demanded by the European Commission as a precondition for approving the takeover led to a $500mn impairment in the third quarter, Arcelor said.

This drove down the group’s net result by 25% to $0.9bn.

The company’s net debt remained stable at $10.5bn in the third quarter, as $1.7bn was invested in working capital.

Novo Nordisk

Novo Nordisk, the world’s top maker of diabetes drugs, reported encouraging sales of its main growth drivers yesterday as it announced more job cuts amid a restructuring to cope with intensifying pricing pressure in the US.

Novo said it had expanded its share buyback programme by 1bn crowns to 15bn crowns and free cash flow this year is now seen at 29-33bn crowns from a previous guidance of 27-32bn crowns.

Third-quarter operating profit totalled 11.81bn crowns, below an average forecast of 11.93bn crowns in a Reuters poll of analysts.

Danske Bank

Danske Bank pretax profit dropped 42% year on year in the third quarter to 3.59bn Danish crowns ($547mn), missing the 3.72bn that was expected by analysts in a Reuters poll.

The result was dented by a 1.5bn crown donation, which the bank decided in July to give to initiatives to combat financial crime after a money laundering scandal at its Estonian branch.

If any income from the non-resident portfolio becomes subject to confiscation by relevant authorities, any such confiscation would be deducted from the amount to be donated, the bank said yesterday.

The scandal involves €200bn ($230bn) in payments through Danske’s Estonian branch between 2007 and 2015, many of which Denmark’s largest bank said in a report in September it regards as suspicious.

When it published the report in September Danske Bank cut its forecast for 2018 net profit to 16bn to 17bn Danish crowns, from a previous forecast of 18bn to 20bn crowns due to the donation.

The bank kept that forecast yesterday.

The scandal has led the bank’s former chief executive Thomas Borgen to resign and almost halved Danske Bank share price since February.

Sberbank

Russia’s largest lender Sberbank has posted a record-high quarterly profit yesterday for the turbulent third quarter, beating market expectations although the pace of profit growth declined.

Sberbank said it made 228.1bn roubles in net profit in the period July-September, posting a 1.8% rise year-on-year after a 16% jump in its profit the previous quarter.

Analysts polled by Reuters had on average expected Sberbank to post 204.3bn roubles in the third-quarter net profit.

Sberbank has outperformed rivals during Russia’s economic crisis and has been reporting record quarterly profit for several quarters in a row.

In the first nine months of 2018, Sberbank said its net profit totalled 665.5bn roubles under the International Financial Reporting Standards.

BT

British broadband company BT reported a better-than-expected 2% rise in first-half earnings and nudged its guidance for the full year higher, as outgoing chief executive Gavin Patterson said the group’s recovery plan was delivering.

BT, the market leader in both broadband and mobile, said the rise in profit was mainly driven by more sales of high-end smartphones and cost savings across the business.

The group posted adjusted core earnings of £3.68bn ($4.74bn) and said it expected earnings for the year to be at the upper end of its £7.3-7.4bn range.

Adjusted revenue slipped 1% to £11.62bn as regulated price reductions in its broadband network, which serves other operators as well as BT, and declines in its enterprise businesses offset growth in consumer.

National Australia Bank

National Australia Bank reported yesterday a 14.2% drop in cash earnings to A$5.7bn (US$4.0bn) due to restructuring charges and the costs of repaying customers impacted by bank misconduct.

NAB’s profit in the year to September 30 was still up five% to AU$5.55bn despite what chief executive Andrew Thorburn called a “challenging year”.

“Our transformation is on track and benefits are emerging as we become simpler and faster,” he said, pointing to growth in both housing and business lending.

Sibanye-Stillwater

South African miner Sibanye-Stillwater’s core profit plunged 40% in the third quarter, it said yesterday, after production at its domestic gold mining operations was hit by incidents that have caused 24 deaths this year.

Sibanye, which also produces platinum, said adjusted earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA) totalled 1.6bn rand ($109mn) in the three months ended September, down from 2.7bn rand a year earlier.

As well as production cuts, the miner also had to defer some US sales in September until October at the request of a client, a precious metals refiner, it said.

The miner said comparable gold production from its South Africa operations fell 24% to 284,600 ounces for the quarter after rehabilitation of seismically affected production areas and the suspension of underground mining at its Cooke operations.

The firm revised its 2018 guidance for its local gold operations down to between 1.13mn ounces and 1.16mn ounces, from its previous guidance of between 1.17mn ounces and 1.21mn ounces.

Platinum group metals (PGM) production from the group’s South African operations fell to 305,227 ounces in the third quarter, from 306,184 ounces a year earlier, while output at its U.S operations rose 3% to 139,178 ounces compared with the year ago period.

Orsted

Danish energy group Orsted posted third-quarter profit well above analyst expectations yesterday and lifted its outlook for the year, in part thanks to the contribution from new offshore wind projects.

Orsted now expects EBITDA for the year excluding new partnership deals at 13bn to 14bn Danish crowns, up from 12.5bn to 13.5bn previously guided.

Orsted is rebranding itself as a renewable energy firm after it sold its oil and gas unit to Ineos last year, courting investors interested in green investments which have seen a boost amid policies to protect the climate.

The firm, formerly known as DONG Energy, reported earnings before interest, taxation, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA) of 2.23bn Danish crowns ($340mn), compared with 1.85bn crowns forecast in a Reuters analyst survey.

Including profits from the Hornsea 1 partnership in the UK, Orsted said it still expects EBITDA for the year to be “significantly higher” than the 22.5bn achieved in 2017.

Analysts on average expect EBITDA of 27.3bn for 2018.

The company’ power generation increased 12% between July and September compared to a year earlier.

The company also said it submitted a bid in a clean energy auction in Connecticut in September and expects to receive the outcome of the auction before the end of the year.

The bid comes after it said in August it would acquire US wind farm developer Lincoln Clean Energy.

“During the third quarter we have secured a very strong and long-term growth platform in the American market,” Poulsen said in a statement.

General Motors

General Motors profits eclipsed expectations in the latest quarter, despite the impact of tariffs and slipping sales volume, as the company unveiled a plan on Wednesday to cut jobs and reduce costs.

The company reported better-than-expected third-quarter earnings even as it sold fewer vehicles in both North America and China.

Strong pricing in those markets allowed the company to offset the hit from trade tariffs and the burden of the strong dollar in South American markets and report profits that topped Wall Street forecasts by a wide margin.

Earnings for the quarter ending September 30 were $2.5bn — up from a loss of $3bn in the year-ago period when results were hit by a one-time accounting charge.

That translated into $1.87 per share, compared with Wall Street expectations for $1.25 per share.

Revenues rose 6.4% to $35.8bn.

GM said it experienced $400mn in higher costs due to US tariffs on steel and aluminium but that strong pricing and cost cuts had offset the hit.

GM sold fewer cars in North America than in the comparable period in the prior year, falling nearly 10% to 833,712 units, but benefited from a higher pricing following a number of truck and sport utility vehicle launches.

The Silverado pickup truck is currently selling more than 30% above forecast, Barra said, adding that the company will have several new truck trims in dealerships within two weeks.

Sales volumes also declined in China, falling by 14.9% to 835,934 vehicles compared with the prior year.

But again, strong pricing boosted results, permitting GM to score record equity profits from China during the quarter.

GM has enjoyed especially strong sales of its Cadillac brand, which is up 20% amid robust demand in luxury and premium segments.

Executives said recent economic weakness has dented sales in smaller “Tier 3-5” Chinese markets.

These smaller cities “tend to be our less profitable part of the market,” chief financial officer Dhivya Surgadevara said.

In contrast, larger markets saw less of a drop and the luxury market “is actually up year over year.”